[sound]

Stanford University.

Lithium sulfur batteries have a very high

capacity. However, their cycle life is very short so you, you want a battery

that can be cycled multiple times. So you don't want to lose your active sulfur

material so that it can't be reused in the next cycle. Using scanning electron

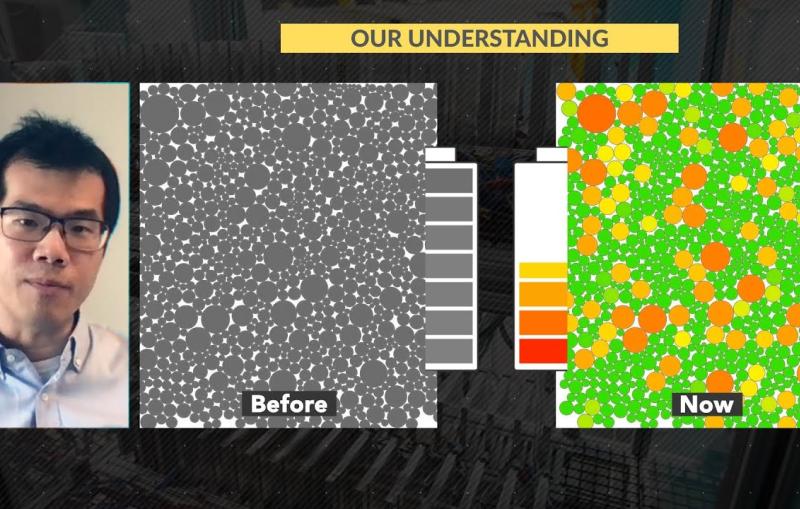

microscopes, previous studies have showed that the sulfur particles that

start out before you start cycling this battery are completely gone by the end of,

of the discharge cycle. But electrons do not penetrate into materials very well,

so you could never look at a full battery in an electron microscope, so we have

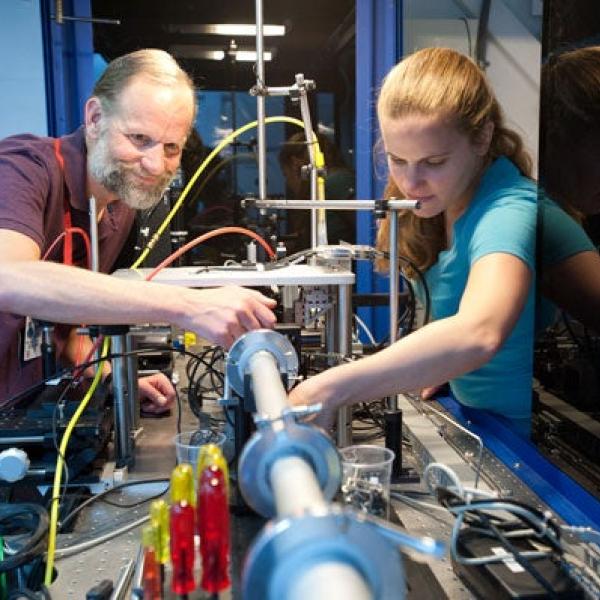

to use x-rays. This is an x-ray microscope. X-rays come from here into the

first lens which is an objective lens. And the objective lens creates an image

which is going to be recorded on our camera or our CCD detector which is far down

there. We were looking at a battery which we put here and we attached

electrode leads off of the battery so that we could cycle the battery while we were

imaging. So, we take images every five minutes and cycle the battery for its discharge

and then charge state. So you can speed up that and, and get a video of what's

happening. In this example in a battery, so what would happen in over eight hours,

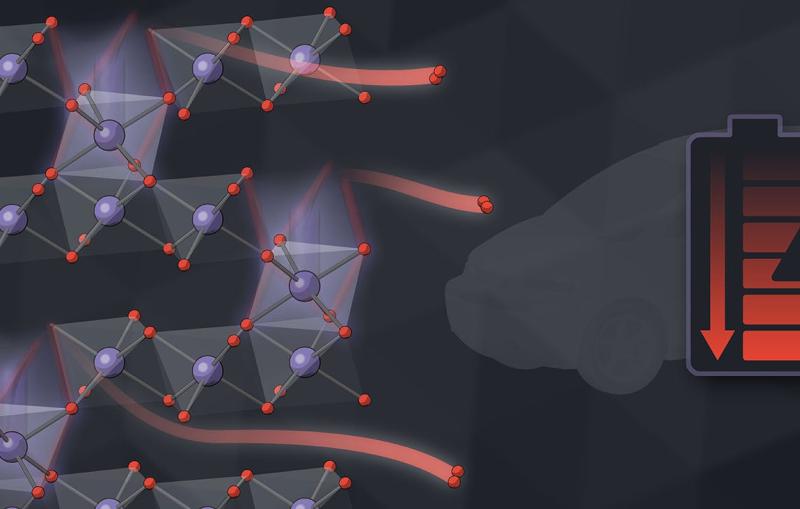

we can make a video in a matter of a minute. What we found, looking at the

battery while it's operating and not having to disassemble it using x-rays

we found that the sulfur particles did not dissolve. That the particles for the most

part stayed where they where for lithium sulfur batteries the significance is

that many scientists and engineers are working on developing ways of

trapping the sulfur In to stay on the electrode. And so this technique can

be used by them to test whether or not their trapping is sufficient enough. You

need a synchrotron to do this very quick imaging in most laboratories.

A single image would take ten minutes for us. A single image takes half a second.

For more, please visit us at stanford.edu.