New catalyst could dramatically cut methane pollution from millions of engines

Researchers demonstrate a way to remove the potent greenhouse gas from the exhaust of engines that burn natural gas.

Individual palladium atoms attached to the surface of a catalyst can remove 90% of unburned methane from natural-gas engine exhaust at low temperatures, scientists reported today in the journal Nature Catalysis.

While more research needs to be done, they said, the advance in single atom catalysis has the potential to lower exhaust emissions of methane, one of the worst greenhouse gases, which traps heat at about 25 times the rate of carbon dioxide.

Researchers from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Washington State University showed that the catalyst removed methane from engine exhaust at both the lower temperatures where engines start up and the higher temperatures where they operate most efficiently, but where catalysts often break down.

“It’s almost a self-modulating process which miraculously overcomes the challenges that people have been fighting – low temperature inactivity and high temperature instability,” said Yong Wang, Regents Professor in WSU’s Gene and Linda Voiland School of Chemical Engineering and Bioengineering and one of four lead authors on the paper.

A growing source of methane pollution

Engines that run on natural gas power 30 million to 40 million vehicles worldwide and are popular in Europe and Asia. The natural gas industry also uses them to run compressors that pump gas to people’s homes. They are generally considered cleaner than gasoline or diesel engines, creating less carbon and particulate pollution.

However, when natural-gas engines start up, they emit unburnt, heat-trapping methane because their catalytic converters don’t work well at low temperatures. Today's catalysts for methane removal are either inefficient at lower exhaust temperatures or they severely degrade at higher temperatures.

“There’s a big drive towards using natural gas, but when you use it for combustion engines, there will always be unburnt natural gas from the exhaust, and you have to find a way to remove that. If not, you cause more severe global warming,” said co-author Frank Abild-Pedersen, a SLAC staff scientist and co-director of the lab’s SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis, which is run jointly with Stanford University. “If you can remove 90% of the methane from the exhaust and keep the reaction stable, that’s tremendous.”

A catalyst with single atoms of the chemically active metal dispersed on a support also uses every atom of the expensive and precious metal, Wang added.

“If you can make them more reactive,” he said, “that’s the icing on the cake.”

Unexpected help from a fellow pollutant

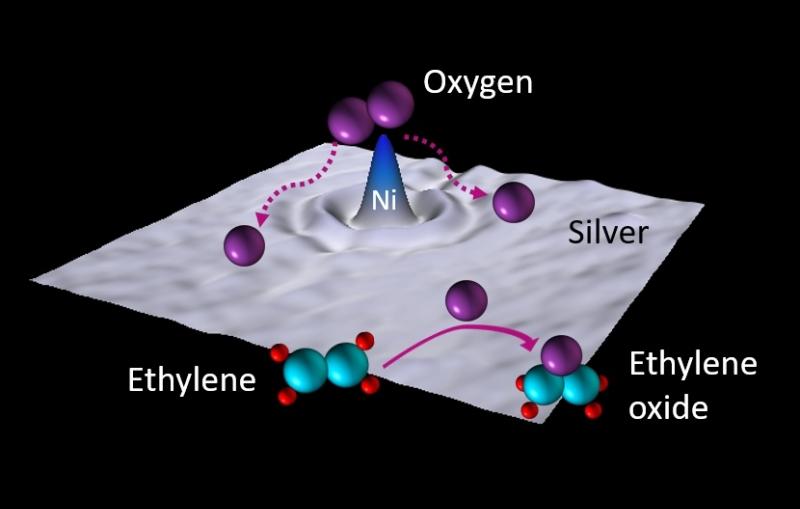

In their work, the researchers showed that their catalyst made from single palladium atoms on a cerium oxide support efficiently removed methane from engine exhaust, even when the engine was just starting.

They also found that trace amounts of carbon monoxide that are always present in engine exhaust played a key role in dynamically forming active sites for the reaction at room temperature. The carbon monoxide helped the single atoms of palladium migrate to form two- or three-atom clusters that efficiently break apart the methane molecules at low temperatures.

Then, as the exhaust temperatures rose, the clusters broke up into single atoms and redispersed, so that the catalyst was thermally stable. This reversible process enabled the catalyst to work effectively and used every palladium atom the entire time the engine was running – including when it started cold.

“We were really able to find a way to keep the supported palladium catalyst stable and highly active and, because of the diverse expertise across the team, to understand why this was occurring,” said SLAC staff scientist Christopher Tassone.

The researchers are working to further advance the catalyst technology. They would like to better understand why palladium behaves in one way while other precious metals such as platinum act differently.

The research has a way to go before it will be put inside a car, but the researchers are collaborating with industry partners as well as with DOE’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory to move the work closer to commercialization.

Along with Wang, Abild-Pedersen, and Tassone, Dong Jiang, senior research associate in WSU’s Voiland School, also led the work. The work was funded by the DOE Office of Science, and included research carried out at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), Argonne National Laboratory’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), which are all DOE Office of Science user facilities.

This article has been adapted from a press release written by Washington State University.

Citation: Dong Jiang et al., Nature Catalysis, 20 July 2023 (10.1038/s41929-023-00983-8)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.