Rubin Observatory will inspire a new era in space missions without ever leaving the ground

Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s detailed, big-picture view of our Solar System and ability to quickly detect and track moving objects will provide a gold mine of data to benefit space mission planning and preparation.

LSST Camera

Vera C. Rubin Observatory will search wide and deep into the cosmos for signs of dark matter and dark energy and yield new insights into our own galaxy and solar system. SLAC built Rubin's LSST Camera (above), the largest camera ever built for astrophysics. SLAC will also host Rubin's U.S. Data Facility and co-lead the observatory's operations along with NSF's NOIRLab. (Image Credit: Jacqueline Ramseyer Orrell/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)

Vera C. Rubin Observatory will help scientists identify intriguing targets to prioritize for future space missions by detecting millions of new Solar System objects, and by revealing — in more detail than we’ve ever seen — the broader context in which these objects exist. Additionally, Rubin may alert scientists to the existence of objects like asteroids, comets, or visiting interstellar objects in time to determine their trajectories and prepare space missions to study them.

We live in a very exciting time for Solar System exploration, with recent headlines announcing new results from space missions like NASA’s OSIRIS-REx, Lucy, and Psyche, and ESA’s Juice. These uncrewed spacecraft have been visiting our cosmic neighbors and returning close-up images, detailed information, and even extraterrestrial rocks and dust to Earth. But space missions are only possible with extensive research, preparation, and guidance by scientists here on Earth — and observations from ground-based astronomical observatories are critical to this process. Vera C. Rubin Observatory, jointly funded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF) and the US Department of Energy (DOE), will soon start producing one of the largest and most uniform astronomical data sets scientists have ever had, providing them with a treasure trove of information they can use to plan and prepare the next generation of scientifically rewarding and ambitious space missions.

Rubin Observatory is located in Chile and will begin science operations in late 2025. Rubin Observatory is a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab, which, along with SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, will cooperatively operate Rubin.

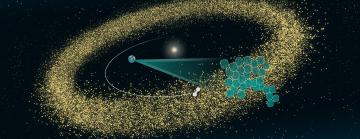

The Solar System, our cosmic backyard, is teeming with billions of small rocky and icy objects. Most formed in early times, such as near-Earth objects and Trojan asteroids, while others are distant travelers from solar systems beyond our own, known as interstellar objects.

Over the ten-year Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), Rubin Observatory will scan the entire southern hemisphere sky every few nights with an 8.4-meter, fast-moving telescope and the largest digital camera in the world, revealing millions of previously unknown Solar System objects for the very first time. Rubin Observatory’s survey is expected to potentially quintuple our current census of known objects in the Solar System, which scientists have been painstakingly building for more than 200 years.

“Nothing will come close to the depth of Rubin’s survey and the level of characterization we will get for Solar System objects,” says Siegfried Eggl, Assistant Professor at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Lead of the Inner Solar System Working Group within the Rubin/LSST Solar System Science Collaboration. “It is fascinating that we have the capability to visit interesting objects and look at them close-up. But to do that we need to know they exist, and we need to know where they are. This is what Rubin will tell us.”

While detecting millions of new individual objects, Rubin will also provide information about the Solar System’s broader landscape and reveal whole regions that contain scientifically interesting or unique objects to consider for future space missions.

“If you think of Rubin as looking at a beach, you see millions and millions of individual sand grains, that together constitute the entire beach,” says Eggl. “There might be an area of yellow sand, or volcanic black sand, and a space mission to an object in that region could investigate what makes it different. Often we don’t know what’s weird or interesting unless we know the context it’s in.”

In addition to providing astronomers and astrophysicists with the most comprehensive, big-picture view of the southern sky to date, Rubin will also alert them to changes in the night sky within 60 seconds of detecting them. This early warning system could prompt scientists to start preparing a space mission to a fast-moving target — perhaps even a visiting interstellar object, suggests Eggl. “Rubin is capable of giving us the prep time we need to launch a mission to intercept an interstellar object. That’s a synergy that’s very unique to Rubin, and unique to the time we’re living in.” In fact, such missions are already in development — the JAXA/ESA Comet Interceptormission will launch in 2029 and await the discovery (likely by Rubin) of a visitable long-period Solar System comet or interstellar object passing by the Sun for the first time.

Rubin’s detailed and frequent observations of Solar System objects and their locations could benefit space missions already in progress as well, alerting scientists to worthwhile observing opportunities near a spacecraft’s path, or within reach via a small detour. NASA’s Lucy, for example, is on a 12-year mission that Rubin is well-poised to influence. Lucy, the first space mission sent to study asteroids trapped in and around Jupiter’s orbit, has already returned valuable scientific information — and some unexpected results. And, when Rubin’s survey begins, smaller, fainter asteroids near Lucy’s future path will come into view for scientists here on Earth for the first time, potentially offering new flyby opportunities — and new scientific surprises — we can’t begin to predict.

“With our current telescopes we’ve essentially been looking at the big boulders on the beach,” says Eggl, “but Rubin will zoom in on the finer grains of sand.”

Rubin Observatory is a joint initiative of the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Department of Energy (DOE). Rubin is operated jointly by NSF’s NOIRLab and SLAC.

This article is based on a story from the Rubin Observatory.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.