michael peskin: I welcome you all to the current installment of the SLAC public lectures.

michael peskin: we're very pleased to have today. michael peskin: Justin Miles, who will tell us about really the latest news in our study of the structure of the universe so we're very pleased to have Justin here today um.

michael peskin: You probably know and and you'll find out a lot more about this in this lecture that SLAC as a participant in one of the largest surveys of cosmic structure that have ever been carried out.

michael peskin: we're partners with the other. michael peskin: astronomy groups and also other Department of Energy laboratories, the name of the survey is the dark energy survey you'll hear a lot about it in this lecture um.

michael peskin: Justin was an undergraduate at Yale and came here to SLAC and Stanford to work with the company institute group that's a big part of this dark energy survey collaboration.

michael peskin: So he he's writing his thesis basically on this data, which is both an exercise and kind of a deep dive into the form of the universe, and a big data mining exercise, since the database collected by the survey is truly enormous.

michael peskin: So justin will now tell us about all these things, and I hope you will welcome him, let me just say one more thing before he begins.

michael peskin: you'll see at the bottom of your screen at Q&A box or something to click if you have questions, please type them into the Q&A box.

michael peskin: At the end of the lecture, justin and the two panelists who are also named on this slide will answer your questions and hopefully that will also be a part of this.

michael peskin: event which is interesting to you so once again, please, if you have a question type it into the Q&A box and you may I hope hear it at the end of the lecture.

michael peskin: So, thank you very much for coming and justin please take it away.

Justin Myles: All right, thank you very much, Michael and thanks to everyone who's come. Justin Myles: very excited to be able to talk to you today.

Justin Myles: About. Justin Myles: The tug of war that shapes the universe. Justin Myles: Without further ado i'll sort of just get started, but again just want encourage people to write in their questions for for our group here really excited to be able to talk to you today.

Justin Myles: Alright, so there are three main questions that will talk about in today's lecture the first, is what is modern cosmology what does that mean as a field of science.

Justin Myles: And the second is, then, how does the dark energy survey one experiment within modern cosmology How does it fit into the field of study, and how does it study the universe.

Justin Myles: talk in depth about how we make measurements with telescopes to understand the basic rules governing the universe and we'll we'll finalize the talk, but talking about what is the state of the art we'll look at the, the most recent results and we'll try to understand them.

Justin Myles: So what is modern cosmology and what to do, modern cosmologists do modern cosmology is a part of astronomy, which is often considered the oldest science, in a sense.

Justin Myles: And it is a part of this this field which is differentiated by the sheer amount of data that we can observe today and how that relates to the fundamental rules of physics.

Justin Myles: So one definition, you could you could be given is that cosmology is the study of the origins, the development and the future of the universe.

Justin Myles: As as inferred from observations of the night sky. Justin Myles: So astronomy since time immemorial, has been about looking at the sky and and particularly the night sky to figure out what's going on out there in the world and to figure out our place in the world.

Justin Myles: cosmology focuses on on how the universe has developed, what is this history of the development of the universe, and what is the account of all the objects that are in the universe, and how they interact so it's very closely related with the fundamental laws of physics.

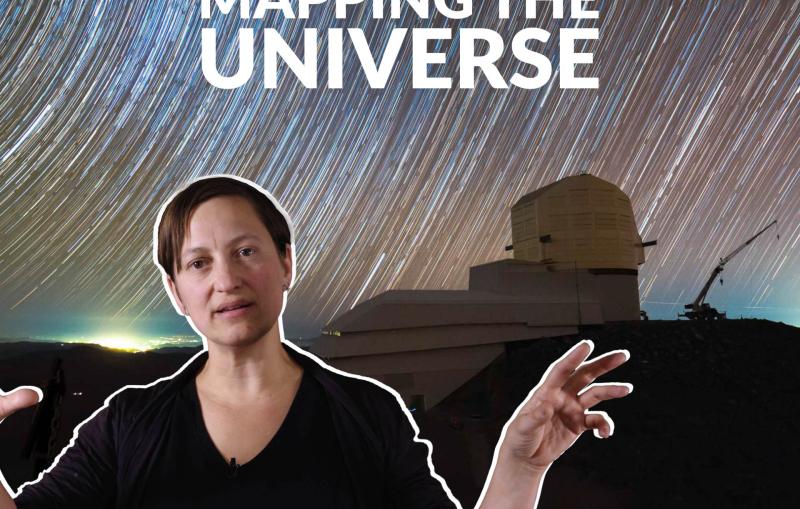

Justin Myles: So what does it cosmologist so i'm very fortunate to be able to work in modern cosmology I am a PhD students graduate student at Stanford university so i'm working on working on my PhD.

Justin Myles: And my day to day involves collecting data with telescopes and analyzing them.

Justin Myles: With specialized algorithms I wanted to give some sense visual sense for what that looks like in the modern world.

Justin Myles: So here's an image of me, working with the telescope, this is the WIYN telescope on the Tohono O'odham Nation and present Arizona

Justin Myles: So modern day telescopes the way they work we don't you know we don't look through an eyeglass we have we they're hooked up to advanced cameras.

Justin Myles: And here, you see all the things we might want to interact with while we're collecting observations.

Justin Myles: So we were tracking objects that we want to look at in the sky, as they move because of the earth's rotation.

Justin Myles: we're looking at the camera in particular we're looking at the positions of fiber optic cables that are picking up light from individual galaxies as well as looking at whether and how the telescope itself, which is a complex machine in its on its own, how its operating.

Justin Myles: So I thought it might be helpful to think about a historical analogy so.

Justin Myles: Human accounts of all the elements of the universe have changed over time and there are many such accounts in history of many different cultures, I have here an image of one particular account.

Justin Myles: This is known as the the Ptolemaic model from Ancient Greece and the reason I wanted to pick This is because it has so few objects it's something you can serve wrap your head around in this this picture just depicts.

Justin Myles: One understanding of all the stuff in the universe earth there's some of the other planets and there's an edge, and that was it.

Justin Myles: And I think this is helpful to think about, because it really did explain, many of the observations that were.

Justin Myles: possible with the naked eye right people could tell that the way the planets moved it's not necessarily exactly the same as the way the stars move in the sky, but the way the planets look is not exactly the same so.

Justin Myles: We should always stay grounded and when we're thinking about these problems in that they're that they're related to what we see in the sky and trying to explain it.

Justin Myles: But, of course, our understanding has evolved quite a bit over over the years and it's evolved in large part due to.

Justin Myles: An increase in what we can see because of improvements in telescopes and both in their size and their sophistication so here's an image collected by the hubble space telescope telescope, which is a satellite.

Justin Myles: And what you're seeing here is a deep image of a tiny patch the sky, called the hubble deep field.

Justin Myles: So in this image this it looks very different from what you'd see with the naked eye each of the specs you see here is a distant galaxy it's a galaxy apart from our own Milky Way.

Justin Myles: And you see a huge number of these galaxies and a wide variety and color shape and size, because some of these are closer and further visit there's a huge variety of what you're seeing here.

Justin Myles: Modern cosmology on one one large part of modern cosmology is using observations of galaxies like this and huge numbers of these observations, in order to understand the basic rules of the universe.

Justin Myles: So let's talk about the modern cosmological model, so it starts, as many people will know with a hot big bang.

Justin Myles: So it's a big bang that's the start of this story and then immediately afterward the universe is expanding and becoming larger but it's very hot and smooth so it's just as it's called a primordial soup of all the stuff in the universe.

Justin Myles: And as the universe expands it cools and what plays out in this cooling is that to gravity can then gravity is an attractive force where matter attracts other matter, it can then form structures, it can get clumpyer.

Justin Myles: So that's what's happening as the universe is cooling and expanding that structures can eventually be allowed to form.

Justin Myles: So the universe starts out as hot and smooth and over the course of more than 13 billion years it becomes colder and clumpyer.

Justin Myles: So, if you look at the to the edges of this diagram you see in the early universe, this is hot soup where everything is sort of the same and it's very different from the present day universe, when we look out, we see.

Justin Myles: regions where there's a lot of matter like galaxies and then regions where there's really nothing at all it's much it's cold and empty cold voids.

Justin Myles: So that's the the history of how the universe has developed so you can already see.

Justin Myles: That there's this tension between the the expansion of the universe and gravity. Justin Myles: gravity tending to form structures by pulling things inward and expansion of the universe, because space itself is stretching which tends to suppress suppress that formation of structure.

Justin Myles: There are other parts of the story of course there are exploding stars there's weird things in space which dump energy in a sense, out into their environments, but in the largest scales this story is what tends to determine what the universe looks like.

Justin Myles: So with that basic understanding now i'm going to talk about what are the problems that we're stuck on because we think this story is very successful in many ways, but also merits additional scrutiny and verification.

Justin Myles: So the first thing I want to talk about us being stuck on what are the nature of dark matter and dark energy So these are two components really important components of the universe.

Justin Myles: The actual the name for the modern cosmological model is Lambda CDM.

Justin Myles: The Lambda stands for a particular kind of something that can be interpreted as a dark energy and the CD m stands for cold dark matter So these are really important components Where do they fit.

Justin Myles: All right, so this cupcake represents all the stuff in the universe, something we call it the energy budget how much of the energy in the universe, is a particular thing.

Justin Myles: The stuff we're familiar with all the atoms in the universe, that everything that's making up the stars and the planets asteroids gas dust all of that those are just the sprinkles on this cupcake this ordinary matters actually a very small amount to be energy budget to the universe.

Justin Myles: Most of the matter is actually something we call dark matter it's called dark matter because it must not interact very strongly with light it's it's not easy to see if it does interact with light at all.

Justin Myles: And when I say that it can be more than one thing, but in general refer to dark matter is at least one thing that we can't see in a normal way.

Justin Myles: The evidence for dark matter is stretches back decades so there's a huge amount of evidence in favor of the existence of.

Justin Myles: Some form form or forms of dark matter, one of the more intuitive explanations, is that we can measure the speeds of objects in space as they move.

Justin Myles: and things will orbit around centers of gravity so, for example, the stars in the galaxy will orbit around the Center of the galaxy.

Justin Myles: The galaxies in a cluster of galaxies or orbit around the the Center of gravity of that system, and when we observe the speeds of those objects, as they whip around the Center of their system.

Justin Myles: The speeds are really, really fast, and when you add up all the the mass that's holding it in with by gravity it doesn't add up it's not enough to hold these things in given how fast they're moving, so there must be some some other matter that we can't see to hold everything together.

Justin Myles: So that's most of the matter that accounts for much more of the energy budget than the ordinary matter and then there's another component, which is actually.

Justin Myles: More mysterious and more recent at least observationally which we're calling dark energy, and this is something that we have introduced because.

Justin Myles: introduced to our model because the expansion of the universe, it turns out, is accelerating.

Justin Myles: And we need an explanation, we need some cause for that acceleration and there are ways to accommodate that in the laws of physics and.

Justin Myles: Because this is a something that can be interpreted as a form of energy and the way that it can be introduced in the equations but it's also something that we.

Justin Myles: don't really see in an ordinary sense it's called dark energy so that's actually the most of this cupcake, so we need to better understand the nature of dark matter and dark energy.

Justin Myles: The evidence for the existence of these things is compelling but we don't have an excellent description of how they operate in the way that we do for all the ordinary matter that we've been working on for much longer.

Justin Myles: So let's talk a little bit more in detail about this so dark matter as i've said, we have quite a bit of evidence for the existence of dark matter.

Justin Myles: But we don't know what it is, in the sense that we know what, for example, electrons are we can't give an exact description of what it is and again, it can be more than one thing.

Justin Myles: So here's a venn diagram this is super complicated there's no need to look at each individual element of this venn diagram, but this is.

Justin Myles: This is illustrating all the different theories of dark matter that they're there are and we're we have many experiments here on earth trying to detect this dark matter.

Justin Myles: But we still just don't know so the point is that we want to better understand from all kinds of observations dark matter in order to figure out exactly what it is.

Justin Myles: And now let's talk about dark energy and the expansion of the universe so keeping with our theme of baked goods here now, we have.

Justin Myles: raisin bread okay so there's an image in the bottom illustrates a raisin bread before and after it's baked so the left hand side you see.

Justin Myles: A lump of dough and the right hand side you see the baked baked bread and each of the black dots represents raisins in the raisin bread.

Justin Myles: or galaxies in the universe Okay, as the as the dough bakes as the bread bakes it expands, and so what you'll notice is the distance between each of the either raisins and the raisin bread.

Justin Myles: The distance between them increases after you have after you've baked it right every every raisin and as farther away from every other raisin

Justin Myles: compared to when it was first baked or when it was not baked, so this is an analogy for the galaxies in the universe, we see something similar playing out when we observe galaxies in the universe, all the galaxies are moving farther away from each other, essentially.

Justin Myles: So this is how we can measure the expansion of the universe, because we can measure the velocities of things in space and the positions of things in space.

Justin Myles: So this is something that we are we're stuck on and we're working on understand and we want to measure this very directly and something that we we care a lot about in modern cosmology.

Justin Myles: So now, you should have a better intuition for the title of this talk there's a there's a tug of war between the gravitational effects of dark matter and dark energy and this tug of war, it determines how clumpy the universe is.

Justin Myles: On one hand we have the inward pull of gravity where dark matter being the dominant form of matter is going to form structures.

Justin Myles: And on the other hand we have the stretching of space itself accelerated by dark energy which tends to suppress the formation of structures essentially pull structures apart because space itself is stretching.

Justin Myles: So we want to measure this very directly. Justin Myles: we care about exactly how clumpy the universe, is because it tells us how this tug of war is playing out.

Justin Myles: Right now that's qualitative but i'll try to give a bit more detail about how we quantitatively talk about clumpiness but that's the big idea of what dark energy surveys measuring primarily.

Justin Myles: Alright, so let's look at some data about how that looks, so this is an image of different data is the sloan digital sky survey in this image every point every colorful point represents the galaxy okay.

Justin Myles: And the Center represents, where we are, as you get further away from the Center we're looking at galaxies that are further away from us.

Justin Myles: There are two other directions, you can look at one of those directions we've squashed over and the other direction is the.

Justin Myles: angle on the circle so clockwise or counterclockwise in the circle.

Justin Myles: So what you'll notice is the galaxies are not uniformly distributed it doesn't look, for example, like those of us who are old enough to know what TV static looks like it doesn't look like that.

Justin Myles: Instead, you see some parts there's a lot more galaxies other parts, there are these cold voids this is a, this is a qualitative description of how clumpy the universe is by just mapping galaxies in space we have an understanding how clumpy the universe is.

Justin Myles: Now there's another method, we can make, which is really interesting so now we're going far we're going back in time to the very early universe.

Justin Myles: Just 300,000 years after the big bang, so this is very early universe, and what i'm showing here is the oldest light in the universe, this is the oldest light that's you know streamed out and can still be observed today it's really everywhere.

Justin Myles: The the map is an oval because i'm representing an entire sphere and 2d plane so you're seeing your screen is flat, and I want to represent the whole sphere so.

Justin Myles: In order to do that, we have to distort the sphere in some way, this is just a distortion of that sphere, so you can see the whole sphere, but looking at everywhere in this in the sky.

Justin Myles: And this light is this can light can't be seen by the human eye, but it can be detected with telescopes and picked up by specialized cameras.

Justin Myles: So here what you're looking at what the color represents in this map is the temperature of the source of that oldest light.

Justin Myles: And so you see that they're blue regions colder regions and their regions, which are warmer regions, so you see that even in the early universe 300,000 years of the big bang it wasn't perfectly uniform and temperature.

Justin Myles: Now, an important feature here is that the temperature scale is very, very, very tiny, so this temperature scale is showing very tiny differences in temperature mostly it is actually basically the same temperature.

Justin Myles: But the scale here the units of this are millionths of a degree so very tiny differences in temperature, which we have worked over many decades to be able to measure precisely.

Justin Myles: But you'll notice that this is actually apparently less clumpy than the late universe image we saw and when we looked at the galaxies there were some regions, which were.

Justin Myles: which were more obviously not random where's this field appears to be a little bit more random.

Justin Myles: So this brings us to a really important idea is that we want to, we want to model, which explains both of these images.

Justin Myles: they're very different times in the universe, one is very early in the universe, you know there's very late. Justin Myles: they're very different kinds of data, one is looking at to the oldest light in the universe, the other is looking at for the positions of galaxies, for example.

Justin Myles: But we want a story that ties together these observations, and this is what we're working on actively doing tying together all of these observations.

Justin Myles: And at this point is probably worth mentioning that, so our modern cosmological model, as you can now see it doesn't just.

Justin Myles: explain the observations of the galaxies in the sky it explains many, many different kinds of observations so modern cosmology has we observe light of all wavelengths not just what the human eye can see.

Justin Myles: it's very closely connected to fundamental physics and we're trying to tell a story which incorporates all of these things.

Justin Myles: That said, another piece of context is that this interesting story between the nature of dark matter and dark energy and how it affects the structure of the universe.

Justin Myles: it's an important big question about the universe, but I want to be clear that it's not the only mystery in physics, so it can seem sometimes like this is this is everything there, there are many other mysteries and physics, but this is one big field of inquiry that were engaged in.

Justin Myles: Alright, so now coming back to our diagram for the history of the universe, we want to be able to.

Justin Myles: observe the oldest light in the universe cause the called the cosmic microwave background and then also measure the late universe, the galaxies that we see nearby us and tell a story that.

Justin Myles: can explain both and explain how you get from one to the other, because we know the clumpiness is changing, so we want to be able to quantitatively describe exactly how much that's happening.

Justin Myles: So that's the context that's the the big idea that we're trying to investigate and now i'm going to talk about.

Justin Myles: How we do that, in practice, so we're going to switch gears here, so now we're going to be interested in how do we actually collect data to do that, and what are the challenges to collecting those data.

Justin Myles: Which, of which there are many and many scientists work for their entire careers on one particular challenge, because these are such complicated experiments, we want to do so, the experiment i'll be talking about it's called the dark energy survey.

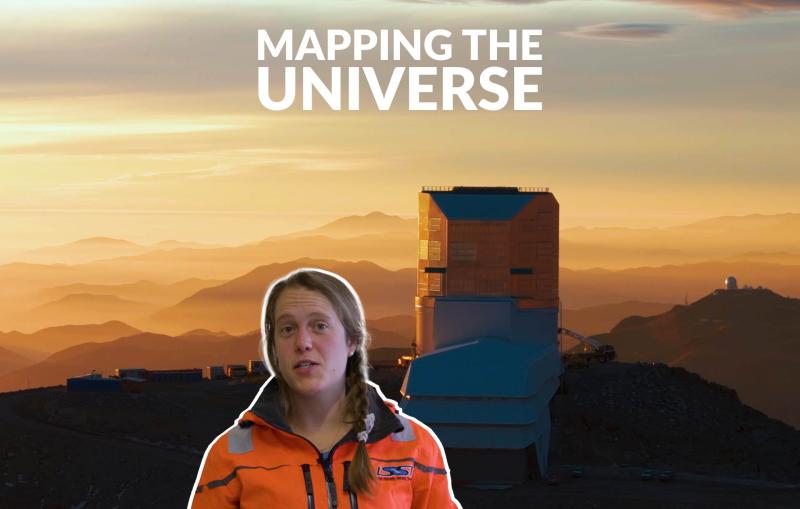

Justin Myles: So let's think about building building a cosmological experiment, we need a telescope and the first thing we need to do is figure out where we want to put it.

Justin Myles: So here, you see an image for the dark energy survey telescope is put the Cerro Tololo telescope.

Justin Myles: So this is in a desert and Chile it's the driest place in the world that's because it's situated between these two mountain ranges which essentially blackout.

Justin Myles: blackout moisture from entering so that's really good because it makes the the atmosphere, stable and that's what we want, when we're observing things from space.

Justin Myles: That also means there'll be less nights covered with clouds because astronomers still have to deal with cloud cover that ruins data.

Justin Myles: In addition, it's far from where lots of people live so they'll be less light pollution, in fact, affecting our data and also we observe.

Justin Myles: At our top at our observatories in general astronomers observe light of all wavelengths which stretches not just not just what we can see, but stretches to the radio waves, for example, and radio waves interference from.

Justin Myles: Human telecommunications interference as well, so this isolated dry site is really perfect.

Justin Myles: And one thing just looking at this image you'll notice is that. Justin Myles: The Dome is closed and there's a window, which will open when it's nighttime so that we can observe and you also see that there's these windows, essentially in the Dome.

Justin Myles: Those have been opened, even though the sun is up because they want to equilibrate the temperature inside the Dome with the outdoor temperature.

Justin Myles: that's because temperature differences can lead to turbulence atmospheric turbulence, essentially, and you just want everything perfectly still as much as possible.

Justin Myles: Then you need a big telescope, so we are interested in observing as many galaxies as possible, and that means we want observe very faint very distant galaxies in order to do that we need to collect as much light as possible.

Justin Myles: The theme for how to understand how we do that is that think of telescopes as buckets for light.

Justin Myles: You think of a telescope is a bucket for light in a way that a bucket might collect rainwater then it becomes clear why you wanted to just be bigger, the bigger the telescope the more light, you can collect, so our telescope is four meters from end to end in diameter and.

Justin Myles: This is it's it's important to it's important to collect as light as much light as possible.

Justin Myles: The other thing you need is a very big camera and a very advanced camera, so there are important differences between.

Justin Myles: The the cameras we use an astronomy and the cameras that you might be familiar with from your day to day life so one is that it's much bigger so here, for example, you see the dark energy camera.

Justin Myles: constructed from 2008 to 2011 it says 570 million pixels that's what 570 megapixel means and each of those pixels is 15 microns by 15 microns.

Justin Myles: don't expect you to know how small, that is, but for comparison, the iPhone four came out in 20 2010 the pixel sizes were much smaller 1.75 micron by 1.75 microns so each of these pixels is large, and there are many, many more because iPhone had just 5 million pixels compared our 570.

Justin Myles: This camera is 44 centimeters across that's about 17 inches. Justin Myles: And another important difference here is that we're interested in detecting very, very faint light.

Justin Myles: So that the silicon wafers the chips, in a sense that we're using to collect those lines that you see here, these chips they're thicker because we want to collect.

Justin Myles: We want when a light particle hits it we want there to be more of a chance for to interact with the metal and get detected and get converted to.

Justin Myles: An electrical signal that we can pick up that it's also important because we care about very red galaxies and red lights have lower energy, so we need a thick camera chip, excuse me.

Justin Myles: In order to in order to detect as much of those red light particles as possible.

Justin Myles: So the bottom left you see one image from the dark energy camera cam and the Green there's a tiny green tiny green like point that's the size of the iPhone four camera at the time.

Justin Myles: So we've talked about a big telescope and big camera The next thing is a big survey so remember that we're interested in understanding how clumpy the universe is.

Justin Myles: So if I gave you observations of two galaxies you know, obviously not be able to say how clumpy the universe is, it just is not the right data.

Justin Myles: So that gives you a sense that we're interested in a statistical measurement of huge numbers of galaxies without huge numbers of galaxies you can't do.

Justin Myles: The kind of science we're interested in any particular galaxy doesn't tell us about the nature of dark matter and dark energy it's only an ensemble of a huge number of galaxies that can do that.

Justin Myles: So you want to a big survey dark energy survey is shown here it's did about a six of us an excuse me an eighth of the sky.

Justin Myles: over six years and within the first three years of data alone we have good measurements good measures of position and shape for over 100 million galaxies the raw images is over 100 terabytes of data.

Justin Myles: And one thing to point out here is the shape of this survey Just to give you a sense for how astronomers think and why it looks sort of random.

Justin Myles: Is that we want to be able to combine our data with other other telescopes which observe different kinds of light as.

Justin Myles: as well, and that gives us more power so you're seeing a weird shape because we've designed to shape that's going to.

Justin Myles: overlap with other kinds of telescopes which are maybe not in Chile and the southern hemisphere, but, at the very edge in the northern hemisphere so it's easier to see.

Justin Myles: And we're also want to avoid certain parts of the skies enable the Milky Way plane is a lot of stars and dust and that's going to make it harder for us to see our really faint.

Justin Myles: galaxies that we're particularly interested in so every little detail here has been designed for a particular kind of science, and this is actually something that's an evolution in astronomy that we've designed this long term experiment to to specifically achieve one goal.

Justin Myles: Among others.

Justin Myles: So big telescope big camera big survey a big data that means you need a big collaboration, so the dark energy survey is a project with over 400 scientists working on many things, not just the.

Justin Myles: The experiment that i'm describing today, because there are many other things you can do with the data. Justin Myles: But this is a kind of project which is doable only with a large team, so we have an international team.

Justin Myles: With many people, including many, many people right in college and right after right after college, as well as well as more senior.

Justin Myles: Scientists all working together to achieve this common goal, so one thing worth knowing is that, in order to achieve this goal, requires people who can.

Justin Myles: engineer good machines and develop innovative things like cameras, as well as work with advancing algorithms for processing and analyzing data and understanding how those data, then relate to.

Justin Myles: The the underlying scientific theory that we're trying to understand so there's a lot of variety in what people in the dark energy survey do.

Justin Myles: So that gives you a sense for how the dark energy survey operates now let's talk about some of the scientific principles that relies on and the kinds of measurements it's trying to do.

Justin Myles: In order to do that we need to understand gravitational lensing, so this is something which is predicted by einstein's theory of gravity.

Justin Myles: And it says basically that gravity can be thought of as the curvature of space itself, which is due to the presence of energy and matter.

Justin Myles: So here in this diagram you see in the in the distance there's three galaxy shapes and thelight from those galaxy shapes is going to pass through space to get to us and along that path we've put into clumps of dark matter that's what those two circles represent.

Justin Myles: Those clumps of dark matter will bend space itself, this is, this is a result of the theory of gravity.

Justin Myles: And because it bends the space itself that light will be reflected, so the shape that you ultimately observe will be different, so if we just look at each individual shape in the background, then compare it to the shape of the end of the arrow it's been sheered the shape has been altered.

Justin Myles: We want to observe this so already, you can see if the the presence of matter.

Justin Myles: changes the shapes of distant galaxies then measurements of the shapes of galaxies can be used to understand what the distribution of matter that it pastor was that's that's one of the key principles that the dark energy survey relies on.

Justin Myles: So here's an analogy, I like to make so here service without the so the text in the bottom on the right says, this is not a galaxy cluster i'll be covering it now.

Justin Myles: On the left hand side there's a painting by René Magritte it says in French, this is not a pipe but it's clearly an image of pipe.

Justin Myles: The purpose of or the the idea here being that the pipe and the image of the pipe are two distinct things and that's also true in.

Justin Myles: Our images of the sky so we're looking at as an image of a galaxy cluster so each of these yellow bright yellow blobs those are galaxies in the galaxy cluster.

Justin Myles: But if you look really closely you'll see that there's also these circular looking arcs so these circular looking arcs are not galaxies in the galaxy cluster they're actually galaxies behind the galaxy cluster.

Justin Myles: And because the galaxy cluster is so massive it's changed the shape of the galaxies so much that they just appear as tangential arcs circular arcs.

Justin Myles: So this is showing you directly in the data how the presence of matter changes the shapes what we see and how we care about understanding these distortions themselves they're a new form of information we're detecting.

Justin Myles: So now we can talk and specifically about what the dark energy survey measures. Justin Myles: As i've said we care about doing statistical measurements of structure in the universe from images of galaxies that's what we can see, we can see the galaxies we can't see the dark matter.

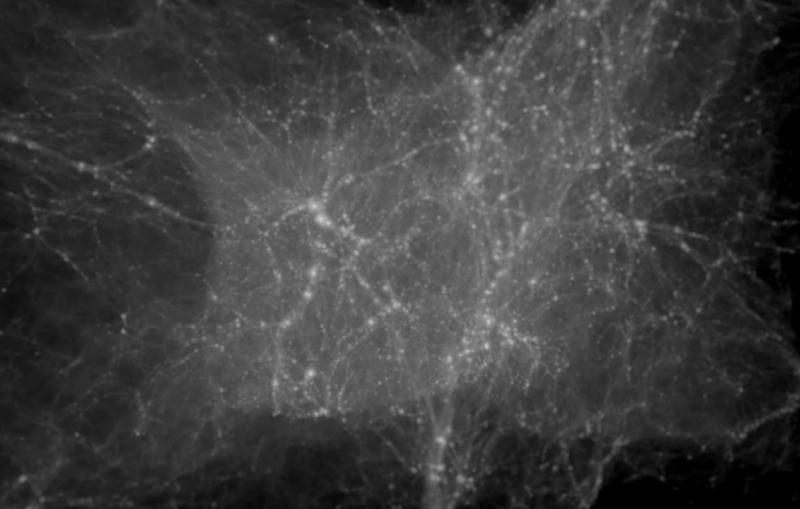

Justin Myles: But we want to understand what the distribution of the dark matter is so, how do we do that, so in this diagram at the top, you see.

Justin Myles: square in that square there's a distribution of dark matter it's this web that it's formed we don't know what that is in real life that is done in a computer simulation okay so we've simulated what the distribution of dark matter is and how it has evolved.

Justin Myles: On top of that web is a web of galaxies the web of galaxies largely traces the web of dark matter and we can see the galaxies.

Justin Myles: So one of the ways we can understand the distribution of dark matter is to just understand the distribution of the galaxies that's.

Justin Myles: Point number one here galaxy clustering on the left, we can measure how clustered galaxies are the quantitative way of saying that is.

Justin Myles: How likely, are you to find a pair of galaxies separated by particular angle as a function of that angle small angle large angle.

Justin Myles: That is a quantitative statement that likelihood and that tells you exactly how clumpy the galaxies are which is related to how clumpy the dark matters so that's The first way, we can understand the underlying distribution of dark matter that we can't see directly.

Justin Myles: The other way is depends not on the positions of the galaxies but on the shapes of the galaxies that's number two called cosmic shear.

Justin Myles: Now, instead of looking at how likely we are to find a pair of galaxies separated by a particular distance were saying how related are the shapes of galaxies separated by a particular distance how likely, are they to be related.

Justin Myles: This is telling you also about the distribution of dark matter, because as i've said the shapes of those galaxies are sheared their altered by the dark matter that they had to pass through to get to us.

Justin Myles: So we can use, not just the position, but also the shapes to understand the distribution of dark matter cosmic shear.

Justin Myles: The third is just a combination of position information with shape information here you look at the correlation.

Justin Myles: How the relationship between the shapes of distant background galaxies and the positions of nearby foreground galaxies it combines the information.

Justin Myles: So these are three different kinds of measurements, we can make all the same data and we combine them, this is an statistical advance in some sense that we're combining data from the same underlying.

Justin Myles: The same underlying truth but different kinds of data in order to maximize how much information we extract from the data.

Justin Myles: So that's the kind of measuring want to make, but unfortunately it's extremely challenging and I want to talk in detail about what these challenges are, of which there are many.

Justin Myles: Because the cartoon to help us understand that so we're going to talk about all the things that happened to the image of the galaxy.

Justin Myles: let's start from Upper left here you have a cartoon of this of the sheep and.

Justin Myles: This is what it looks like but as i've said that image is going to be shared it's going to be distorted due to gravitational lensing so that moves us one panel to the right its shape has been changed.

Justin Myles: That that's not the only thing that's happened, though the light has also had to pass through the earth's atmosphere. Justin Myles: And there was atmospheres turbulent Is anyone who's been an airplane those that turbulence also bends the shape of the light so that's going to that's something we call the point spread function or PSF as its shown here and that's also going to change the image.

Justin Myles: that's not it then once the lights passed through the. Justin Myles: Through the the atmosphere and gone through the telescope hit the mirrors and whatnot then it hits an actual camera, which is actually has this individual pixels the image we see is actually pixelized because we have no other choice.

Justin Myles: The process of converting that light those light particles to electrical signals that we can then interpret with computers that's a noisy process it's not a perfect one to one.

Justin Myles: correlation so there's an additional noise and uncertainty that will be introduced by that process so that's going to further change our image.

Justin Myles: And then finally we've only considered a case where there's one individual thing we're looking at, but in reality galaxies the images they can be overlapping that can be blended because one galaxy.

Justin Myles: When you one galaxy behind another galaxy they can be overlapping largely overlapping and we want, we don't want to throw away all those data, so we also want to understand what happens when data when we have galaxies images that are blended.

Justin Myles: This just gives you some idea of an account for how just how many effects, there are that we need to account for each of these each of these issues is dealt with by whole teams of scientists.

Justin Myles: So with that i'm going to talk a little bit more about something that I work on very directly we've talked about gravitational lensing.

Justin Myles: Which is very analogous to lensing you'd see with a magnifying glass or any kind of anything that bends light, water, even here let's think about.

Justin Myles: let's think about how lensing depends on distance, so therefore images here, which represent for different moments in time.

Justin Myles: And there's a piece of paper showing graph paper where there's a straight grid square grid ground on it drawn on that piece of paper.

Justin Myles: And what you're looking at is you're looking through a wine glass at the base of the wine glass there the stem at the base of that wine glass.

Justin Myles: The glass itself is going to bend light and, as you pull that one glass away from the paper and then put it back down you see that the amount of bending it does changes.

Justin Myles: So the amount of distortion, we see it does it just depend on the fact that there's a wine glass there, it also depends on where that wine glass is where the lens is relative to the source and the observer.

Justin Myles: This means that if we want to interpret the change in the shapes of galaxies due to gravitational lensing, we also need to understand, to some extent the distances between us and the lens got lens matter and us and the distant galaxies.

Justin Myles: This is this turns out to be really challenging, so this is in some sense the elephant in the room.

Justin Myles: it's that if we want to interpret the sheer measurements of the galaxy shapes, we also need to have some constraints on what the distances to the galaxies are.

Justin Myles: So what would that look like if we to know that that would look like a plot like this, this is a an illustration of what the data would look like.

Justin Myles: On the horizontal axis represents the galaxy distance so things that are closer to the left hand side would be galaxies that are closer to us things on the right hand side would be galaxies that are further away.

Justin Myles: And the vertical axis the y axis would represent how many galaxies had that particular distance so there's a curve here, which represents how many galaxies do you have at a particular distance as a function of that distance.

Justin Myles: This is the kind of this is the diagram you want to draw because, if we can draw this, then we can interpret our sheer measurements how the galaxy shapes have been altered.

Justin Myles: But how do we do that think about think about this, if you just take a picture of something, how do you know how big it is, if you don't know intrinsically how large something is.

Justin Myles: it's a challenging thing and we rely on this principle that have come up with the mnemonic for which objects in mirror or bluer than they appear.

Justin Myles: So we can understand galaxy distance in fact by understanding the galaxy color let's talk about why that is so in the top diagram you see.

Justin Myles: A wave of light that wave is let's let's call this blue light Okay, and at the also is represented the length of the universe at a particular time when that light is emitted.

Justin Myles: But as i've said the universe is expanding so because the universe is expanding the space itself is is expanding.

Justin Myles: The wave that is also going to get stretched out and when that wave of stretched out that's changing the wavelength, of the light, so the wavelength, the distance between each peak here.

Justin Myles: that's getting larger, and that means that the light is actually going to be redder, this is a key principle that we can rely on galaxies appear.

Justin Myles: appear redder than they really are so they're bluer than they appear, and we want to measure how much better galaxies appear in order to have that's our proxy for distance is what we're going to treat as our distance it works for our experiment.

Justin Myles: So that's the measurement context, this is the kind of measurement want to do we want to measure galaxies shapes positions and we want to use their colors to better understand the distances with that we can dive in to the state of the art.

Justin Myles: Alright, so we talked about the elephant in the room, just measuring galaxy distances, I wanted to spend some time talking about this, because this is what I do in particular.

Justin Myles: And this is the first time we'll be seeing plots of how scientists look at data, I wanted to give.

Justin Myles: spend some time talking about how scientists what scientists look at and we're looking at data to give you a sense for how we think about.

Justin Myles: Interpreting data and how we communicate with each other, we tried to simplify these diagrams to make them more accessible as well, so with that there's a quote here grown ups love figures and it is very true.

Justin Myles: So here on the horizontal axis instead of galaxy distance we have galaxy redshift because I told you how much redder it appears that's in some sense a measure of its distance.

Justin Myles: And the y axis again we have number of galaxies and i'm showing the measurements, we did for the dark energy survey.

Justin Myles: Each of those symbols represents a group of galaxies How does that work where the symbol is on the horizontal axis how far it is from left to right that tells you how far away, is that group of galaxies.

Justin Myles: So that's one thing, whereas it on the horizontal axis The other thing is, whereas on the vertical axis, that means how many galaxies are in that group of how are in that group of galaxies so things that are further up there are more galaxies in those groups.

Justin Myles: And then there's one more thing I could have just drawn points here to represent those groups of galaxies but I didn't Instead, what we have here.

Justin Myles: Are symbols and the symbols represent they tell you that we don't actually know exactly what the truth is, instead, we can tell you the truth is about this plus or minus this.

Justin Myles: And the symbols where it's wider, is where we think it's more likely to be in for every particular group of galaxies and where it's narrower that's where it's less likely to be for any particular group of galaxies.

Justin Myles: So this is our measurement of the distribution of galaxy redshift, which is our proxy for galaxy distance.

Justin Myles: With that, we can see the essential that's invisible to the eye, we can interpret our shear measurements and get a map for dark matter in the universe.

Justin Myles: here's the what that map looks like so again you're seeing the whole Sky, which is a sphere and it's just distorted in a way that makes it look like an oval.

Justin Myles: And this, the shape, with all the the purplish color, that is, the dark energy survey map of dark matter in the sky, the darker points are where there's less dark matter the lighter points of where there's more dark matter.

Justin Myles: you'll see again that we're avoiding the the plane of the Milky Way because that has all the dust and stars it's just going to interfere with us measuring really faint distant galaxies.

Justin Myles: So now let's talk about another measurement galaxy clustering remember how you described this this was how likely, are you to find a pair of galaxies separated by a particular distance as a function of that distance.

Justin Myles: let's break that down this is, this is what that looks like to to the scientists. Justin Myles: So here the horizontal axis that tells you what's the angle between galaxy pairs so if it's further on the Left that angle between galaxy pairs of small you're looking at galaxies that are really close together.

Justin Myles: On the right you're looking at galaxies that are really far apart. Justin Myles: And on the y axis the vertical axis of the top panel, it says how likely, are you to find a pair of galaxies separated by distance.

Justin Myles: So don't worry about the numbers but higher means more likely lower it means less likely.

Justin Myles: And the data what we measured by with 100 billion galaxies the black points the black circles, with little tick marks above and below them so that's what we measured we measured.

Justin Myles: exactly that galaxy clustering what's really interesting when I want to point out about this is that this relates directly to to things like dark matter and dark energy.

Justin Myles: This is a quantitative way of showing it, however, so there's something there a couple of the elements of the plot, and we as scientists, we always look at every element of plot.

Justin Myles: So in addition to the points there's also a black line with that black line is telling you is what is our best fit theory.

Justin Myles: To those data, so we came up with a theory for the universe, which has a certain amount of dark matter and certain kind of and amount of dark energy and that theory tells you exactly how much clustering you should see.

Justin Myles: And you'll see that that theory or model matches the data quite well. Justin Myles: So the black the black curve matches with the points now what we've added to this plot specifically for you as an audience is what happens if we just added way more dark matter.

Justin Myles: And that's what's shown in the oranges curve, so if you add if you put 20% more dark matter and that changes.

Justin Myles: How what the galaxy clustering measure is so you can see here and it's very subtle effect when you look at it like this, but this is, this is what the data are.

Justin Myles: Adding 20% more matter to the universe changes this measurement so now, you can see, yes, the measurement we've done it tells you how much dark matter, there is the universe, the other, the other curve, the purple is, if you had 20% less dark matter compared to our best estimate.

Justin Myles: The bottom panel is showing the difference between the curves to make it a little bit more obvious.

Justin Myles: And since we're doing this exercise is one more feature in this plot and that's there's a Gray bar like a Gray rectangle on the left hand side.

Justin Myles: that's because, as I said earlier in the talk this story of telling you this tug of war, it determines how the universe looks on large scales of distance and time.

Justin Myles: Once you get into small scales so galaxy they're separated by small angles, other things start to matter things like exploding stars and exotic astrophysical things that can dump energy and blow like extreme winds into space and that'll affect that will affect.

Justin Myles: The clustering of galaxies so all those small angles. Justin Myles: That are represented in the Gray region that's where we're saying you know all this other complicated astrophysics.

Justin Myles: is just dealing it's just interfering too much with our ability we can't simulate it it's just interfering too much so we're going to throw out those data.

Justin Myles: So, the reason I point that out, is to give you the sense that we have to be extremely careful about what data we use, you can see here a huge amount of the data we're actually throwing away because we can't be.

Justin Myles: We can't be perfectly sure that we can simulate all those complicated astrophysical effects well enough.

Justin Myles: And that brings us to our our end here, this is the big result. Justin Myles: So this plot is showing on the horizontal axis what fraction of energy in the universe is matter so remember I said earlier, was about 25 or 30%.

Justin Myles: When you add up the ordinary matter in the dark matter that's what's shown on the X axis, you can see the number ranges from on the left hand side 25% on the right hand side over 42%.

Justin Myles: And the y axis is how clumpy is the matter of the universe, we don't have to talk about quantitatively what how we make a number for that question, but just trust that we make a number for that question.

Justin Myles: And as i've said scientists can never tell you exactly or experiments can never tell you exactly what the true, the true value is.

Justin Myles: We can only tell you where we believe it is on with some uncertainty, so that I have a quote from the catcher and the rye holden caulfield said, people always think something's all true and that's of course never the case.

Justin Myles: So we think from the dark energy survey that that the true value of these two numbers together lies inside the Gray, the black ish grayish to region.

Justin Myles: We think the best estimate is really sort of toward the Center there that's, we think that our best guesses. Justin Myles: But what all we can really say is that we are 68% sure that the truth is within the inner dark circle and we're 95% sure that the truth is when the the outer grayish region.

Justin Myles: So that's that's how we communicate our understanding of the what the true value must be given our data it's probabilistic.

Justin Myles: And what's really interesting here is to compare this, as I said, we do with observations of the oldest light in the universe, which is an agreed.

Justin Myles: So that's similarly what their experiment of the oldest light in the university cosmic microwave background gives you.

Justin Myles: And these results are not inconsistent, because the truth is in these large blobs and there was an overlap between those large blobs.

Justin Myles: But it's interesting that they don't completely overlap in a sense, it's interesting that the late universe says there should be, it should the universe, be a little bit less clumpy is less less clumpy.

Justin Myles: This could just be a statistical fluke but it turns out, you can do many other measurements. Justin Myles: similar to what we've done and they're all just show that the late universe experiments are just a little bit lower.

Justin Myles: And that doesn't mean they're necessarily disagree, but it's a bit suspicious suspicious and that it suggests, maybe we aren't understanding.

Justin Myles: Everything that we're measuring perfectly well, or maybe our model for the universe, the story we tell about how the universe is developed is missing, something.

Justin Myles: The fact that it seems to be showing some cracks under stress is something that's very interesting to us because it's been confirmed by multiple experiments.

Justin Myles: And this, of course, relates to dark energy, because the clumpiness, as I said, is in part two, due to.

Justin Myles: The nature of dark energy, so this is the state of the art I wish I had an answer to give you, but we don't have that quite yet we're hard at work, trying to better understand what's going on here.

Justin Myles: So to end our summary is then that are cosmological model is at once very successful and demanding of increased scrutiny we're hard at work, to work out the remaining mysteries.

Justin Myles: With that i'm excited to start the question answer session with Dr. Ami Choi and Dr. Spencer Everett, two other collaborators in the dark energy survey, who are experts in how we do these measurements, looking forward to your questions, thank you.

michael peskin: Okay well justin Thank you very much, very beautiful talk these slides are gorgeous.

michael peskin: We will now open the discussion for questions I remind you again if you many people have written questions into the question and answer box, but if you have more questions, please just type them in we'll see how many we have time for and maybe you should go ahead and introduce the panelists.

Justin Myles: Great yeah so everyone should be able to see Ami Choi, Dr. Ami Choi and Dr. Spencer Everett soon they're both.

Justin Myles: they're both scientists working in the dark energy survey at California Institute of technology, Caltech.

Spencer Everett : hello, can you hear us. yeah we can hear you.

michael peskin: Can we change it to the gallery view so we can see everybody.

michael peskin: Well, while we're trying to do that. michael peskin: Let me shoot you folks some questions first some more practical ones Martha was very interested in the picture of you justin at the beginning, sitting at a desk with a lot of computer terminals in front of you.

michael peskin: um that was taken at Stanford. michael peskin: And the telescope was in Chile.

michael peskin: So. michael peskin: How does that work. Justin Myles: yeah in this case the telescope was in Arizona.

Justin Myles: And yes, this picture is taken at Stanford. Excuse me.

Justin Myles: We can we can downlink the data over the Internet, essentially, so this was done over zoom we also that we have a special observing room, which has.

Justin Myles: Some things that help us for this kind of thing, where we, we have an extra power supplies if the power went out we'd still have power in our room for our computers.

Justin Myles: and have a more reliable Internet connection but yes we're interacting with people who are on the mountain itself we're operating the telescope.

Justin Myles: And the scientists tend to operate the instruments, the cameras that are collecting the data so here this interface with these screens were operating the instruments, the camera.

Justin Myles: The fiber optic cables that are collecting light and the people on the mountain are operating the operating the telescope itself sometimes we're lucky enough to be able to go to the mountains over the past year that's been more difficult, of course.

michael peskin: The schedule for which way the telescope is going to deploy, it has to be worked out well in advance?

Justin Myles: Yes, so it should be, but, of course, things always change, so we do have to think on our feet all the time to adjust to the fact that.

Justin Myles: If clouds are covering the sky and you miss you know you delays you, what do you then do with your schedule that's an it's not a perfectly solvable problem you have to.

Justin Myles: make concessions depending on things that you can't control, like the weather and instruments not working properly so you're always thinking on your feet, which can get more challenging as as the night goes on.

Spencer Everett : When they all add there is that. Spencer Everett : is just insane it's incredibly important to figure this out quickly because telescope time is very expensive, so you need to have the sorted out and be able to adapt to the situation.

Spencer Everett : And one of the ways we handle this in the dark energy survey is actually a lot of people spent.

Spencer Everett : Many years working out algorithms that would take in all of this live data as we were going so we start the night saying, I want to look in this part of the sky because we're missing data there.

Spencer Everett : And it's going to be high up in the sky with with less atmosphere, but then there's a cloud there and it will automatically adjusted situation beside the point somewhere else with conditions that are better.

Spencer Everett : Now, and sometimes when you're observing, you have the luxury of something that Nice, and you have to do more of this mental processing on your own, but we also spent a lot of time trying to automate these processes for you.

michael peskin: Okay um there's also a question about the camera, you said you need special chips for the camera which are thick what's the process for that

michael peskin: Are these off the shelf, things are you have to actually order these chips to be manufactured.

Justin Myles: yeah in the case for our our kinds of experiments, these are special ordered specially designed for our experiments.

Justin Myles: i'm not an expert on this, my understanding is that these these chips, which can be made of silicon or are grown as crystals.

Justin Myles: And we actually we have to then understand, because these are special made, we have to understand very well how they respond to light so, for example.

Justin Myles: One of the things that affected the dark energy survey camera is because these crystals are grown over time and.

Justin Myles: The humidity conditions in the room, in which they're grown can change there can be slight aberrations slight changes in the the silicon itself and that'll affect how sensitive it is to light.

Justin Myles: These are things that are really in many ways, inevitable, but we just have to understand them really well to essentially correct for them.

Justin Myles: I don't know if the other panelists have thoughts too. Ami Choi: I think you answered that really well I, I know that they were made specifically at Lawrence Berkeley national lab so they were made by scientists, although some detectors made for telescopes are made by commercial companies as well.

Spencer Everett : And in fact one of the reasons DES got so much observing time for survey is that we donated the camera to the telescope when we were done.

Spencer Everett : And so the way we kind of bought our time was by developing very nice state of the art camera and getting to use half the time with it, and leaving them to keep the rest.

michael peskin: it's maybe it's worth noting that SLAC is now mounting a I believe two giga pixel camera a much larger camera one another telescope, which is in Chile.

michael peskin: which will take its first light next year in 2022 so that's called the large synoptic survey telescope or actually now it's named after one of these covers of dark matter Vera rubin observatory and that's The next step.

michael peskin: um. michael peskin: Edward had a very basic question so, how does the universe get a web of dark matter.

michael peskin: dark he says dark matter should just move and clump up into one big universe lump because nothing affects dark matter, except gravity so, how does the dark matter a get spread out all over the place, and b, some form then into these lines and voids that you should have in the pictures.

Justin Myles: yeah so I could start to answer that and i'm sure the other panelists will have things helpful to add.

Justin Myles: So dark matters primarily affected right by gravity, which we know affects it but keep in mind that the expansion of space is something it's in in some sense gravitational effect as well, so dark matter does not.

Justin Myles: It does not overcome that right it's it is subject to that as well, so it's something to that effect.

Justin Myles: And also, we we at this point, know that dark matter interacts with other stuff only very weakly we actually have not ruled out that it interacts with other stuff.

Justin Myles: at all and, in fact, all the experiments were running here on earth really rely on the hope that it does interact with other stuff.

Spencer Everett : yeah so that's a really great question and I think that intuition is basically right, if you look at a patch in the universe there's a bunch of dark matter, what does it do it collapses in the blobs of dark matter that's exactly what happens.

Spencer Everett : But there is no, you know Center of the universe that you know there's it's not just a little ball.

Spencer Everett : it's collapsing into those balls all over the place from the early universe, for there happens to be just a little bit more mass from just from randomness and.

Spencer Everett : Eventually the scale gets big enough that the gravitational attraction between those different fronts as much weaker than dark energy as justin was alluding to.

Spencer Everett : So your intuition is right it's just happening all over the universe, and then mattering between these things starts to fill the connections, which creates that structure.

michael peskin: And the voids are formed by the dark matter moving out of one region toward other regions that attracted.

michael peskin: So, eventually, you get this kind of pattern so.

michael peskin: Okay, Gerry has the following question, we know that in the local universe there's something called the great attractor where there's actually matter out there that's pulling local galaxies I believe toward us.

michael peskin: And he wonders whether this could be the explanation of the overall stretching of the universe, as an alternative to dark energy is it possible that there's some matter if they're outside of our view that actually through its gravity is causing the universe to expand.

Justin Myles: interesting question to start to Spencer, Ami, do you have thoughts off immediately to answer that question.

Ami Choi: Well, I think we're getting a lot of data from these big surveys and telescopes at many different like looking back in the time.

Ami Choi: and looking at larger and larger volumes of the universe so.

Ami Choi: I my intuition here is that it would be pretty hard. Ami Choi: To have something like that really explain all of the observations that we see and I guess that people probably have also run simulations of this to see you know how would that impact observations that we can make.

Ami Choi: You know, like the ones that doesn't work was speaking about.

Ami Choi: But I think that we have, we have a very wide range of observations, going from galaxies that are local to us and, of course, there we can't really see that far, so there might be something kind of hidden from view, but we also have observations.

Ami Choi: For very distant locations in the in the universe, or rather, you know, looking back at the university early times and I think it might be hard to to for that to be the explanation for the dark energy.

Spencer Everett : And in addition so i'm guessing this is kind of where the questions from we we do know.

Spencer Everett : kind of great attractor like thing in the semi locally universe it's a big blob of stuff that has a big gravitational pull that makes us maybe not in the most uniform area.

Spencer Everett : mattered and see universe, but at least, from what I had read the effect of that even if you're extremely generous and how strong that effect could be was a fraction of what you need to explain the dark energy measurements.

Spencer Everett : So even extremely anomalous things like this, have an insufficient to spend our energy so, then you quickly have to design a very strange system to explain.

Spencer Everett : Our effects versus something like dark energy, which is a single number in a theory that already can allow it so it's far simpler to assume that something like dark energy exists, it requires much less strange oddities and construction.

michael peskin: Yes, stormy has another question which is relevant to this one she'd like to know um you describe the early universe, the universe of the cosmic microwave background is being very smooth.

michael peskin: So how do we know how smooth it is how do we measure that and also if it's very smooth where did the little unevenness that you talked about confirm.

michael peskin: So maybe you folks can address both of those questions, how do we know it was so smooth back then, when the cosmic microwave background was emitted and where did the little bumps on it come from.

Justin Myles: yeah I mean this is really good great question, and while i'm not an expert on this, I can say that, so the smoothness.

Justin Myles: it's hard to hard to tell from the image I showed, because the image I showed was in many ways, designed to illustrate what clumpiness was there.

Justin Myles: But it was the smoothness is evident when you just. Justin Myles: Change the scale of how what clumps you're looking for, so it was millions of degrees was the units of the color changes so if we had looked at thousands of degrees.

Justin Myles: or hundreds of degrees 1% of a degree, it would look much more smooth and we describe it as smooth the original observations, of course, done and I think 1965 it was just a completely smooth map and the big question is, what is this as far as what is the origin of this.

Justin Myles: It the root of the idea is in the randomness of quantum mechanics so in the early universe so quantum mechanics is really inherently probabilistic theory.

Justin Myles: events are determined inherently probabilistically and. Justin Myles: that's happening in the early universe, the distance scale of those quantum mechanical this quantum mechanical rules.

Justin Myles: is more relevant right so now the distance scale, now.

Justin Myles: That distance scales very small when the universe itself is smaller that distance scale has a different impact, so the inherent randomness of the laws of physics and, in particular.

Justin Myles: quantum theory is going to inevitably lead to some differences and perhaps other panelists have better answers as well.

Spencer Everett : No, I think that's a great answer on both fronts and just for added context you showed the great.

Spencer Everett : picture of the CMB and these would look like huge fluctuations that, as you said, been scared that just to give people an idea.

Spencer Everett : I mean it's it looks like this, Big Mountain side, but if you actually looked at it like in person, it would be like the peaks and valleys are one part, and like 10,000 or 100,000 it's very, very, very tiny changes.

Spencer Everett : But if you have a very sensitive instrument and can capture those I mean we get so much of our cosmology just from this tiny fluctuations of the fact that which is small.

michael peskin: um let me back up and ask another kind of more instrumental or practical question.

michael peskin: You talked a lot about the distortions that comes from the sky, the fact that we're here on earth and light is coming through us to us through the atmosphere.

michael peskin: Of course that's not true for telescopes in space and so rob would like to know how you compare your telescope to that of the hubble space telescope.

michael peskin: I guess it's much bigger, could you give us an idea of that, and is it possible for hubble or some other future telescope that we put in space to do this kind of survey.

Justin Myles: yeah so the big difference is that it's much bigger it's hard to put large things in space.

Justin Myles: Now of course we're always improving so a future space telescopes be bigger than past space telescopes but that, as a general rule that is a fair thing to that's the general rule it's hard to put big stuff in space.

Ami Choi: yeah so hubble I think is like a 2.22 point something diameter mirror and in meters, and so the the telescope that we're using for the.

Ami Choi: results that justin showed that's like a four meter diameter in a mirror, but the main difference is that the camera is much, much bigger and heavier.

Ami Choi: And so the I think the largest cameras that are flying on the the hubble space telescope are really a tiny fraction of the like what you can get in your field of view so how much of the sky at once that you can see.

Ami Choi: I don't remember the exact numbers here, but a very small.

Ami Choi: fraction. Ami Choi: And then justin mentioned, there will be future space telescopes that will go up so one of them is called the Roman space telescope and that will hopefully launch.

Ami Choi: Later this decade, so in the mid 2020s is when it's supposed to lunch and that one as a similar size mirror as hubble, but it has 100 times the field of view, so the camera is much, much bigger so that that experiment will also be used to measure.

Ami Choi: Like weak lensing and galaxy clustering the kinds of observations that justin was describing.

Spencer Everett : And since they got the answer the question. Spencer Everett : First, like it's a. Spencer Everett : backup with some googling so yeah so the the main hubble cameras, you know it's a less than 30 times the size of the one in DES and it's because we're on the ground as they said, you can be much bigger, and so we have over twice the collection area twice the bucket size for the light.

Spencer Everett : And that's all great we can build these giant ones on the ground where of course the huge drawback of our ground based telescopes is, we have to look through the atmosphere.

Spencer Everett : And all the twinkling stars, the twinkling is a terrible thing from the astronomer it's all the light getting distorted and so.

Spencer Everett : it's always this trade off between really big telescopes on the grounds that have worse resolution of what's on the sky versus these kind of smaller instruments that can zone in and make the pretty pictures like Hubble but can't cover the whole sky.

michael peskin: So Eric has the following question for you. michael peskin: justin you talked a lot about trying to infer things from the shapes of galaxies but how do you know what the shape of a faraway galaxy should be.

michael peskin: So it's distorted, but you don't know what the original shape was why isn't that far away galaxy to shape sort of elliptically instead of spherically or disc like instead of.

michael peskin: Round um, how do we know if it's being stretched by gravitational lensing or whether it was just that way in the first place.

Justin Myles: yeah truly excellent question um I the same question is the first year graduate student, Ami is one of the world experts on this so maybe I'll let Ami answer.

Ami Choi: Sure yeah yeah, it is a great question, and so we we don't know for a given galaxy what its original shape look like.

Ami Choi: Because galaxies we think it can come in many different shapes and sizes and so what we have to do here for a weak gravitational lensing.

Ami Choi: Is do a statistical analysis, so what we're specifically trying to measure is the coherent distortions of galaxies so really for any any given galaxy like any single galaxy.

Ami Choi: The gravitational lensing effect that is applied to it is really typically less than a percent of the actual ellipticity of that galaxy so for that one galaxy we can't really tell how much it was lensed but by doing averages over.

Ami Choi: So, as the cases for DES over 100 million galaxies, then you can measure, a statistical distortion, which is like coherent, so we specifically look at, for example, pairs of galaxies and we tried to measure.

Ami Choi: Whether those two galaxies seem to have a coherent distortion so there's something that slightly changes their orientation to be slightly like in a particular way, as opposed to just completely random.

Spencer Everett : that's a great question Spencer Everett : it's exactly what we worry about.

michael peskin: AC has picked up, I think you didn't mention it in this talk on the the current problem of the hubble constant, which is the rate of expansion of the universe.

michael peskin: So there's been some news that there's a discrepancy between the hubble constant measured by plunk and novel constant measured more locally by Type one a supernova.

michael peskin: And he'd like to know or she'd like to know, has this been resolved, and what are the implications if there actually is a discrepancy, and maybe I should also add could that be related to the possible small discrepancy that you showed on your last slide.

Justin Myles: yeah really great question happy to start with the answer for that, so this problem, called the hubble tension relates to measurements of how fast the universe is expanding locally.

Justin Myles: compared to what it what it should be from early observations of the observations of the early universe, if you roll the clock forward to today and there's a discrepancy and.

Justin Myles: If you measure if you measure and actually that expansion rate is faster and this discrepancy is more significant it's more intention with early universe, and the measurements we're showing today, however.

Justin Myles: It is important to consider them both it's important consider them both at the same time.

Justin Myles: Because they they appear to be they appear to be they could be telling a story because less clustering from late.

Justin Myles: universe measurements also more faster expansion from late universe measurements, they could be they could be telling us something about the nature of dark energy, but it is also possible that.

Justin Myles: They are the result of these measurements being very hard to do and that's not counting for everything so to answer the question no it's not at all resolved, it is one of the burning questions that really I think motivates a lot of us and.

Justin Myles: That That problem is actually statistically more significant than our problem, and we hope we are searching for answers.

michael peskin: Okay, I think we have time for just a couple more questions, one of them, this may cover some things you've discussed before but it's a very important question.

michael peskin: Um Christian would like to know, I understand that dark matter interacts with regular matter through gravity.

michael peskin: But does dark matter also interact with other forces like electromagnetism strong and weak force and, similarly, do we know what it's made of.

michael peskin: And let me just add to Christian's question are we getting insight into that from the dark energy survey were these things are too weak to measure in the dark energy survey.

Justin Myles: yeah so a top level just to start the top level is that.

Justin Myles: We have many experiments which are attempts to make direct measurements of dark matter and those rely on it's interacting, for example with electromagnetism.

Justin Myles: If it interacts with electromagnetism we know it only does so very little that's what we know so far, but it still could interact with electromagnetism in some way and that's what many ground based experiments to detect what it is detect to the particle the principle there rely on.

Justin Myles: Now, about the nature of dark matter, there are other forms, there are other experiments within the dark energy survey which get closer to that so, for example, looking at particular individual kinds of dwarf galaxies can shed light on the nature of dark matter.

Justin Myles: Because, looking at the dynamics of the system itself can tell you more about this, the strengths of these kinds of interactions i'm not an expert on that so maybe other panelists have information on that.

Spencer Everett : Something i'll just add on as another example of a place, you can try to understand. Spencer Everett : dark matter energy survey isn't galaxy clusters these huge most massive gravitationally bound things that we know in the universe.

Spencer Everett : So they're really great studies that look at these extreme environments. Spencer Everett : And so, as a previous question asked you know why doesn't bark managers all come together and blob up that it's basically what it does, but if dark matter.

Spencer Everett : interacts with itself, the way it will block together and the Center is very different than if it doesn't interact and it will just screen right through itself.

Spencer Everett : And so there'll be more diffuse if it doesn't try to interact with itself, like all of our particles do, but if it does, it becomes more cuspy.

Spencer Everett : And so, if you can make it extremely precise measurements. Spencer Everett : In cluster quarters with are really nice camera be really careful about the blending all the light.