Study Reveals 'Bellhops' in Cell Walls Can Double as Hormones

Researchers have discovered that some common messenger molecules in human cells double as hormones when joined to a protein that interacts with DNA.

Researchers have discovered that some common messenger molecules in human cells double as hormones when bound to a protein that interacts with DNA. The finding could bring to light a class of previously unknown hormones and lead to new ways to target diseases – including cancers and a host of hormone-related disorders.

Published in the Oct. 6 edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, these results were made possible, in part, by X-ray experiments at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

"This finding is comparable in its importance to the discovery of how the estrogen hormone triggers activity in human cells, which was key in the development of anti-breast cancer drugs and other hormone treatments," Robert Fletterick, professor of biochemistry and biophysics at University of California, San Francisco, and one of the principal investigators in the study, said.

Resolving a Cellular Mystery

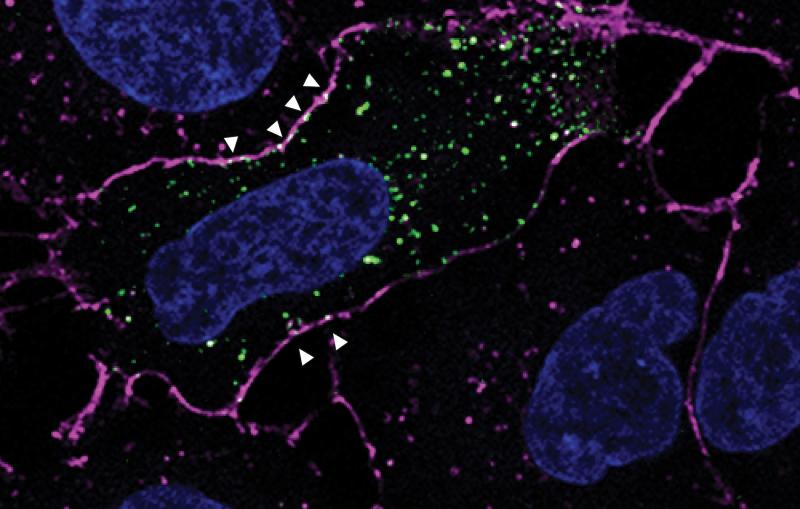

Researchers focused on messengers called signaling phospholipids that act like bellhops in cell walls, escorting proteins to compartments within a cell and activating their functions. The results could explain why these messengers had been observed linked to proteins in the nucleus of cells; their purpose there had been a mystery.

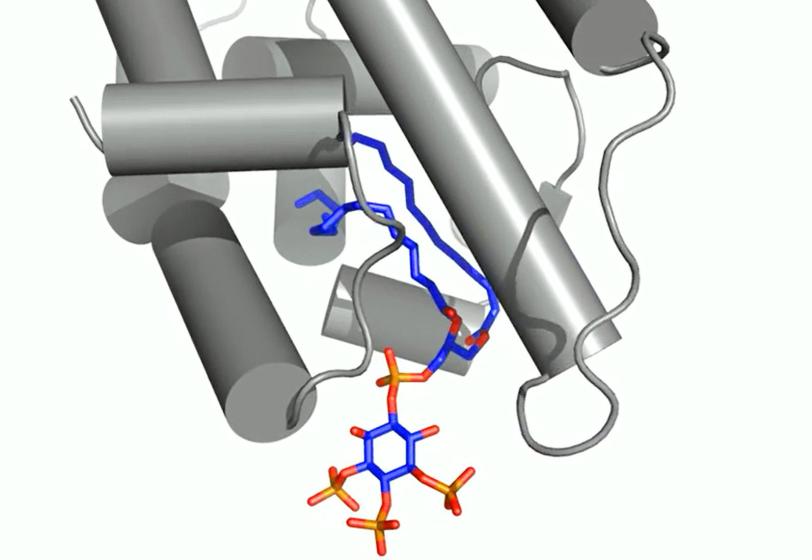

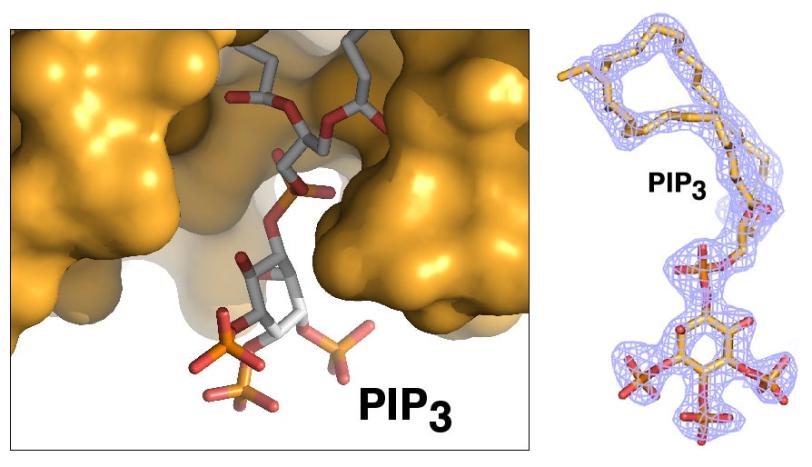

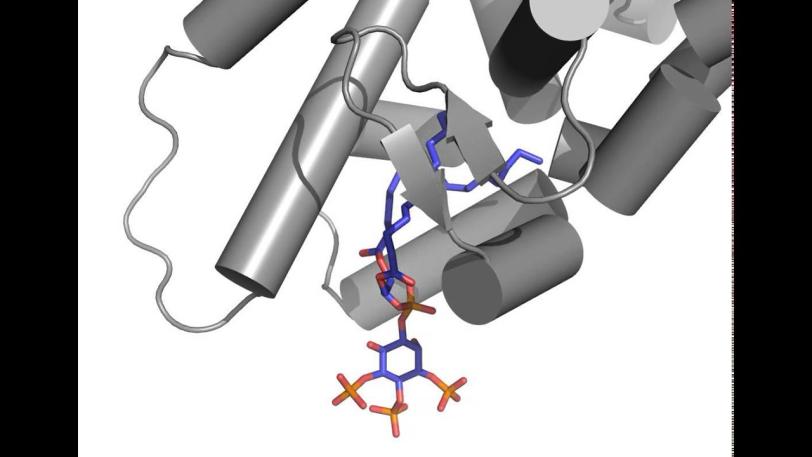

X-ray crystallography at SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, provided the first detailed look at how this messenger acts as a hormone in binding to a specialized hormone-sensing protein called a nuclear receptor.

Phospholipid

These receptors are known to interact with DNA in the cell's nucleus and directly regulate gene expression – a critical mechanism for carrying out the cell’s functions. The experiment focused on a well-studied receptor called SF-1 because its mutations are believed to be associated with infertility and other reproductive disorders, and diseases including colon and pancreatic cancers.

In analyzing X-ray data measured at SSRL, researchers observed how the phospholipids act like hormones when docked into the SF-1 receptors. Hormones are key links in the communications chain between different types of cells and organs that turn on specific genes in cells and activate a broad range of responses.

"The greatest impact of this work might be to prompt scientists to take a new view of phospholipids and what they do in the cell," said Holly A. Ingraham, a UCSF professor who participated in the study.

"The idea that a component of a cell membrane such as a phospholipid could work as a hormone, triggering gene expression, is quite novel,” she said. “People have not really known what their role is in the nucleus. Now we can say for the first time we know why they are there: Some of them might be acting like hormones."

New Details in Bound Biomolecule

Ray Blind, a UCSF postdoctoral researcher who led the study, devoted years of effort to finding a way to prepare crystallized samples of two types of phospholipids that were separately bound to the SF-1 receptor. High-quality crystals were needed to capture high-resolution X-ray data of their contents and determine the structure of the biomolecular complexes.

Debanu Das, a staff scientist at SSRL's Structural Determination Core of the Joint Center for Structural Genomics, oversaw the experiments at SSRL. Based on highly automated X-ray data collection and analysis of about 250 crystal samples, scientists were able to fully map the 3-D atomic-scale structure of the biomolecules, revealing never-before-seen details.

Well-known hormones like estrogen and testosterone bind to and activate receptors by changing their shape. The study found that the phospholipids bind with the receptor protein in a more complex way than classic hormones do, which potentially enables the phospholipids to manipulate the shape of receptors in more profound ways.

The researchers said they hope to design synthetic molecules that can target the disease-associated structures in the receptor protein.

The Joint Center for Structural Genomics is a research consortium that includes SLAC's SSRL; The Scripps Research Institute; the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation; the University of California, San Diego; and the Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute. The joint center is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences’ Protein Structure Initiative (PSI) and the National Institutes of Health. The research was also supported by the PSI-Biology Partnership for Stem Cell Biology. Support for the SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program, whose X-ray facilities enabled the structural work, is provided by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.