X-ray Study Reveals Division of Labor in Cell Health Protein

Identical Substructures in 'TH Protein' Couple Two Crucial Cellular Functions

Researchers working in part at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have discovered that a key protein for cell health, which has recently been linked to diabetes, cancer and other diseases, can multitask by having two identical protein parts divide labor.

The TH enzyme, short for transhydrogenase, is a crucial protein for most forms of life. In humans and other higher organisms, it works within mitochondria – tiny, double-hulled oxygen reactors inside cells that help power most cellular processes.

“Despite its importance, TH has been one of the least studied mitochondrial enzymes,” said C. David Stout, a scientist at The Scripps Research Institute whose group led the research. The new study, published Jan. 9 in Science, is an important step toward understanding how this protein manages to perform two crucial cellular tasks at the same time.

Two Crucial Processes

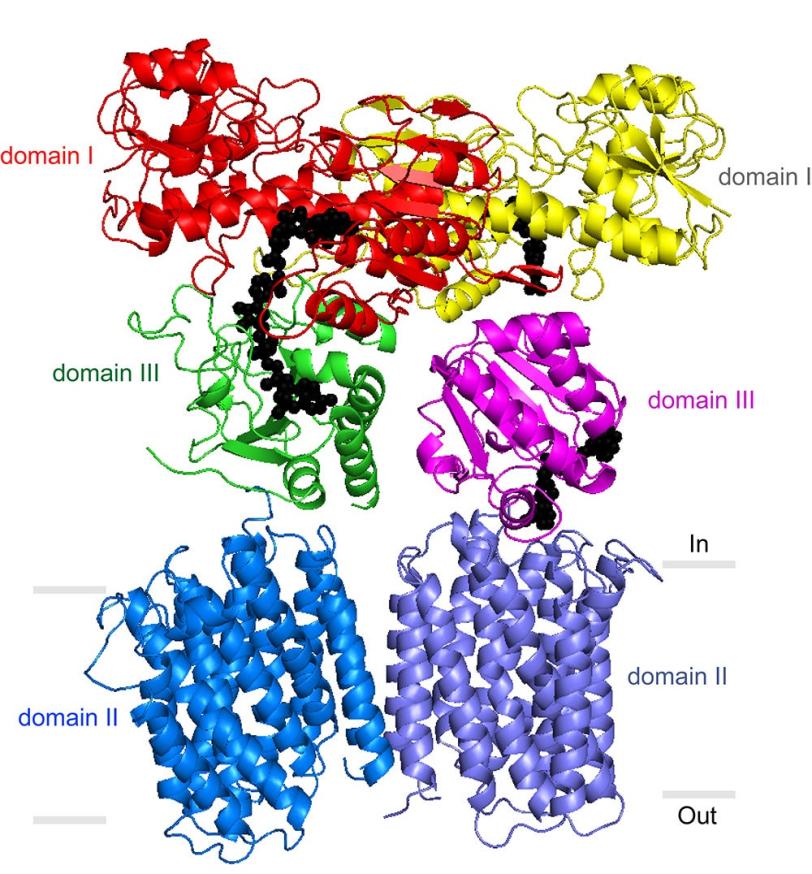

As a mitochondrion burns oxygen, it pumps protons out of its innermost compartment, or matrix. Part of the TH protein extends through the membrane that surrounds the matrix; it allows a one-by-one flow of protons back through the membrane. This proton influx, in turn, is linked to the production of NADPH, a compound crucial for defusing oxygen radicals that are harmful to cells.

But how do TH enzymes couple proton transport and NADPH production? Although Stout’s laboratory and others have previously described portions of the TH enzyme that protrude from the membrane into the mitochondrial matrix, a precise understanding of TH’s mechanism has been elusive. The enzyme has an exceptionally loose structure that makes it hard to evaluate by X-ray crystallography, the standard tool for determining structures of large proteins.

“Key details we’ve been lacking include the structure of TH’s transmembrane portion, and the way in which the parts assemble into the whole enzyme,” said Josephine H. Leung, a graduate student in the Stout laboratory who was the lead author of the new study.

For the first time, the team was now able to determine precise details of the transmembrane portion using X-rays from SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) and Argonne National Laboratory’s Advanced Photon Source (APS), both DOE Office of Science User Facilities. Together with X-ray and electron microscopy data of the whole protein, the study provided major clues as to how TH works.

Flipping Functions

The analysis revealed that two identical copies of TH are bound together in what is called a dimer, and that one copy appears to be involved in proton transport while the other takes part in NADPH production. “Our new study helps clear up some mysteries – suggesting how the enzyme structure might harness protons and indicating that its two sides are able to alternate functions, always staying in balance,” Stout said.

Attached to TH’s transmembrane structure, just inside the mitochondrial matrix, is the “domain III” structure, which binds NADPH’s precursor molecule during NADPH synthesis. Previously, scientists did not understand how two such structures could work side by side in the TH dimer and not interfere with each other’s activity.

The new data suggest that these side-by-side structures are highly flexible and always have different orientations.

“Our most striking finding was that the two domain III structures are not symmetric – one of them faces up while the other faces down,” said Leung.

In particular, one of the structures is apparently oriented to catalyze the production of NADPH, while the other is turned towards the membrane, perhaps to facilitate transit of a proton. The new structural model indicates that with each proton transit, the two domain III structures flip and switch their functions. “We suspect that the passage of the proton is what somehow causes this flipping of the domain III structures,” said Leung.

But much work remains to be done to determine TH’s precise structure and mechanism. For example, the new structural data provide evidence of a likely proton channel in the TH transmembrane region, but show only a closed conformation of that structure. “We suspect that this channel can have another, open conformation that lets the proton pass through, so that’s one of the details we want to study further,” said Leung.

Research funding for the SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program was provided by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Editor’s note: This news feature is based on an earlier news release by The Scripps Research Institute.

Citation: J. H. Leung, et al., Science, 9 January 2015 (10.1126/science.1260451).

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.