A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been

Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is a lot more complicated.

By Glennda Chui

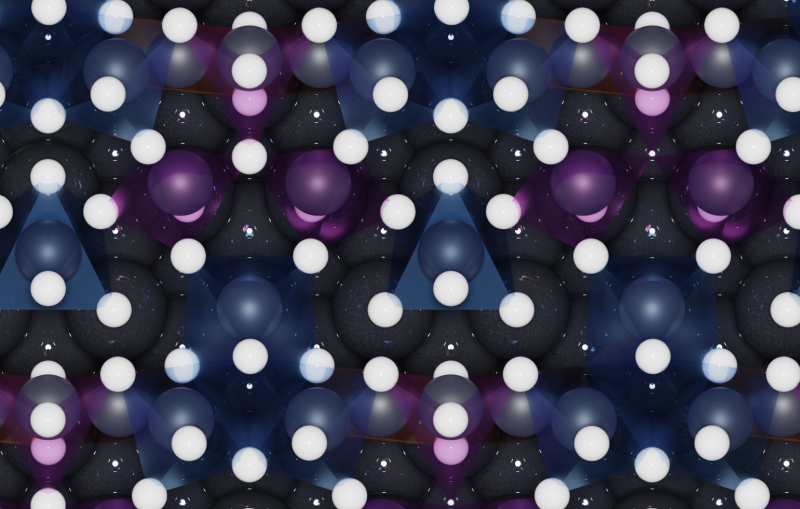

Solid-state batteries store and release charge by nudging ions back and forth between two electrodes. From our usual point of view, the ions flow through the battery’s solid electrolyte like a gentle stream.

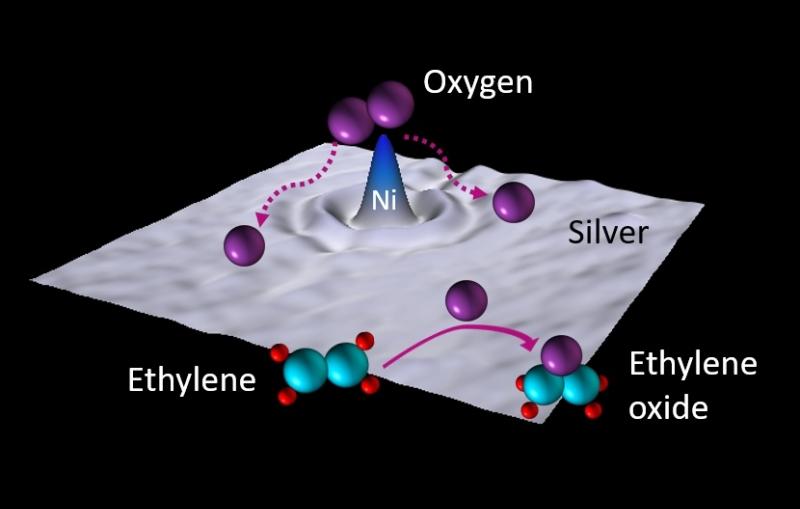

But when seen on an atomic scale, that smooth flow is an illusion: Individual ions hop erratically from one open space to another within the electrolyte’s roomy atomic lattice, nudged in the direction of an electrode by a steady voltage. Those hops are hard to predict and a challenge to trigger and detect.

Now, in the first study of its kind, researchers gave the hopping ions a jolt of voltage by hitting them with a pulse of laser light. To their surprise, most of the ions briefly reversed direction and returned to their previous positions before resuming their usual, more random travels. It was the first indication that the ions remembered, in a sense, where they had just been.

The research team from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University, Oxford University and Newcastle University described what they found in the Jan. 24 issue of Nature.

Electronic cornstarch

“You can think of the ions as behaving like a mixture of cornstarch and water,” said Andrey D. Poletayev, a postdoctoral researcher at Oxford who helped lead the experiment when he was a postdoc at SLAC. “If we gently push this cornstarch mixture, it yields like a liquid; but if we punch it, it turns solid. Ions in a battery are like electronic cornstarch. They resist a hard shake from a jolt of laser light by moving backwards.”

The ions’ “fuzzy memory,” as Poletayev puts it, lasts just a few billionths of a second. But knowing that it exists will help scientists predict, for the first time, what traveling ions will do next – an important consideration for discovering and developing new materials.

An electrolyte designed for speed

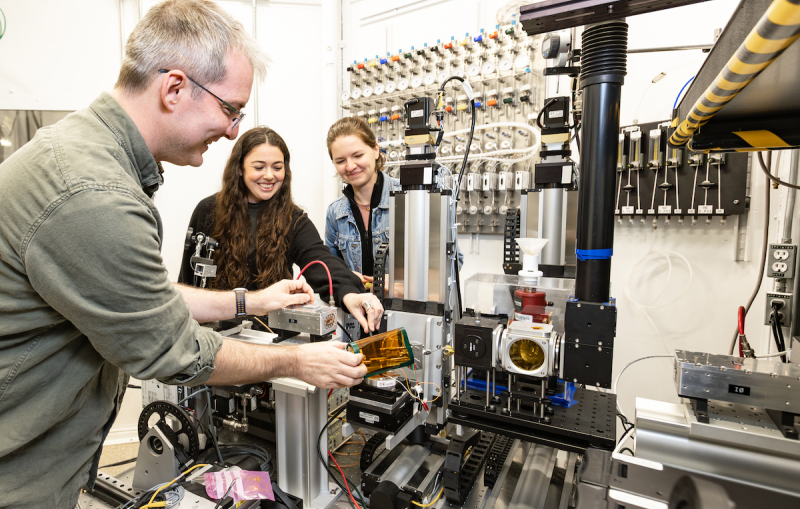

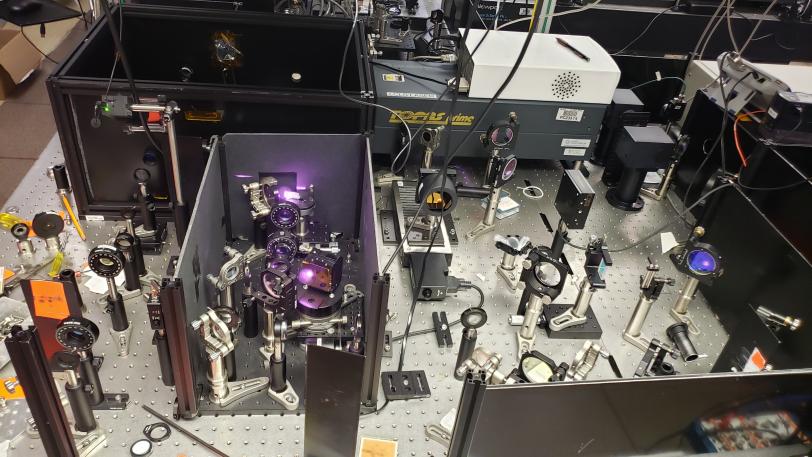

For their experiments in SLAC’s laser lab, the researchers used thin, transparent crystals of a solid electrolyte from a family of materials called beta-aluminas. These materials were the first high-conductivity electrolytes ever discovered. They contain tiny channels where hopping ions can travel fast, and have the advantage of being safer than liquid electrolytes. Beta-aluminas are used in solid state batteries, sodium-sulfur batteries and electrochemical cells.

As ions hopped their way through the beta-alumina’s channels, the researchers hit them with pulses of laser light that were just trillionths of a second long, then measured the light that came back out of the electrolyte.

By varying the time between the laser pulse and the measurement, they were able to precisely determine how the ions’ speed and preferred direction changed in the few trillionths of a second after the jolt from the laser.

Weird and unusual

“There are multiple weird and unusual things going on in the ion hopping process,” said SLAC and Stanford Professor Aaron Lindenberg, an investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) who led the study.

“When we apply a force that shakes the electrolyte, the ion doesn’t immediately respond like in most materials,” he said. “The ion may sit there a while, suddenly jump, then sit there for quite a while again. You might have to wait for some time and then suddenly a giant displacement occurs. So there’s an element of randomness in this process which makes these experiments difficult.”

Until now, the researchers said, the way the ions travel was thought to be a classic “random walk”: They jostle, collide and bumble along, like a drunk person staggering down a sidewalk, but eventually reach some destination in a way that can seem deliberate to an observer. Or think of a skunk releasing stinky spray into a room full of people; the molecules in the spray randomly jostle and collide, but all too quickly reach your nose.

When it comes to the hopping ions, “that picture turns out to be wrong on an atomic scale,” Poletayev said, “but that’s not the fault of the people who came to that conclusion. It’s just that researchers have been investigating ionic transport with macroscopic tools for so long, and they couldn’t observe what we saw in this study.”

The atomic-scale discoveries made here, he said, “will help bridge the gap between the atomic motions that we can model in a computer and a material’s macroscopic performance, which has made our research so complicated.”

Matthias C. Hoffmann, a lead scientist in the Laser Science and Technology Division of SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), built the laser apparatus used in these experiments. Major funding for the study came from the DOE Office of Science.

Citation: Andrey Poletayev et al., Nature, 24 January 2024 (10.1038/s41586-023-06827-6)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.