A day in the life of a machine learning expert

Digital design engineer Abhilasha Dave’s passion for connecting machine learning and hardware is helping SLAC solve its big data challenge through edge machine learning.

By Carol Tseng

One day when she was young, Abhilasha Dave recalls her father replacing their cathode-ray tube TV with an LED (light emitting diode) TV. She was fascinated by how sleek the new TV looked – but she also had lots of questions. “I was so curious as to how this digital thing worked," she said. "How do you go from a big box TV to this LED? How is somebody transporting the video from some place to where I can see it in my home, and everybody else can see it in their homes?”

Her father didn’t have the answers, so instead he encouraged her to try searching in the direction of electronics engineering. Dave immersed herself in the field, earning a bachelor's degree in electronics and communications engineering from Nirma University in India and a master's degree in computer engineering from California State University, Fresno. Along the way, she even took a course on how TVs worked.

But questions still swirled in her head. Dave had studied machine learning and worked with electronic hardware called field programmable gate arrays (FPGAs), which are programmable integrated circuits, and wanted to connect the two. “I wanted to learn more about that connection between hardware and software,” she said.

Dave embarked on stints at academic programs at the University of California, Merced, and University of Stuttgart in search of answers, but then another question loomed. “I got curious about applying machine learning onto FPGAs for scientific applications,” Dave said. “I wanted to take it to the next stage.”

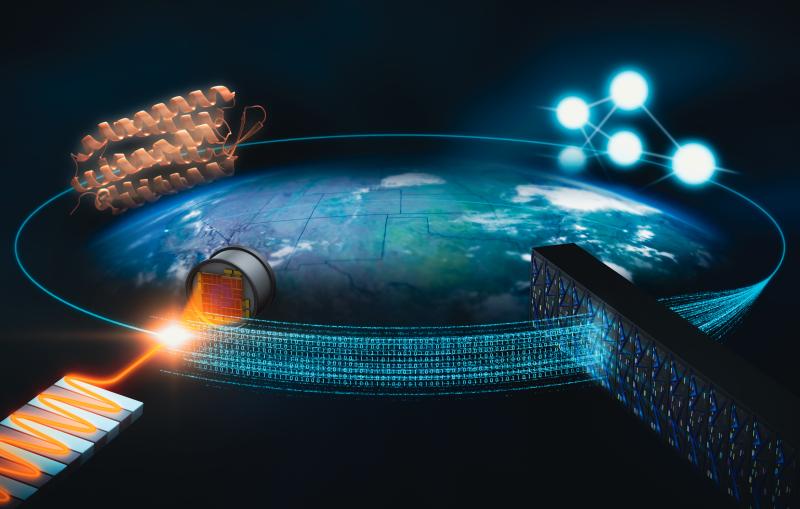

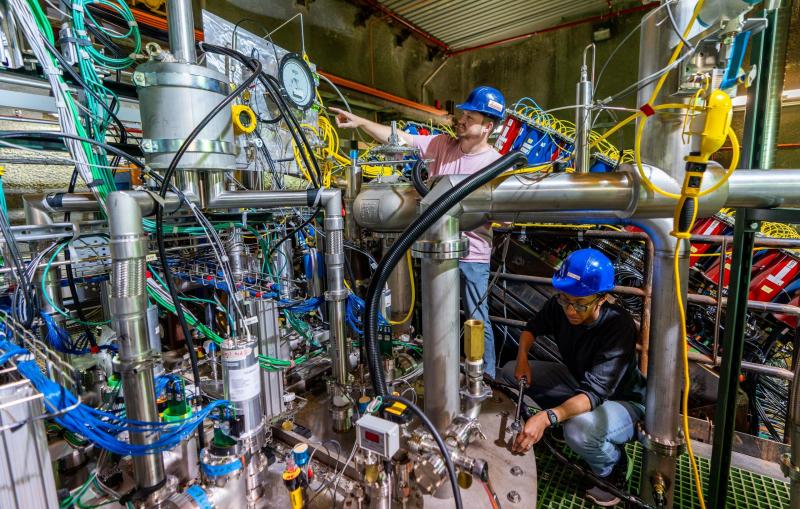

She found her niche at the U.S. Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Today, Dave is a digital design engineer and machine learning expert who is helping the lab solve its big data challenges through developing cutting-edge methods to connect machine learning to hardware. For instance, when SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) facility for X-ray and ultrafast science reaches full capability, which is expected next year, torrents of data will be gushing in at one terabyte per second. Dave compares it to streaming 1,000 full-length movies each second. Conventional methods of storing and processing data on computers or servers are going to be too expensive or simply not possible due to the volume of data and the rate at which it arrives.

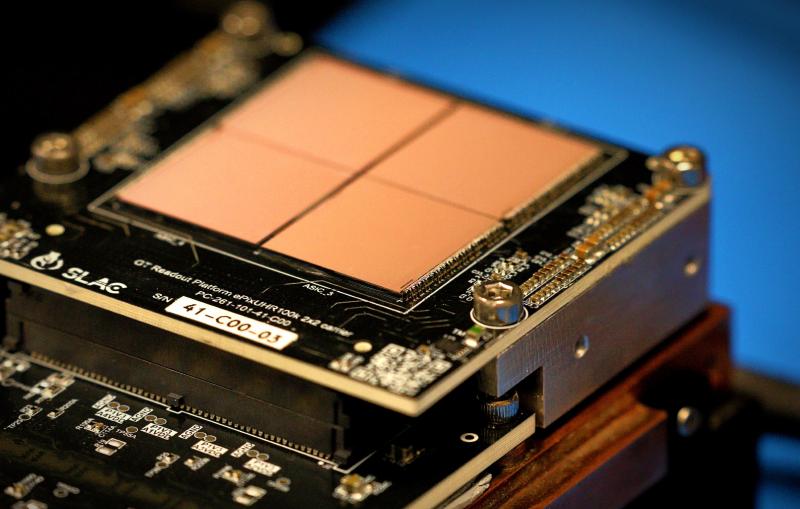

To deal with this influx of data, Dave works with fellow lab experts to develop edge machine learning, or edgeML, techniques. The idea behind edgeML is to process and analyze data as close to a data source – on its edge – as possible. This allows for faster processing and analyzing of data, even decreasing the amount of data that ends up being stored. Examples of edge devices include drones that must process sensor data instantly to navigate safely and self-driving cars, which rely on immediate data processing for split-second decision-making. In LCLS’s case, edgeML models are deployed directly onto FPGAs integrated with the detectors, enabling real-time data processing crucial for high-speed scientific experiments.

The collaborative environment here, where interdisciplinary teams tackle some of the most challenging problems in science, is something I deeply value.

Typical day

Sitting at her desk, Dave faces a familiar challenge. A scientist needs her help to fit a large machine learning model onto an FPGA. The model, which has millions of parameters, classifies X-ray single particle imaging scattering patterns. These types of patterns reveal the three-dimensional structure of single particles, which in this experiment, are nearly 1,000 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair. She considers her options and decides that, for these patterns, they can use fewer parameters and not compromise accuracy. The new, sleeker model, which has the same structure as before, is 98.8% smaller and ready to fit onto the FPGA.

Many times, she points out, the situation is analogous to when an online seller ships a small item wrapped in a lot of paper and placed in a much-too-big box because that is a standard box size they have. Similarly in the machine learning field, she said, “People go with standardized machine learning models or create their own model based on a reference seen in the community.”

Dave can also apply other methods to shrink an oversized machine learning model. One option is to preprocess the raw data, representing it in a much smaller format, so a researcher can use effectively smaller machine learning models. Another method is to replace layers in the original model with more compact and efficient layers.

“I can also compress the model's parameters through quantization, reducing them from 32-bit floating points to 16-bit, 8-bit or even 1-bit binary representations,” she said. "On FPGAs, this process reduces not only the amount of memory required, but also the computation for the neural network.” Computers store information using bits, which is short for binary digits (0 or 1).

Depending on the situation and required accuracy for the neural network, she will elect to use one or a combination of these methods.

Making connections

When not wrangling with machine learning models or compressing data and parameters, she decompresses with long bike rides, video games, and drawing and painting. Her favorite activity is riding her bike by the beach, where she can leave work behind and take in the fresh air and scenic views. She finds video games such as Fortnite and Rocket League fun and engaging. Tapping into her creative side, she is reconnecting with drawing and painting, which she used to do a lot of as a child. “I am restarting with pencil drawing of small scenery and nature and getting into abstract art, like the Dutch pouring technique (a.k.a., Dutch Pour Abstract Art),” said Dave. “I love the freedom to create without limitations.”

But Dave also enjoys connecting machine learning with hardware as well as connecting with fellow lab researchers. The crosscutting nature of her work benefits not only the LCLS community, but also other scientific communities across the lab. “I'm incredibly proud of having the opportunity to push the boundaries of what's possible with technology at SLAC. The collaborative environment here, where interdisciplinary teams tackle some of the most challenging problems in science, is something I deeply value. My work on optimizing and applying machine learning models to handle real-time fast data rates on edge devices, particularly for applications in the superconducting linac at LCLS, high energy physics and fusion energy science, has been especially rewarding,” she said.

For those interested in pursuing a career in machine learning, Dave said to be curious. “Whatever thing you see – electronic device or mechanical tool – find out how it works. The more you think about it, the more you learn about it. Find an application that excites you and try to think how you can apply machine learning to it. That’s where you can connect those dots and make meaningful contributions.”

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

AI and machine learning

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.