Scientists take first snapshots of ultrafast switching in a quantum electronic device

They discover a short-lived state that could lead to faster and more energy-efficient computing devices.

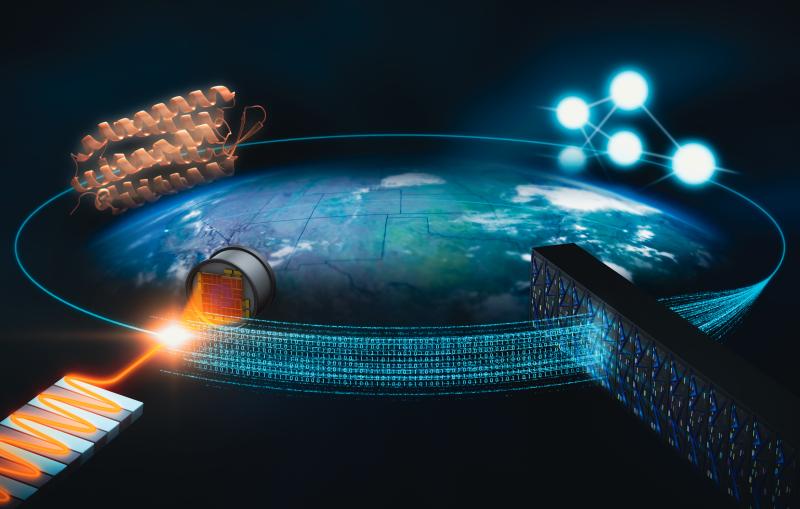

Electronic circuits that compute and store information contain millions of tiny switches that control the flow of electric current. A deeper understanding of how these tiny switches work could help researchers push the frontiers of modern computing.

Now scientists have made the first snapshots of atoms moving inside one of those switches as it turns on and off. Among other things, they discovered a short-lived state within the switch that might someday be exploited for faster and more energy-efficient computing devices.

The research team from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University, Hewlett Packard Labs, Penn State University and Purdue University described their work in a paper published in Science today.

“This research is a breakthrough in ultrafast technology and science,” says SLAC scientist and collaborator Xijie Wang. “It marks the first time that researchers used ultrafast electron diffraction, which can detect tiny atomic movements in a material by scattering a powerful beam of electrons off a sample, to observe an electronic device as it operates.”

Fast voltage pulses trigger a transient metastable phase in vanadium dioxide electrical switches

Capturing the cycle

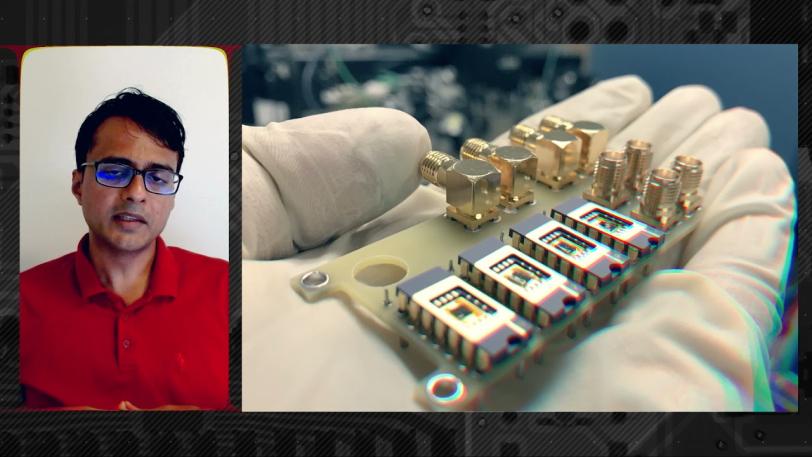

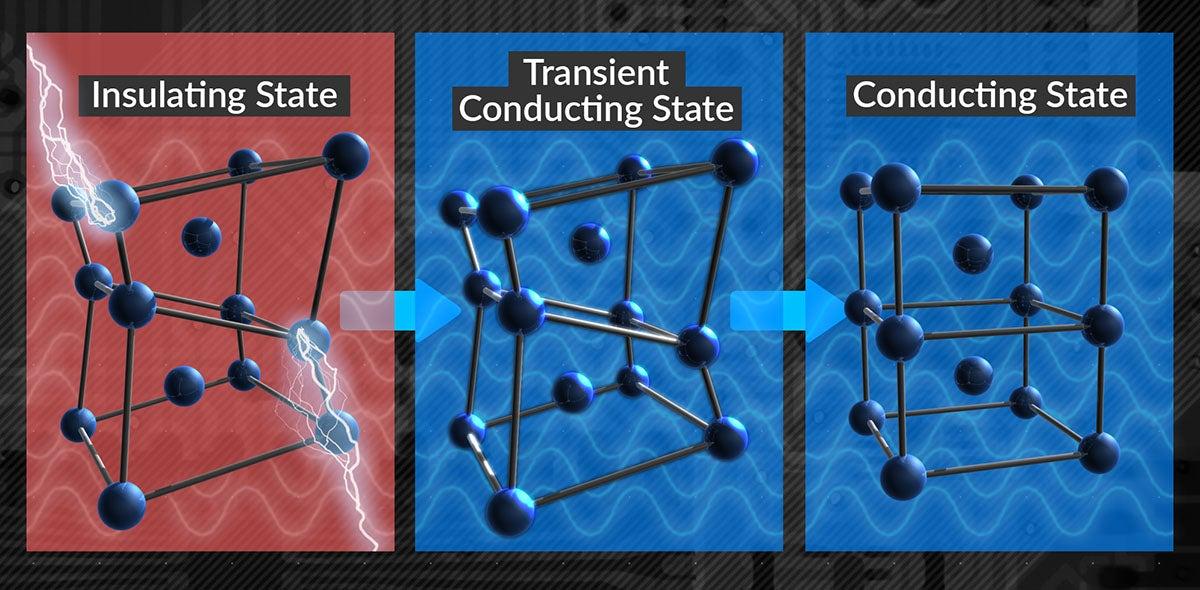

For this experiment, the team custom-designed miniature electronic switches made of vanadium dioxide, a prototypical quantum material whose ability to change back and forth between insulating and electrically conducting states near room temperature could be harnessed as a switch for future computing. The material also has applications in brain-inspired computing because of its ability to create electronic pulses that mimic the neural impulses fired in the human brain.

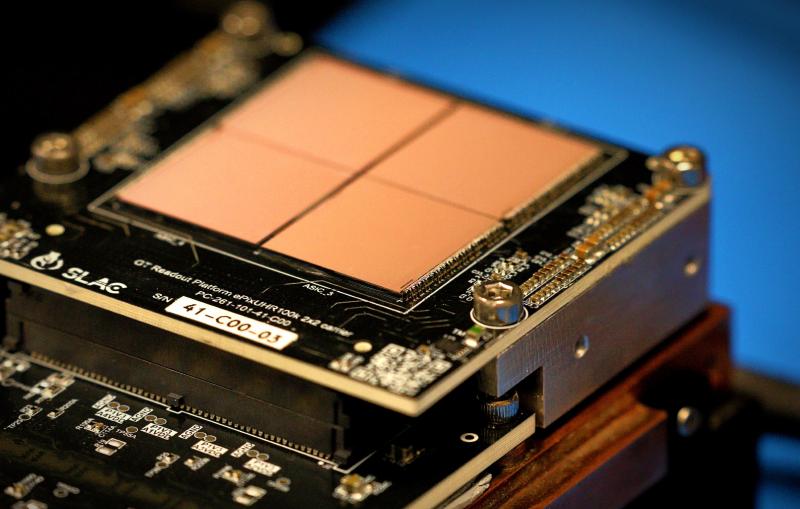

The researchers used electrical pulses to toggle these switches back and forth between the insulating and conducting states while taking snapshots that showed subtle changes in the arrangement of their atoms over billionths of a second. Those snapshots, taken with SLAC’s ultrafast electron diffraction camera, MeV-UED, were strung together to create a molecular movie of the atomic motions.

“This ultrafast camera can actually look inside a material and take snapshots of how its atoms move in response to a sharp pulse of electrical excitation,” said collaborator Aaron Lindenberg, an investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC and a professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Stanford University. “At the same time, it also measures how the electronic properties of that material change over time.”

With this camera, the team discovered a new, intermediate state within the material. It is created when the material responds to an electric pulse by switching from the insulating to the conducting state.

“The insulating and conducting states have slightly different atomic arrangements, and it usually takes energy to go from one to the other,” said SLAC scientist and collaborator Xiaozhe Shen. “But when the transition takes place through this intermediate state, the switch can take place without any changes to the atomic arrangement.”

Opening a window on atomic motion

Although the intermediate state exists for only a few millionths of a second, it is stabilized by defects in the material.

To follow up on this research, the team is investigating how to engineer these defects in materials to make this new state more stable and longer lasting. This will allow them to make devices in which electronic switching can occur without any atomic motion, which would operate faster and require less energy.

“The results demonstrate the robustness of the electrical switching over millions of cycles and identify possible limits to the switching speeds of such devices,” said collaborator Shriram Ramanathan, a professor at Purdue. “The research provides invaluable data on microscopic phenomena that occur during device operations, which is crucial for designing circuit models in the future.”

The research also offers a new way of synthesizing materials that do not exist under natural conditions, allowing scientists to observe them on ultrafast timescales and then potentially tune their properties.

“This method gives us a new way of watching devices as they function, opening a window to look at how the atoms move,” said lead author and SIMES researcher Aditya Sood. “It is exciting to bring together ideas from the traditionally distinct fields of electrical engineering and ultrafast science. Our approach will enable the creation of next-generation electronic devices that can meet the world’s growing needs for data-intensive, intelligent computing.”

MeV-UED is an instrument of the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) user facility, operated by SLAC on behalf of the DOE Office of Science, which funded this research.

Citation: Sood et al., Science, 16 July 2021 (10.1126/science.abc0652)

Press Office Contact: Manuel Gnida, mgnida@slac.stanford.edu

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.