First Nanoscale Look at How Lithium Ions Navigate a Molecular Maze to Reach Battery Electrode

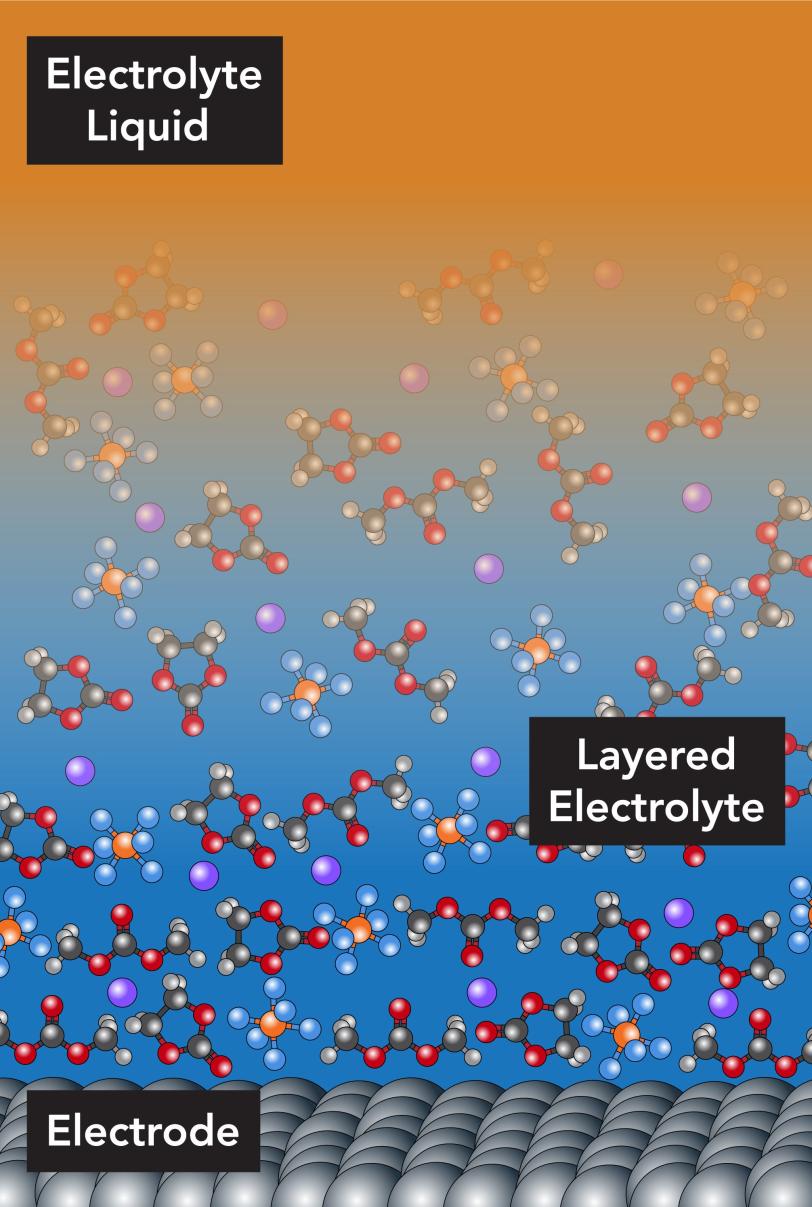

Lithium ions have to travel through layers of molecules in the electrolyte liquid before they can enter or leave a lithium-ion battery electrode. Tweaking this process could help batteries charge faster.

By Glennda Chui

The lithium-ion batteries that power laptops, electric cars and so many other modern gadgets operate on a simple plan: Lithium ions shuttle back and forth between two electrodes, inserting themselves into one of the electrodes as the battery charges and moving across to the other as the battery drains. The speed and ease of their travel through the battery’s liquid electrolyte help determine how fast the battery can charge.

Now scientists have taken the first close look at what happens within a few nanometers of the electrode, where the normally freely moving electrolyte molecules organize themselves into layers that stand directly in the lithium ions’ paths.

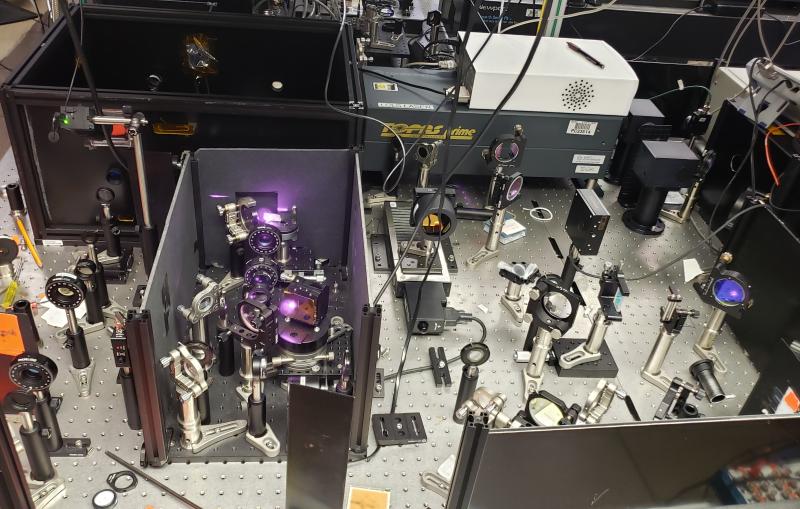

They directly observed this layering for the first time in X-ray experiments at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. The results suggest that changing the concentration of lithium ions in the electrolyte might change the arrangement of the molecular layers and make it easier for the ions to get in and out of the electrode.

“That process of the ions finding their way into the electrode is very important in terms of how fast you can charge the battery and how long the battery lasts,” said Michael Toney, a distinguished staff scientist at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) and co-leader of the study. “Understanding the nanoscale details of how this works could suggest ways to increase charging speed and efficiency.”

The report has been accepted for publication in Energy & Environmental Science, and an advance copy is posted on the journal’s website.

Probing a Commercial Electrolyte

In lithium-ion batteries, the electrolyte consists of lithium and other ions in a solvent, with the solvent molecules moving around as they would in any other liquid. But based on theory and previous computer simulations, scientists had a strong suspicion that something different happened in the tiny volume of the electrolyte that’s right up next to the electrode. Here, they thought, the presence of the electrode’s hard surface would induce the solvent molecules to line up and form orderly layers. However, confirming this through experiments proved difficult.

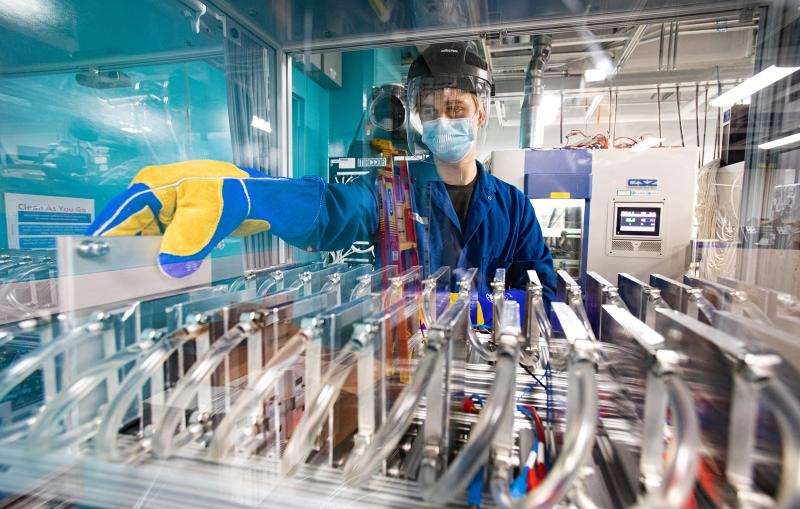

For these latest experiments, Toney’s team used a metal oxide material to represent the electrode, bathed in an electrolyte typically found in commercial lithium-ion batteries.

By focusing a high-brilliance X-ray beam from SSRL on the surface of the electrode and analyzing the X-rays that bounced back through the electrolyte, like light reflecting from a mirror, the researchers were able to determine the structures and positions of individual solvent molecules and lithium ions that were within a few billionths of a meter of the electrode surface, said Hans-Georg Steinrück, a postdoctoral researcher in Toney’s group and co-leader of the experiments. Molecular dynamics simulations complemented and agreed with the experimental results.

“We can see the positions of ions and solvent molecules near the electrode with angstrom resolution, and also see how they are oriented at the surface of the electrode,” Steinrück said. “They’re arranged in well-defined layers at the boundary, and the first layer lies flat, parallel to the surface of the electrode; then they become more disordered, more typical of a liquid, as you move out from the surface.” These ordered layers make it more difficult for the lithium ions to move quickly through the layers and into the electrode.

Shifting Ranks of Molecules

However, as the concentration of lithium ions in the electrolyte increased, the arrangement of the layers changed; it became a bit more orderly, and the layers were farther apart, Steinrück said. This led the researchers to a conclusion that seems almost the opposite of what you’d expect.

“Our hypothesis is that if you want to improve lithium ion transport, you want to decrease the amount of order in the layers, and that means decreasing the lithium ion concentration rather than increasing it,” he said.

Steinrück said the team will be exploring this avenue of research further, adding that the foundational knowledge obtained with this technique can also be applied to studies of other types of next-generation batteries and energy storage systems.

In addition to scientists from the SSRL Materials Science Division, researchers from Stanford University, the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France and the U.S. Army Research Laboratory in Maryland contributed to this study. Funding for the project was provided by the Joint Center for Energy Storage Research, a Department of Energy Innovation Hub; the DOE Office of Science; and the DOE Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program. SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Citation: H.-G. Steinrück et al., Energy & Environmental Science, 24 January 2018 (10.1039/C7EE02724A)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The Joint Center for Energy Storage Research (JCESR), a DOE Energy Innovation Hub, is a major partnership that integrates researchers from many disciplines to overcome critical scientific and technical barriers and create new breakthrough energy storage technology. Led by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory, partners include national leaders in science and engineering from academia, the private sector, and national laboratories. Their combined expertise spans the full range of the technology-development pipeline from basic research to prototype development to product engineering to market delivery.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.