Sharpening our cosmic focus

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory is gearing up to illuminate the universe’s darkest secrets with groundbreaking new technology.

Preparing for the greatest cosmic movie ever made

Now that NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s LSST Camera has been installed, what’s next?

Three decades ago, physicist Tony Tyson sat in the control room of the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope, located on a mountaintop in Chile. At the time, the Blanco telescope – part of Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, a Program of NSF NOIRLab – was one of the largest and most advanced telescopes in the world.

Tyson and his team were supporting astronomers studying galaxies and hunting for distant supernovae with a camera Tyson had helped build. What the supernova team found was unexpected: The universe appeared to be expanding faster than any model predicted. At first, they couldn’t believe it. But as more data came in, it became undeniable.

This observation was one of the first hints that something was deeply hidden from our understanding of the universe – a clue that would later lead to the discovery of what we call dark energy, the force behind the accelerating expansion of the universe.

Rubin’s chief scientist and professor at UC DavisIt means that there’s new physics around the corner."

Tyson points out that “95% of the universe is made of something we don’t understand. We have no idea what dark matter and dark energy are, which I think is really fun,” he says. “It means that there’s new physics around the corner.”

Tyson and his collaborators, who planned to use the telescope to map dark matter, were already thinking about what might come next.

“We asked ourselves: Could we build a bigger telescope to collect more light and a camera with more pixels to map the universe?” Tyson says. “With computing power advancing rapidly to handle the enormous data such a facility would generate, it all felt possible.”

These questions inspired the effort to build the new observatory, initially called the Dark Matter Telescope project. The idea was ambitious: Build a much larger telescope with a giant camera capable of scanning the entire visible sky, discovering billions of galaxies instead of just thousands. Tyson submitted an 11th-hour proposal to the 2000 National Academy of Science's Decadal Survey of Astronomy & Astrophysics, a once-in-a-decade prioritization of the field’s grandest ambitions.

Rubin’s chief scientist and professor at UC DavisThey loved that because this new telescope would do much more than just map dark matter."

“The proposal talked mostly about gravitational lensing and mirages and mapping dark matter,” he says. “But on the last page, I had a picture of an Earth-threatening asteroid. They loved that because this new telescope would do much more than just map dark matter.”

The community embraced it, renaming it first the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST). In 2019, the U.S. Congress officially renamed the observatory to honor Vera C. Rubin, a pioneer in dark matter research. The LSST acronym was preserved and applied to the survey name, which now stands for the Legacy Survey of Space and Time.

Returning to the scene of the dream

Tyson, now Rubin’s chief scientist and a professor at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis), has been the project’s driving force. As founding director for over a decade, he spearheaded efforts to secure private and federal funding, working with tech industry allies and academic partners, and a growing team of scientists, engineers and technicians to turn the vision into reality.

Rubin Observatory’s defining feature is its ability to rapidly scan the entire visible southern sky with unprecedented depth and speed. Unlike traditional observatories, which focus on narrow areas, Rubin’s 8.4-meter telescope and its 3,200-megapixel camera will capture 10-square-degree images – an area of sky equivalent to about 45 full moons – roughly every 40 seconds.

“We’ll cover the sky repeatedly over 10 years,” Tyson says, “sending alerts within two minutes for anything that moves or explodes.”

This unmatched speed enables real-time detection of transient events like supernovae, asteroids and other cosmic phenomena.

The Rubin group chose to build the observatory on Cerro Pachón, just a few kilometers from where Tyson first dreamed up the project, to benefit from the minimal cloud cover, low light pollution and stable atmospheric conditions. The unique design of the telescope allows for extremely rapid repointing that is crucial for Rubin, as it allows the telescope to efficiently scan large portions of the sky, capture transient events and gather data in real time.

Time to focus

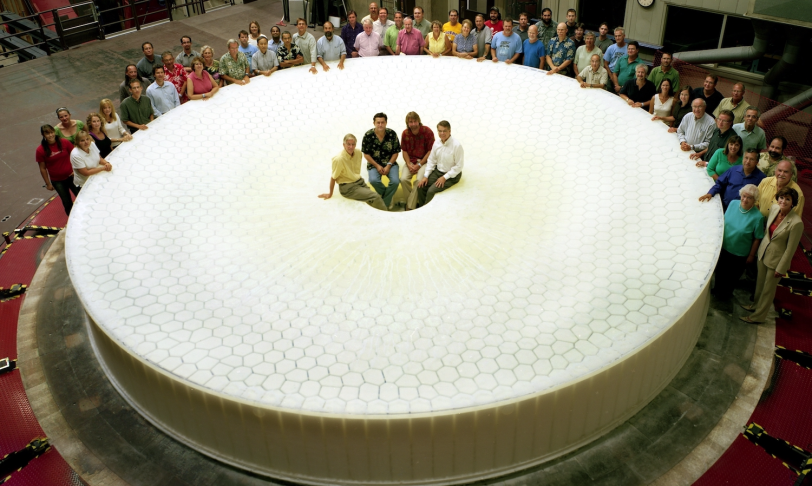

At the heart of Rubin’s groundbreaking observations is the largest digital camera ever built, constructed at the Department of Energy’s (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Tyson said the group chose SLAC in part for its state-of-the-art facilities, skilled engineers and proven track record, but the deciding factor was the team. With experienced leaders like Steve Kahn, who served as director of the LSST Camera project (and later as Rubin Observatory director) and led the initial camera work, along with the involvement of skilled engineers and talented students, the team’s expertise and commitment were crucial to the success of the LSST Camera's construction.

Rubin’s chief scientist and professor at UC DavisYou need all those things – facilities, scientists, engineers and experience – but most importantly, you need people who are committed to taking ownership of the camera."

“You need all those things – facilities, scientists, engineers and experience – but most importantly, you need people who are committed to taking ownership of the camera,” Tyson says. “In the end, it was obvious that SLAC was the right place to do it.”

New physics around the corner

The observatory will tackle some of the universe’s greatest mysteries, including dark matter and dark energy.

Tyson sees these unknowns as opportunities for Rubin to uncover clues that could rewrite our understanding of physics. Using weak gravitational lensing, Rubin will map dark matter with unparalleled precision. This technique measures how massive foreground galaxies bend light from distant background galaxies, creating a "cosmic mirage" that distorts their shapes – a distortion scientists will use to "weigh" the unseen dark matter holding galaxies together. They will also track how fast the universe is expanding, testing whether that speed varies over time.

Over the next decade, Rubin will catalog an estimated 17 billion stars, 20 billion galaxies and millions of astronomical phenomena, generating 60 petabytes of raw data. Hundreds of petabytes of data will be processed in total, including simulations to test models of the universe, all made possible by advancements in computing power. After its 10-year survey, Rubin’s flexible design could accommodate new instruments, extending its scientific lifespan.

Rubin’s data will complement other observatories like the Euclid Space Telescope and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, enhancing measurements with additional tools to probe the universe’s expansion history with greater precision. Beyond cosmology, its rapid scans will catalog millions of supernovae, asteroids and other transient objects, providing a dynamic, real-time census of the sky.

Rubin’s data policy ensures that a significant portion of the data it generates will eventually be accessible to anyone, not just professional astronomers and physicists, allowing the public to explore the cosmos in unprecedented detail.

For Tyson, now that construction is almost complete, the excitement lies in the unknown. More powerful technology and cutting-edge equipment increase the chances of discovering something new and unexpected.

Rubin’s chief scientist and professor at UC DavisI’m eager to see what others might uncover by examining the data with fresh eyes."

“I’m eager to see what others might uncover by examining the data with fresh eyes,” he says. “Someone, maybe a citizen scientist, will look at the data and see something that doesn’t fit any known category – like a new kind of cosmic object – and that could lead to a breakthrough that changes our understanding of the universe.”

More information

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, is a groundbreaking new astronomy and astrophysics observatory under construction on Cerro Pachón in Chile, with first light expected in 2025. It is named after astronomer Vera Rubin, who provided the first convincing evidence for the existence of dark matter. Using the largest camera ever built, Rubin will repeatedly scan the sky for 10 years and create an ultra-wide, ultra-high-definition, time-lapse record of our Universe.

NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory is a joint initiative of the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science (DOE/SC). Its primary mission is to carry out the Legacy Survey of Space and Time, providing an unprecedented data set for scientific research supported by both agencies. Rubin is operated jointly by NSF NOIRLab and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. NSF NOIRLab is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) and SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the DOE. France provides key support to the construction and operations of Rubin Observatory through contributions from CNRS/IN2P3. Rubin Observatory is privileged to conduct research in Chile and gratefully acknowledges additional contributions from more than 40 international organizations and teams.

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent federal agency created by Congress in 1950 to promote the progress of science. NSF supports basic research and people to create knowledge that transforms the future.

The DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.

NSF NOIRLab, the U.S. National Science Foundation center for ground-based optical-infrared astronomy, operates the International Gemini Observatory (a facility of NSF, NRC–Canada, ANID–Chile, MCTIC–Brazil, MINCyT–Argentina, and KASI–Republic of Korea), NSF Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO), NSF Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), the Community Science and Data Center (CSDC), and NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory (in cooperation with DOE’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory). It is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with NSF and is headquartered in Tucson, Arizona.

The scientific community is honored to have the opportunity to conduct astronomical research on I’oligam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) in Arizona, on Maunakea in Hawai‘i, and on Cerro Tololo and Cerro Pachón in Chile. We recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence of I’oligam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) to the Tohono O’odham Nation, and Maunakea to the Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) community.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators. SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.