A day in the life of a mountaintop telescope builder

Margaux Lopez is one of a team of engineers preparing the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile for the arrival of the largest digital camera ever built for astrophysics and cosmology.

By Joe Howlett

When she’s in Chile, Margaux Lopez starts most days nine thousand feet below her place of work. At 6:30 a.m. she boards a bus to begin the steep climb from La Serena, Chile’s second-oldest city, to the top of Cerro Pachón, a mountain in the Chilean Andes.

“It’s an hour of two-lane, paved road, then an hour of windy dirt road. It’s definitely harder to sleep for the second hour,” she says of the journey.

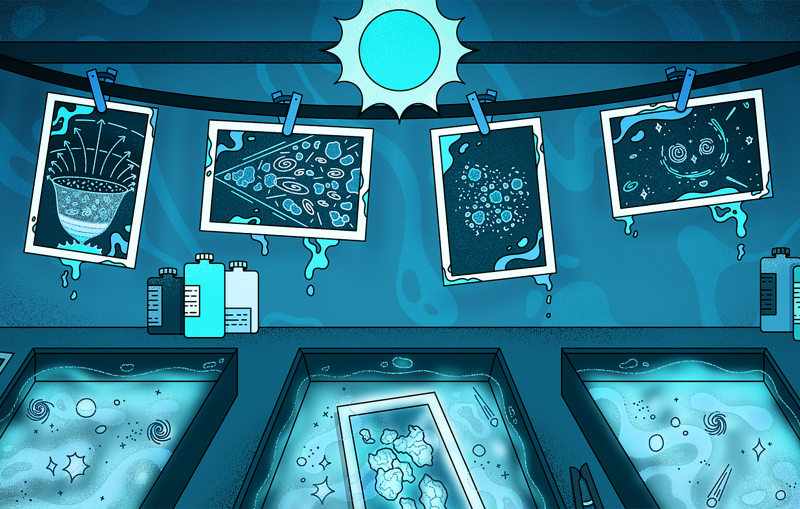

So why does she do this? Lopez is one of a team of engineers hard at work preparing for the arrival of the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) camera, the largest digital camera ever built for astrophysics and part of Vera C. Rubin Observatory. When the camera is shipped to Chile and installed onto the 8.4 meter Simonyi Survey Telescope, Lopez and her team’s hard work will result in the most detailed and far-reaching images of the night sky ever taken.

Once it starts recording data, the observatory will let astronomers measure the faint glow of stars lost in the vast space between galaxies. Researchers expect that what they learn from that light will teach us about the evolutionary history of the universe, the nature of dark matter, and more.

Working toward that goal has so far taken many long days of preparation by the team. Each of those days, sleepy scientists, engineers, and technicians step out of the bus at 8:30 a.m. on the hilltop, where breakfast is served to fuel them up for a grueling day of telescope-building.

The workday then begins with a meeting to organize tasks for the day. "Sometimes the telescope team needs the crane, and sometimes the camera team is trying to install hardware, and sometimes the telescope's moving," Lopez said. “Now that so many people are working in the same space, there’s a lot of coordination to be done so we’re not all on top of each other.”

Keeping things cool

Lopez’s current focus on the summit is preparing the refrigeration lines that will keep the camera’s delicate sensors cool once it’s operational. In order for the camera to record the faint light from a faraway galaxy, for example, the scientists need to block out all other light, including the dim glow of a too-warm instrument.

“If there’s external heat, the sensors will see false positives and higher background noise,” said Lopez. But sensors at -100 degrees Celsius can’t be exposed to air, or water vapor in that air will freeze onto the sensitive electronics and damage them. So the entire assembly needs to be placed inside a protective vacuum container.

“Those refrigeration systems have been one of the biggest ongoing challenges on the project,” said Lopez. Since the refrigerators that send coolant through the system are mounted underneath the floor of the telescope, the team had to construct long coolant lines that run up the entire 3-story telescope to where the camera is mounted.

The process was tedious and slower than hoped for, but Lopez never lost sight of its importance. “We need to make the best instrument we can that works as reliably as possible, so that we can actually do the science we're hoping to do. We can’t cut corners.” Lopez also has somewhat more mundane things to do when she travels to Chile, but it’s no less important to keep the broader goal in sight. “This past trip, we were cleaning and organizing the clean room at the summit, which is kind of boring but very necessary before bringing in this giant camera,” said Lopez.

As the only fully bilingual camera engineer, she often doubles as translator between her team and their Chilean coworkers, or even between other groups on site. “It definitely means that I get involved in a lot of things that I perhaps wouldn't otherwise,” she said, “But it makes the environment much better if you can be friendlier with everyone than just an ‘hola’.”

Life down the mountain

By 4:30 p.m., it’s time to board the two-hour bus back to La Serena.

Once a week, Lopez stays at a hotel on the hilltop instead of going down. “It's much nicer to spend the night. You get a bunch of extra hours of work in, and you don't have to spend those four hours on a bus going down and back up.”

Still, Lopez is happy to come down the hill, especially now that she spends most of her time stateside. “I lived fulltime in Chile for 3 years, and I have some very close friends that I’m really glad to catch up with when I’m there.”

Many of these friends come from her stint playing semi-professional soccer in La Serena. “I still occasionally play pickup with my friends in the evenings.” When she’s not kicking the ball around with her former teammates, Lopez is hitting the dance floor or scaling Chile’s gorgeous cliffsides. “I dance salsa and bachata, and do a lot of climbing at local crags on the weekends.”

When she’s back in California, Lopez is mostly making plans for the critical moment when the camera is ready to ship. “I'm not working on making the camera function. I'm asking ‘How do we carefully pack up all of this stuff in a logical way, and get it to Chile safely?’”

The shipment isn’t easy to coordinate, since the camera and all the other components that help make it work need to be packaged without any delays. The large, awkwardly-shaped mechanical device that controls the camera’s shutter posed a particular challenge, for instance.

“I had to design a sort of cradle to hold it, and then we built a crate to ship it in a specific orientation,” she said.

Since much of the camera support hardware will be in use until the very last minute, the several dozen crates and packing lists need to be made long before anything can actually be packed. “I’m sure there’s going to be something I missed, but I’m doing my best to make sure everything is planned for.”

For Lopez, the years of contingency planning and bumpy bus rides will all be worth it when the LSST camera sees first light – the next step in a timeless human journey. “We've always gone to the tops of mountains that no one's been to,” she said. “There's this kind of human need for knowledge and understanding and discovery. And I think this is the modern reflection of that.”

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.