Peter Dahlberg and Benjamin Ofori-Okai receive 2021 Panofsky Fellowships at SLAC

Their work helps reveal the inner workings of cells and the behavior of matter under extreme pressures and temperatures.

By Ali Sundermier and Nathan Collins

Peter Dahlberg and Benjamin Ofori-Okai have been named the 2021 Panofsky Fellows at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Dahlberg is developing new methods to study the function and behavior of proteins inside cells, while Ofori-Okai is working to understand matter in extreme conditions, such as those found at the center of the Earth.

The Panofsky Fellowship, named after SLAC's founder and first director Wolfgang K. H. "Pief" Panofsky, recognizes exceptional early-career scientists who would most benefit from the opportunity to do their research at the lab. It provides generous funding for five years of research and an opportunity for continuing appointment at SLAC.

Peter Dahlberg: New probes of biological function

Dahlberg’s journey to SLAC started during his PhD training at the University of Chicago and the DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory, where he used ultrafast spectroscopy to study how the process of photosynthesis unfolds inside cells. It was for him the perfect blend of two interests. “I can get interested in any biological system,” he said, but at the same time “I’m an instrument junkie – I love building new tools and devices.”

That combination led him to a postdoctoral fellowship with Stanford physical chemist W.E. Moerner, who had been working on mapping where different kinds of proteins are located inside cells and how those proteins move around using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. By making specific, individual proteins fluoresce, or light up, this advanced form of microscopy allows researchers to identify their positions and motion. For his part in the development of this microscopy technique, W. E. Moerner shared in the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Still, super-resolution fluorescence microscopy doesn’t give the complete picture. A shortcoming was that the method did not show where proteins were in relation to other parts of the cell, which could be crucial – it matters, for instance, whether a viral protein is gathering near a cell membrane to enter a cell or somewhere else to replicate.

That’s where Dahlberg’s research with Moerner and SLAC and Stanford professor Wah Chiu comes in. He’s been working on ways to combine fluorescence methods with cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), which freezes cells in place in order to take high resolution images of them.

As a Panofsky fellow, Dahlberg will also explore new methods, including one that is slightly lower resolution but can be done much faster and with fewer technical challenges, making it more accessible to SLAC’s large user community.

Dahlberg said he is also looking at developing methods that combine cryo-EM with real-time imaging to freeze individual cells at particular moments of interest, which could yield a more clear sense of cellular dynamics than is currently possible.

And, he said, he is happy to be able to continue working with Moerner and Chiu. “I only applied for one job, really, because this is what I wanted to do next,” he said. “It’s been so fun working with them, and I’d like to continue working with them as I take the next steps in my research.”

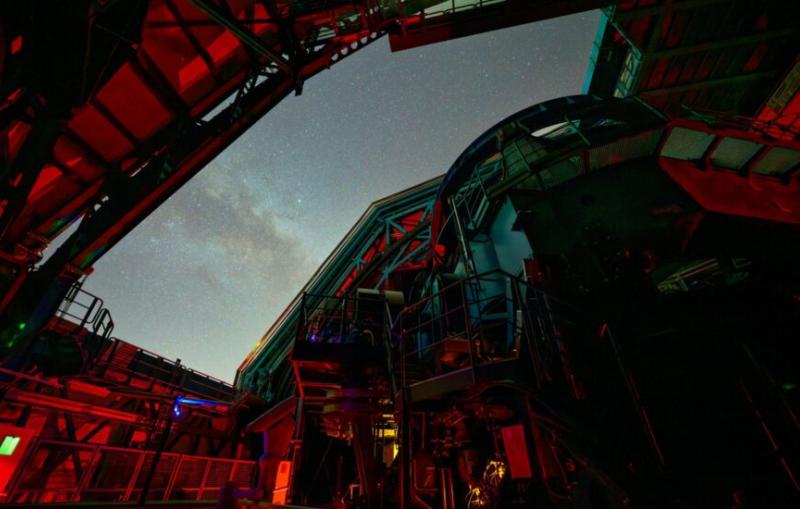

Benjamin Ofori-Okai: The earth’s magnetic dynamo

Ofori-Okai, who is the first Black recipient of the Panofsky fellowship, started his undergraduate career at Yale, moving on to MIT for his PhD. At SLAC, he’s part of the High Energy Density Sciences Division, where he performs experiments at the lab’s Sector-10 laser lab and Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser. He says he spends a lot of time thinking about “how small stuff works, and how that impacts what it does when it’s not so small.”

In particular, he investigates what happens to matter when it’s subjected to the extreme pressures and temperatures one might find in the hearts of planets. By studying how these conditions affect the conductivity of materials in the lab, he hopes to reach a better understanding of how processes in the center of the Earth produce its large magnetic fields.

“You could make the argument that what we’re studying is basic and fundamental,” he says. “But having that understanding is important because it gives you guidance for other problems that need to be solved. Everything is connected to something else, so having that knowledge is a steppingstone to future discoveries and advancements.”

He says he was in the middle of an experiment when he received the email that announced that he would be receiving the fellowship, and he was both honored and excited.

“Having a lot of energy and not really being able to go to sleep was my initial reaction,” he says.

“I see it as an opportunity to tackle things I haven’t done before and push myself in a way that can sometimes be hard to do at the early stages of one’s career.”

In addition to his research on materials in extreme conditions, Ofori-Okai hopes to use the fellowship to explore how to use terahertz radiation, a form of light that is several hundred times less energetic than visible light, to better understand properties of quantum materials that could be harnessed for superconductivity or quantum computing.

He adds that he’s hopeful the fellowship will give him the opportunity to expand his network and connect with scientists in other parts of the lab who are doing related work so that they can team up to push the research even farther.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.