Researchers aim to make cheaper fuel cells a reality

The team reduced the amount of expensive platinum group metals needed to make an effective cell and found a new way to test future fuel cell innovations.

By Joe Howlett

As the world turns to greener power sources, it also needs to figure out how to store energy for times when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow.

One leading contender, the hydrogen fuel cell, just got a big boost, thanks to fundamental research stemming from the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University, and the Toyota Research Institute (TRI), that was recently translated to practice in a fuel cell device via a collaboration between Stanford and Technion Israel Institute of Technology.

“Hydrogen fuel cells have really great potential for energy storage and conversion, using hydrogen as an alternative fuel to, say, gasoline,” said Michaela Burke Stevens, an associate scientist with SLAC and Stanford University's joint SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis and one of the senior authors on the study. “But it's still fairly expensive to run a fuel cell.”

The problem, Burke Stevens said, is that fuel cells typically rely on a catalyst – packed with expensive platinum group metals (PGM) – that boosts the chemical reaction that makes the system work. That led Burke Stevens and her colleagues to search for ways to make the catalyst cheaper, but making such a fundamental change to a fuel cell’s chemistry is a daunting challenge: Scientists often find a catalyst that works in their small lab setup doesn't work out so well when a company tries it in a real-world fuel cell.

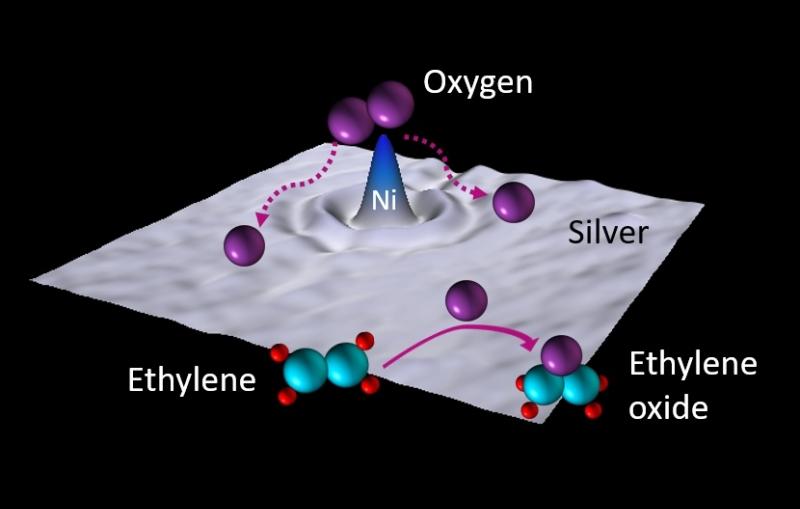

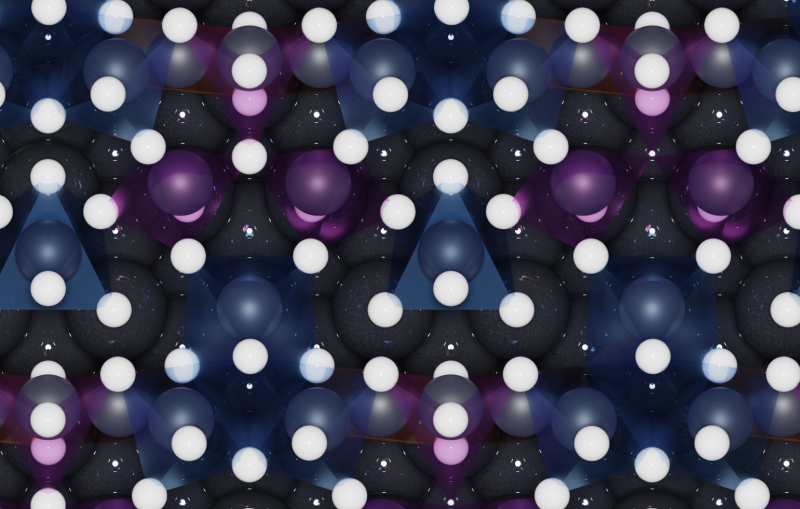

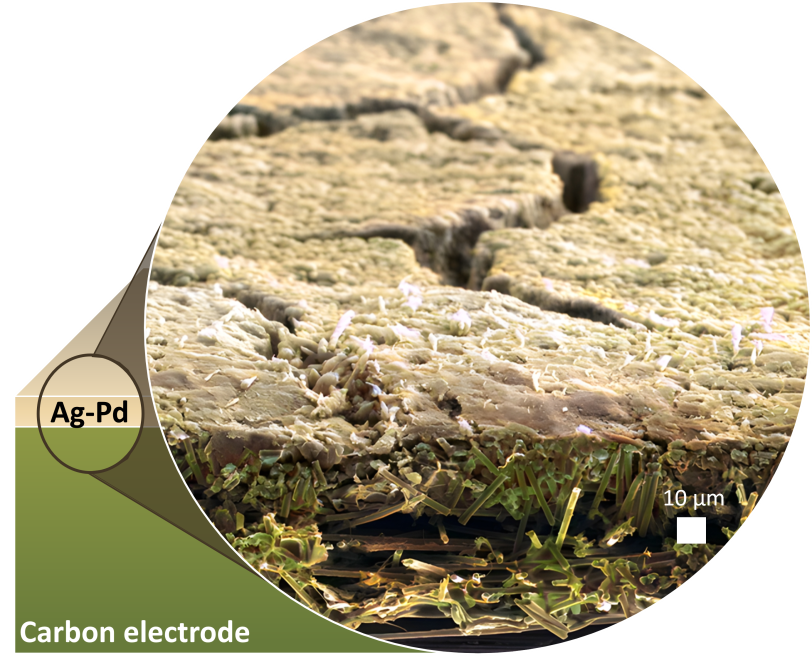

This time, the researchers balanced costs, by partially replacing PGMs with a cheaper alternative, silver; but the real key was to simplify the chemical recipe for getting the catalyst onto the cell’s electrodes. Scientists typically mix the catalyst into a liquid and then spread it onto the mesh electrode, but these catalyst recipes don’t always play out the same way in different lab environments with different tools – making it difficult to translate the work into real-world applications. “Wet chemical processes are not particularly resilient with respect to laboratory conditions,” said Tom Jaramillo, director of SUNCAT, which made the collaboration possible.

To get around that issue, the SLAC team instead used a vacuum chamber for more controlled depositions of their new catalyst onto electrodes. “This high-vacuum tool is a very ‘what you see is what you get’ type of method,” said Jaramillo. “As long as your system is calibrated well, in principle, people can reproduce it readily.”

To ensure that others could reproduce their approach and apply it directly to full-scale fuel cells, the team worked with experts at Technion, who showed that the method worked in a practical fuel cell.

“This project was not set up to do the fuel cell testing here, so we were really fortunate that the lead Stanford graduate student on the project, José Zamora Zeledόn, formed a connection with Dario Dekel and his PhD student John Douglin at Technion. They were set up to test the actual fuel cells, so it was a really nice combination of resources to put together,” said Burke Stevens.

Together, the two teams found that by substituting cheaper silver for some of the PGMs used in previous catalysts, they could achieve an equally effective fuel cell with a much lower price tag –and now that they have a proven method of developing catalysts, they can start testing more ambitious ideas. “We could try going entirely PGM-free,” said Jaramillo. Dekel, a chemical engineering professor and director of the Grand Technion Energy Program at Technion, was equally excited by the partnership’s potential. “This has great benefits for the research of fuel cells in the academy as well as for practical catalyst development in the fuel cell industry,” he said.

Looking forward, Jaramillo said, research like this will decide whether fuel cells can fulfill their potential. “Fuel cells are really looking exciting and interesting for heavy-duty transportation and clean energy storage,” said Jaramillo, “but it’s ultimately going to come down to lowering cost, which is what this collaborative work is all about.”

This research was funded in part by the DOE's Office of Science through the SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis, a SLAC-Stanford joint institute, and the Toyota Research Institute.

Citation: J. C. Douglin, et al., Nature Energy, November 9, 2023 (DOI: 10.1038/s41560-023-01385-7)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.