Preparing for the greatest cosmic movie ever made

Now that NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s LSST Camera has been installed, what’s next?

By Gaëlle Suter

April 3, 2024

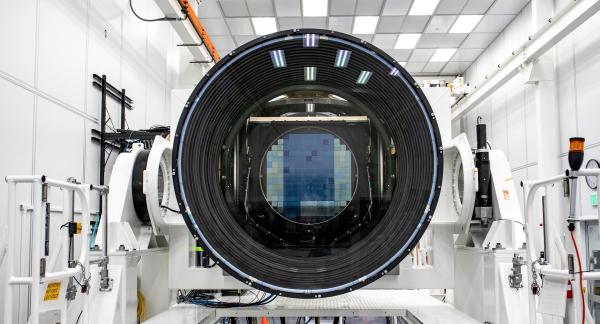

SLAC completes construction of the largest digital camera ever built for astronomy

Set in place atop a telescope in Chile, the 3,200-megapixel LSST Camera will help researchers better understand dark matter, dark energy and other mysteries of our universe.

High up on the top of Cerro Pachón in northern Chile, NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science (DOE), is nearing completion. At the heart of the facility, a pivotal moment in the project’s scientific adventure is unfolding. After more than 20 years of meticulous research and development, and weeks of testing, the LSST Camera has been successfully installed on the Simonyi Survey Telescope.

The teams breathe a collective sigh of relief. The world’s largest digital camera, built at the DOE SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory (SLAC), is now in place, and the anticipation of capturing the first images for the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) is palpable. The greatest astronomical movie ever made is about to begin.

Well, almost.

Starting up such a sophisticated camera is far more complicated than pressing a simple ‘on/off’ button. Creating the greatest astronomical film in history takes time, patience, and a commitment to precision. Every detail must be double-checked, and every system must meet its exact specifications before proceeding.

Unlike in the past stages of construction, the camera team now operates five meters (16.4 feet) above the ground, securely harnessed to a small platform that supports no more than 125 kilograms (275 pounds). Their movements are limited by the camera’s rotation and the telescope’s mirrors, positioned just inches away. What might seem like a simple hose connection becomes an entirely new challenge under these conditions.

The LSST Camera is about to undergo a series of critical steps. The first one is to create a vacuum inside the cryostat, a container designed to maintain extremely low temperatures, positioned in the middle of the camera. The cryostat houses the camera’s complex electronic systems and its mosaic of 189 charge-coupled device (CCD) science sensors. These sensors are designed to capture images of the night sky with exceptional precision, with each image made up of 3,200 megapixels.

With his hands inside the camera, working to connect the vacuum system, Stuart Marshall, camera operations scientist and staff scientist at SLAC, explains, “The vacuum is crucial to insulate the camera’s electronics from temperature changes. Once we’ve ensured a stable vacuum, we’ll activate the refrigeration system which will cool the cryostat to very low temperatures.” The electronics generate about one kilowatt of heat during operation, roughly equivalent to the output of a small electric heater. This heat must be removed from the vacuum chamber to prevent overheating. “We want the camera’s electronics to be between –20 and –5 degrees Celsius (–4 and 23 degrees Fahrenheit) to maintain a safe operating temperature. So we need to pull that heat out. And we do it by pumping a fluid at –50 degrees Celsius (–58 degrees Fahrenheit) through the cooling system.”

Meanwhile, the CCDs themselves must be cooled to –100 degrees Celsius (–148 degrees Fahrenheit). This temperature ensures optimal performance and helps prevent unwanted heat from interfering with the sensitive electronics and degrading the quality of the images. These sensors have their own dedicated cooling system, which will only be activated once the electronic cooling system is stable. Once these critical steps are completed, the teams will power on the CCDs and test the control and data acquisition systems to ensure the camera communicates properly with the computers. The camera will then be fully operational.

“Building the camera was never routine and we still have new challenges and problems to solve,” explains Marshall. “But now, as we’re getting ready for the first images, we are transferring the knowledge to the observing specialists and commissioning scientists who shadow our work and often drive the start-up, with supervision. It’s really exciting!”

A few meters away, on the scaffold next to the camera, Yijung Kang, observing specialist and postdoctoral researcher at SLAC, is ready to operate the vacuum system. “All the observing team is really excited to prepare for operations! We are now working closely with the other teams, preparing tests and procedures to ensure the successful launch of our decade-long science mission.”

The work is methodical and demanding, and involves interconnected systems that require a comprehensive understanding of the entire camera. Experts in vacuum systems, cooling, and electronics play a critical role in the process. It is not enough to be an expert in one specific area — one must have a deep, holistic knowledge of the camera. Every system, every component, every adjustment must be carefully anticipated to ensure perfect operation.

Yousuke Utsumi, camera operations scientist and associate professor at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, knows the team is up to the challenge. “The work on the camera is progressing well, and we are confident that any issues that come up, even the most unexpected ones, will be resolved.”

In just a few weeks, once these critical steps are completed and the CCDs are activated, another breathtaking moment will come: The camera’s lens cap will be removed. “It is just like any standard camera lens cap, but this one is five and a half feet wide, and we will use a crane to lift it!” says Utsumi. Then starlight will pour into the LSST Camera for the very first time. At this point, the observing specialists will take control. They will select the portion of the sky to observe, point the telescope, and run the computer program that will capture the first photons. Shortly after, the first images of the sky will be displayed on three giant screens in the control room, marking the beginning of an extraordinary cinematic adventure.

Just like a director meticulously fine-tuning the first shots of a film, the teams will spend a few more weeks refining the telescope and the camera, perfecting focus and optical alignment, capturing calibration images, ensuring smooth and stable operation, and preparing for any potential technical issues. Only then will the greatest astronomical film ever made officially begin.

March 12, 2025

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory installs LSST Camera on telescope

Using the largest digital camera in the world, Rubin Observatory will soon be ready to capture more data than any other observatory in history.

More information

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, is a groundbreaking new astronomy and astrophysics observatory under construction on Cerro Pachón in Chile, with first light expected in 2025. It is named after astronomer Vera Rubin, who provided the first convincing evidence for the existence of dark matter. Using the largest camera ever built, Rubin will repeatedly scan the sky for 10 years and create an ultra-wide, ultra-high-definition, time-lapse record of our Universe.

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory is a joint initiative of the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science (DOE/SC). Its primary mission is to carry out the Legacy Survey of Space and Time, providing an unprecedented data set for scientific research supported by both agencies. Rubin is operated jointly by NSF NOIRLab and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. NSF NOIRLab is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) and SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the DOE. France provides key support to the construction and operations of Rubin Observatory through contributions from CNRS/IN2P3. Rubin Observatory is privileged to conduct research in Chile and gratefully acknowledges additional contributions from more than 40 international organizations and teams.

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency created by Congress in 1950 to promote the progress of science. NSF supports basic research and people to create knowledge that transforms the future.

The DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.

NSF NOIRLab, the U.S. National Science Foundation center for ground-based optical-infrared astronomy, operates the International Gemini Observatory (a facility of NSF, NRC–Canada, ANID–Chile, MCTIC–Brazil, MINCyT–Argentina, and KASI–Republic of Korea), NSF Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO), NSF Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), the Community Science and Data Center (CSDC), and NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory (in cooperation with DOE’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory). It is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with NSF and is headquartered in Tucson, Arizona.

The scientific community is honored to have the opportunity to conduct astronomical research on I’oligam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) in Arizona, on Maunakea in Hawai‘i, and on Cerro Tololo and Cerro Pachón in Chile. We recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence of I’oligam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) to the Tohono O’odham Nation, and Maunakea to the Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) community.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators. SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.