Haleh Alimohamadi wins 2024 Spicer Young Investigator Award for breakthroughs in understanding cell membrane activity

Alimohamadi is being recognized for her novel integration of theoretical and experimental results to connect diverse health outcomes with cell membrane behavior.

By Kimberly Hickok

When Haleh Alimohamadi, a mechanical engineer by training, began talking to Gerard Wong about a postdoctoral position in his microbiology and immunology lab at University of California, Los Angeles, Wong was apprehensive. “I had never hired anyone who did not have previous experience doing experiments in my group,” he said.

Alimohamadi had a wealth of experience with computational modeling, but none when it came to experimentation. Despite his initial hesitation, Wong was impressed by Alimohamadi’s persistence and clear, creative ideas and took a chance on the rookie experimentalist, which he now believes “turned out to be one of the best things I did this decade.”

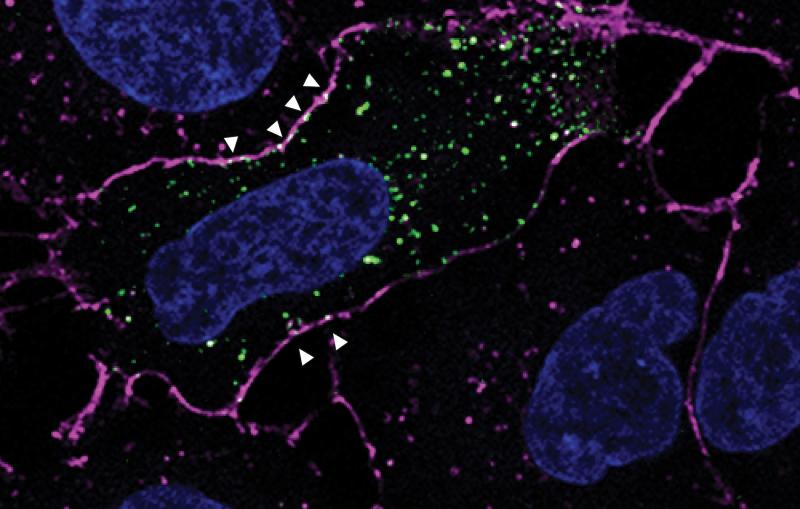

Now, as a bioengineering postdoctoral scholar in Wong’s group, Alimohamadi has leveraged small-angle X-ray scattering measurements at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) to describe in unprecedented scale and accuracy how the exterior membrane of the cells of living organisms responds to various proteins and peptides that come in contact with it. This information is crucial for understanding how pathogens, such as SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, infect and damage cells and cause widespread, lingering symptoms.

For her contributions, Alimohamadi has been awarded SSRL’s 2024 Spicer Young Investigator Award.

“I'm so thankful to the SSRL committee for choosing me,” Alimohamadi said. “It’s amazing to have the opportunity to do this work, especially for a scientist like me, whose background was in a completely different area.”

The shape of life

As a graduate student at the University of California, San Diego, Alimohamadi spent several years developing and analyzing computational models to understand biophysical phenomena at the nanoscale – specifically, how cell membranes can be deformed. But for her postdoc research, “I needed more,” she said. “I needed to manipulate something with my hands and see the events happen with my own eyes, in real life.”

Alimohamadi aimed to join a lab where she could experimentally validate her computational models. “I didn't have any background in doing experiments, neither in physics, nor in biology, but I joined Gerard Wong’s lab at UCLA, and he believed in me and gave me this opportunity,” she said. “That was a big turn in my life.”

Cell membrane-level experiments are at the nanoscale, meaning one-billionth of a meter – or smaller than one millionth of the thickness of a dime. Traditionally, experiments at this scale can be expensive, challenging, or destructive to the cell. For that reason, Alimohamadi aimed to combine biophysical models with SAXS measurements, which don’t destroy the cell.

The results allowed Alimohamadi and her colleagues to describe how the curvature of cell membranes changes in response to specific proteins. From there, the researchers identified the curvature-generating regions of proteins, such as those that are involved in cell death, division, or fusion processes. Understanding how these regions of proteins operate is important, Alimohamadi explained, because disruption in their function can cause several diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic problems and more.

In under two years’ time working with Wong’s group, Alimohamadi has authored and contributed to more than 10 scientific publications in top-tier journals, including a first-authored study published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society in 2023, describing how proteins create pathways, or pores, through cell membranes. Earlier this year, she published another first-authored study in ACS Nano, describing how proteins induce membrane bending and separation processes.

“Learning to do the experiments has been challenging, but I love it,” Alimohamadi said. “This was a big turn in my life and I’m so happy that I took the risk.” As an immigrant, woman scientist, Alimohamadi said she is thankful to all of her mentors for their support.

She also hopes to encourage other scientists considering the shift from theoretical to experimental work to trust their instincts, and make the leap if they want to. “There are going to be several challenges, and you will fail several times, but it’s worth the risk,” she said. “Listen to yourself and do the work that makes you happy.”

The Spicer Award will be presented to Alimohamadi during the 2024 SSRL/LCLS Annual Users' Meeting at SLAC, which will be held September 22-27. The award is named in honor of the late William Spicer, who co-founded what would become SSRL, and his wife Diane.

SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

For questions or comments, contact Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.