now for the main event our speaker tonight is David Miller David is a

graduate student at Stanford a graduate and undergraduate student at the

University of Chicago where he worked on a small particle physics experiment he

came to Stanford to work on a giant particle physics experiment as you'll see a member he is not a member of a

worldwide collaboration at an accelerator based in Geneva Switzerland 3,000 physicists from all over the world

it is very daunting for a graduate student to make an impression in such a

large group to do that you have to be incredibly brilliant work 24 hours a day

and stick your nose in everything and that's what David is known for we

managed to pry him away from his computer to come and give you a talk about what is going on now at the LHC so

without further ado let's smash some protons thank you very much David

all right so I hope everybody can hear me I'm often actually told to be even

more quiet than usual so let me know if you can't hear anything it's it's really an honor and a pleasure to be here

tonight I'm gonna try to describe to you and lead you through a little bit of a story of what we do with the Large

Hadron Collider as as Michael introduced this is an extremely large worldwide

collaboration but one in which slack plays an integral role we we have a

large group of physicists and scientists that are both there and here are working together with people from all over the

world to understand what's going on in this really unique accelerator this really unique machine so without without

further ado let's actually get started so I'd like to put this whole picture in

a little bit of a context by showing you a short video where we take you from the

outer reaches of the cosmos down into Geneva Switzerland where the experiments actually taking place so you're all

familiar with the milky way where we actually sit and in fact the accelerator is located just outside of downtown

Geneva so as you zoom into Europe and Switzerland and now into the city of

Geneva itself you can see the outline of the accelerator sitting on the surface

just outside of downtown which is over here but in fact the accelerator itself

sits almost 300 feet underground so taking you there now this machine is

very unique it's 17 miles around it's located it's it's located 300 feet

underground and each of these experimental halls is actually the site of the proton-proton collisions that are

helping to that are hopefully going to help us understand the basic fabric of the universe and so these are the

locations that we perform our experiments on a daily basis millions of proton collisions occur every second and

in fact as we dip down into the accelerator itself you can see the magnets which bend these around this

huge arc and actually eventually collide at the at the location of the various

experiments which then take snapshots of what happens in these enormous lis energetic collisions millions of times a

second so I'd actually like to just briefly show you one more short video

where we where I point out the the actual collisions themselves so the

protons start in a booster system on the edge of the accelerator and then there

there's shoved into a small ring where they get up to speed nearly the speed of light in fact only a fraction of a

percent lower than than light itself then they're flung around the Large Hadron Collider where they meet in

various points around the ring but like I mentioned one in one experiment in particular the Atlas experiment takes

these snapshots of the collision every time they occur and so this is this is the essence of what we're trying

to do is really to take a picture of what's occurring in the in the collision of these two protons and hopefully try

to understand exactly what makes up the fabric of nature itself so this is this is all gonna go into much more detail

but I wanted you to get a context for the for the situation that we're actually dealing with so here again is

the ring of the Large Hadron Collider 17 miles around and to give you a feeling

for extra the actual size you have here the Geneva Airport which is just a tiny section on one side of the Ring you can

see in the background the Alps of this both Switzerland and France in fact the

border of Switzerland and France runs basically right through the ring itself and in fact just to prove to you that

that that this was in fact safe my apartment was actually situated almost

right next to one of the collision points but most importantly it was far away from the competition which is the

experiment that I don't work on on the other side of the Ring called CMS now I'm not going to talk much about that I

will tell you however a lot about our experiment and the one on which a lot of slack scientists participate in many

different ways and that's called Atlas so that actually sits on the side slightly closer to down

Geneva and much closer to my apartment and like Michael said I didn't have much time to sleep so that was very useful

all right so appleís is really a global endeavor more than 37 countries from

around the world as was introduced thousands of scientists from all over

the world you can see actually here a map which is colored representing the various countries that participate in

the in the experiment and in fact as you can see in alphabetical order as usual

the United States is is really a crucial player and in fact slack is just one of many laboratories and universities

around the country which contributes to the experiment and to to CERN in general

and in particular the CERN relay race which you can see a small fraction of

the of the slack team here was actually this is just this year's this year's race we didn't quite beat the protons

around the ring but we tried we didn't come in last that's for sure you can actually see a picture down in the

bottom right this is one of the buildings that houses a lot of the graduate students night and day there's

a lock and key on the on the outside door we're not usually let out but there are hundreds there are hundreds of

people which obviously only represent a small fraction of the entire collaboration okay

so I've told you a little bit about what what who the people are which going to this and where they're located but I'd

like to step back a little bit and tell you I think at least in my opinion why we're doing some of this so I just want

to give you an a sense first of how big the experiment is so you can see here

this is a very famous photo of the construction of Atlas this is during right before we move this central piece

into place I'll actually describe what that piece is in a little while and I'd like to point out that this gentleman

here wearing a hard hat we're big on safety is is dwarfed in comparison to

the experiment as a whole and and as I mentioned they do put us hard to work so

this is this is me crawling around in between the magnet system and one of these one of these electronic stores

here screwing things into place and it looks like we got all the cables in the

right but like I said I'd like to put this in in a little bit more global of a

perspective so humankind has really always sought to understand the world in

which we live we've always asked questions and we haven't always performed experiments and

one thing that we've learned is that we often need these new ways of looking at the world in order to really begin to

see it for its true self I mean one way of thinking about that is that new perspectives are really often the result

of new technology when we are able to gaze out at the world with a new device

with a new set of glasses we often see things that either we couldn't see well

enough beforehand or that we didn't expect altogether and that's actually I think one of the driving principles

behind the science which is going on both it's slack and it's CERN with these large accelerators because it gives us a

tool to try to understand the world by looking at its most minut components so

to put it another way oftentimes science is really only as good as its tools I mean one one

wonderful example is is Aristotle he was really the father of modern science and in multiple fields in fact as an

undergraduate I I was confused for a little while and studied philosophy but quickly got back on track and and you

know from physics to zoology cosmology just to name a few Aristotle really played a key role but

honestly his lack of experimental data and methods like thermometers for example often led him to draw incorrect

conclusions he famously said that women are fundamentally different than men and

and have a lower body temperature and that was one of the ways in which he differentiated the species and in in

addition you might you might know that he was also a huge proponent of the idea that the earth is the center of the

universe so a lot of the the conclusions that he drew although informative for

science and humankind as a whole were were lacking in in his ability to test

them against the real world phenomena and that's something that we try to do in experimental physics is try to use

the the knowledge that we have and continually beat it against the wall and ask whether it really has

everything that we expect it to in order to move further so a wonderful example

of this is Galileo and the telescope I'm sure people are very familiar with this the the sixth sorry the 400th

anniversary of the telescope was was just recently and very famously he was

able to look out into the Stars finally with this new device and one of the first things that he did was to look at

the moon and instead of seeing the the perfect spheroidal heavenly body that

was purported to be there he and saw he instead saw very rough very cratered

surface something that he thought honestly looked a lot like Earth and there was no reason to think that this

object out in the cosmos was any different than the object on which he was standing and this was the beginning

of a huge revolution obviously it took until Copernicus for this to really take hold but it revolutionized along with

Newton later on who made more detailed measurements revolutionized our perspective of the cosmos and really

allowed us to sort of step back and see beyond ourselves so we've taken this

idea to a whole new level as just an example you have the Hubble telescope so this is the same principle but a new

technology a new application of the Galilean of the Newtonian telescope so

it's built on age-old principles but it allows us for example by looking deep deep into the universe to see

essentially backwards in time so one thing that the Hubble telescope has allowed us and has told us about

ourselves is that there are things early in the universe which are different than

the universe today and in fact you'll see that this comes back when I describe what the science that we're doing at the

Large Hadron Collider in terms of describing the universe in which we live in and actually where it has come from

and perhaps to some extent where it's going all right so this is exactly what

I was trying to say the Large Hadron Collider is essentially another type of telescope but instead of allowing us to

see very far away it allows us to see the smallest constituents of the universe that there are and it does so

by colliding protons and really these these constituents are sort of the

building blocks of the universe that have been around since the Big Bang itself and so the endeavor that we are

that we are embarking upon is to try to understand those components in order to understand the universe in which we live

so the I've been talking a lot about this fabric of the universe about constituents about and sort of inferring

the idea of particles so what do I really mean well we understand over the last 50 years through experimental and

huge advances in theoretical physics that there are a set of fundamental building blocks that comprise the

universe a lot of you are are I'm sure familiar with some of these ideas inside

the atom that make up essentially everything that we know the tables and chairs in this room we have nuclei and

inside there we have the proton and then inside the proton you actually have a somewhat more fundamental object called

the quark and to our knowledge today this is the smallest component of the sort of physical universe that makes up

the things that we know protons and neutrons your your bodies the the air that we breathe etc but so far the tools

that we have have not allowed us to go any further is there something else behind quarks for example this is

actually very well represented in this picture where I mean it's it's very clear that we go for both

by understanding the constituents of nature we hope to understand ourselves and so one of the primary tasks that

we're trying to do at the LHC is to understand the universe by looking at

what it's composed of and and the pieces that are there and in turn in some cases

the pieces that might be missing so what we know so far and is that we have we

have a set of these particles and so we have something that we call the standard model of particle physics and so that's

basically all it attempts to do is to break down the universe into just a

simple table you have a table of blocks which you can build the universe with and we can put them together in various

ways we can make protons we can make other particles called maisons we can make all kinds of things that we know

from the world around us inside the the proton for example like I mentioned are

quarks but in fact there's six types of these corks alright I can deal with six that's

a that's a fairly good number but then in addition to these corks there's the electron this is what enables your iPod

to play your music and the the lights in this room to shine there are brothers

and sisters of the electron called the muon and the Tau together these are all called leptons along with their cousins

the neutrino now you may have even heard about the neutrino it's a very very lightweight particle which essentially

passes through much of anything but what's what's important is that there are these various classes of particles

which we know exist experiments here at SLAC at other laboratories around the United States have proven the existence

of these particles beyond the shadow of a doubt but the question really is is this the entire picture that we can

construct of the universe in addition you have the force carrying particles a Z boson

so actually keep keep that than what that one in mind that's something that I'll talk about in the results that we have from the Large Hadron Collider the

W boson these are very similar they're related to the weak force in physics you

have a photon which you're all very familiar with you wouldn't be able to see me without it and and particle like

the the gluon or perhaps the the graviton which which might be the the

force carrier for for gravity but then underlying the idea of these massive

particles is something called the Higgs boson so this is something that you also might have heard about it's related to

the idea of mass itself and so I I'd just like to prime a question to you why

why do the particles of light shining to us from from the ceiling not have any

mass we know that we can test it they go to the speed of light while other particles actually do have mass what's

the difference we don't we have a supposition as to what the fundamental difference between those particles is

but we need to test that we're scientists we need to ask the questions that will prove that this is the the

right way to look at the world so what is the Higgs boson well you could imagine a crowded a crowded room a

cocktail party for example I'd just like to to surmise that the big

particles are like are like are like the crowd at a very popular cocktail party

now imagine a very interesting guest walks in the room professor Einstein for example as he tries to walk across the

room people want to talk to him people want to ask him questions it becomes more difficult for him to move across

the room quickly he has to slow down he he gains some inertia if you can think of it that way and so you know in a

sense these Higgs particles this Higgs field which is which is permeating this cocktail party is slowing down is giving

this this professor this particle if you will mass so the answer to the question is

that massive particles are kind of like popular party guests as they as they move through this see of the the Higgs

boson field of the the Higgs particles themselves this it endow 'zed mass

through its interaction with these particles so this is an idea and we're trying to test this that's that's what

spare experimental science is all about and so the Higgs boson will come back in a little bit now we also know from

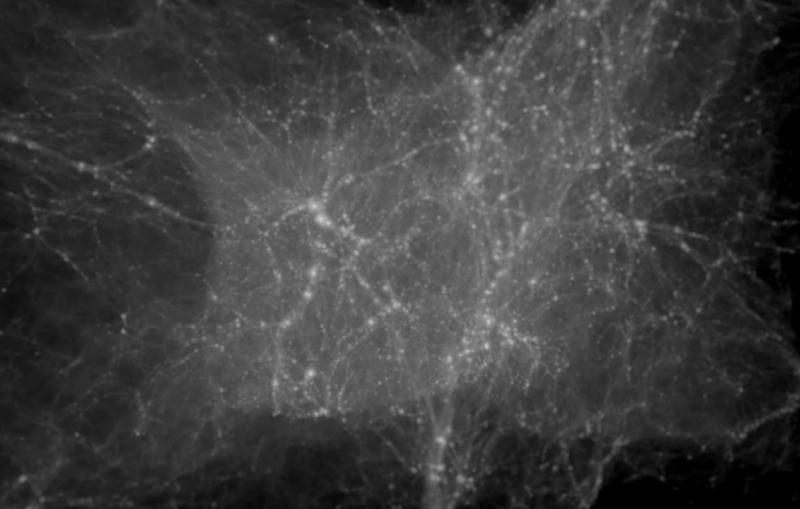

looking out into the stars and and looking at various objects in the in the galaxies and in the cosmos that there

are pieces missing from this puzzle this table that I showed you is is not complete it's not wrong but it doesn't

tell you the whole story this pie chart is actually a talk in and of itself but

I would like to point out that that the sliver here this point four percent of

the universe is really the entirety of the stars and planets and people that we

can see when we look out into this guy's there's an entire ninety-nine percent except for gas so there's an entire 96

percent of the universe which were not sure what it is in fact this sliver here that I've

outlined this 23 percent is a very mysterious form of matter called dark matter which is really the boring

physicists way of saying I don't know what the heck is going on so what you

have in this in this bottom right picture is something called the bullet cluster in fact this is this is an experimental observation which slackened

and the Kavli Institute here was crucial in understanding I'm to try to explain it to you very quickly

but hopefully understandably but it this is this is an extremely deep subject in

and of itself in red here this is false color are actually the gas the hot gas

imaged from from essentially telescopes looking out into the sky of two galaxies

that have collided and moved through each other so this happens all the time this is this is nothing to be cried over

galaxies galaxies collide it's a cosmic car accident if you will but in fact

because stars and gases are relatively fluid they tend to sort of pass through

each other with a little bit of friction and so that's what you see in the red you see that the gases and the stars are

sort of left behind as they pass through each other you see almost like a mock jet passing through the the sky

creates a sonic boom and you see the sort of shockwave out in front you can see that almost clearly on the right

side here but there's another component there's a whole other piece to these galaxies which you can't see with just a

simple telescope you actually need to use a whole other set of tools to look at this and when you do so you see that

there's a whole part of the galaxy in fact more mass than is contained as I showed you before as I showed you in the

pie chart more mass than is contained in the gases themselves has just passed right through it's not affected there's

no shock front it's out in front it's winning the race if you will and so this

is exactly the stuff that we call Dark Matter we don't know what it is but we know that it's there you can see it

through its interaction via gravity all right so we put this together we have

questions we want answers could there be more to the universe than we see could

there be more than just our four dimensions of space and time we live in three dimensions in space and one of

time could there be another dimension of space could could gravity be leaking away and that's why we think we see

these weird gravitational effects could there be an entire mirror universe of undiscovered particles here you have a

cork here you maybe you have an electron here you maybe have a Tau neutrino could

there be in another mirror an entirely other mirror universe that has a sort of analogous particle for every particle in

the table I showed you we don't know if they're massive enough they could have sort of hidden they could be sort of

hidden in the in the fabric of the universe without having been detected in the experiments that we've conducted so

far so we have questions we want answers and that's really where the the accelerator physics and the Large Hadron

Collider come into play so how does an accelerator show us what these particles are I think I think that's the natural

question to ask at this point well Einstein gave us a wonderful tool and

that's e equals MC squared is a very simple equation but it's got a very powerful meaning and it means that on

the one hand you can take energy that's the e and turn it into if you've got the right conditions matter on the other

side that is you can sort of trade the energy of motion that it the energy that you put into a particle by accelerating

it for the mass energy of other particles all right so what is that what

does that mean well that means that when you collide two protons remember I showed you that we've accelerated them through these boosters we've got them

going nearly the speed of light and then suddenly we bang we smack them into each other what can happen is that the energy

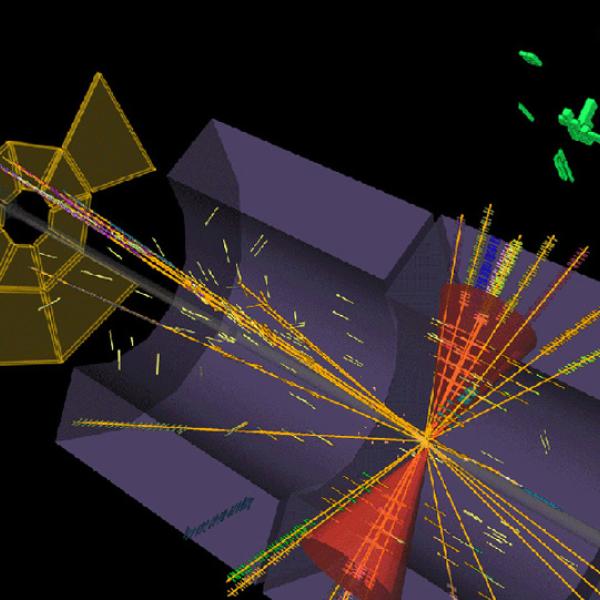

that you've put in can turn into new particles coming out so here is actually a set of particles which I'm going to

describe in detail later called the top quark so in fact this is a very interesting particle because it's

extremely heavy whereas the proton is is just a very light particle in terms of

the table that I showed you before the top quark is is as heavy as nearly 200

of these protons and it's just a single particle why why is it so massive it's it's a very interesting question and

we're already beginning to study these things in great detail so okay how do we

do this how do we exchange this mass energy well you might have guessed it it's the title of the talk we smash

protons together we get protons or lead ions as you'll see later going really

really fast and then smash them into each other and so this was very exciting I mean this has been done at other

places this has been done at the Tevatron as well protons I mean and you know perhaps that it's lack is one of

the one of the largest linear accelerators in the world and so this is

a new energy regime in which we attempt to do this much higher energies and so the first

time we tried to do this we're obviously very excited you can see that this is nearly a year ago today in fact just a

few days more excuse me and you can see the control room so we have a control

room outside above the surface of the accelerator in Geneva is packed that day

as you can imagine even Google was excited they they change they change

their famous logo for the day into into what you see at the bottom right here

it's not an accurate representation of what the accelerator looks like but it's it's close enough it got the message

across I think and there really wasn't anything being sucked in I promise all right so the the actual machine itself

came online in in really record time you can see what I showed you before was was

just was was at 8 o'clock and this is a this is a a beam a beam screen monitor

of just a few minutes before and they were able to send these protons all the way around this 17 mile ring almost

without a hitch and this all went off extremely well and I'd like to show you

what it looks like when when these two beams are brought together and the protons collide so I'd like to point out

the distance scale here is just millimeters and as soon as the accelerator operators bring these proton

beams into collision you can imagine them it's like firing two rifles at each other you have to be extremely precise

and you have to know exactly what you're doing so it's gonna play again I just want you to note that this is this is

fractions of an inch here and so they've steered these energetic beams of protons into one another and then suddenly what

what this graph is measuring is stuff coming out of this of this interaction point we've got this camera this giant

detector continuously looking at this one point in space and suddenly we start to see an extremely large amount of

activity excuse me coming out of this interaction and so this is the sign that protons are colliding and that the

physics that we're trying to do has started so the control room quickly

became a lot less fun after you can see here this a picture of of

various slack graduate students seated in the control room making sure things were okay while the senior scientists were we're

back in their offices looking at the interesting data but but everything was

happening very fast in fact this is the control room you saw just a second ago and on this side you have huge screens

and monitors which show you exactly what's going on inside the interaction point and that's what I'm going to show

you I'm going to describe to you exactly what we see when these protons collide with each other so I'd like to I'd like

to play this again because I want to because I want to highlight the last part of this little animation so you've

already seen the protons start to be accelerated in the what we call these booster accelerators and this SPS

accelerator before they get dumped into the Large Hadron Collider to really get up to the the energy and this really the

speed that we want but it's the last part of this in animation which is the most informative at this point because

it shows you what we're trying to do as the protons come in now that I've told

you that their energy of motion can be translated into mass energy what this

picture represents is the massive particles coming out of that interaction point and we we take a snapshot in fact

this is this is a simulated image but I will show you real images in just a second and these are particles these are

charged in fact protons in some cases electrons coming out and we measure their energy in their position in this

in this cylindrical sort of onion-like camera and that's that's what we do millions of times a second

so this is the detector this is the Atlas detector itself it's a hundred and

forty five feet long and 85 feet tall bigger than this building certainly bigger than a lot of buildings at on the

slack campus and you can see that it's it's made of a sort of onion-like design we have we have various cameras

effectively in three dimensions taking pictures in different ways of what's going on at that collision point for

example here's if if you stood on the detector which I don't advise and if you do wear a safety harness

you can see you can see the vast difference between the size of a person and the size of the detector itself

there's lots of different pieces to the detector that help to measure different things there are magnets here and here

there's an inner detector system which measures the position and other systems which I'll describe in a second but the

point is that we have to build such a large machine because the energy going into the collisions is so big that we

need enough space to measure what comes out so here's a snapshot sort of looking

down the barrel of the gun so to speak when we had it just all cabled up here's

the centermost piece in fact this is exactly where the protons collide and then you have various pieces in in

larger and larger radii coming out here you see a gentleman standing next to the the center and if you can imagine taking

a slice of this detector like a pizza slice just from the end on perspective

then you would see in cartoon form this picture and so this is actually what the

detector is comprised of as you move out from that interaction region so these

are the sort of three-dimensional you know many megapixel cameras if you want to think of it that way

which allow us to take these snapshots and what they can do is for example this innermost piece which itself is composed

of three other pieces helps us to measure the position of particles coming out you can imagine that if you want to

find out whether it was a proton and an electron you need to first figure out where the heck it was and so that's one

of the first things that we do is these particles come out from the interaction point so you can see here that a photon

wouldn't even leave a track in this because it's not charged in fact these these detectors measure charged

particles like electrons but then we have a set of detectors which measures the energy which measure the energy of

the particles in fact you can also measure a little bit of the position they're not as precise as as the detectors devoted to measuring position

but they do give you another piece of information and that's how much how fast effectively depending on the mass the

particle was when it came out of the interaction region so you can imagine that if you have a very interesting event you might get something shooting

out of the collision point whereas a lot of stuff sort of just passes through and is it very interesting we

have to throw it away and that's weak and we do that by measuring the energy and saying yeah you know that wasn't very high energy we we don't have enough

USB disks to save this so we're gonna throw it away at the outermost part of the detector we have something that

tries to sort of catch the particles which make it through the rest for example the muons in fact it's

devoted to measuring muons and it's called the muon spectrometer because it again measures position and and momentum

in fact so now I'd actually like to show you the actual events that we see in these collisions and what we're learning

from them so this is you'll see a couple of these this is our sort of quintessential event display so this is

just a single proton proton collision and the particles which have come out of that interaction region and the tracks

in the this the traces that they've left in our detector so let's dissect this

this this image from our from our megapixel camera you have as I mentioned at the innermost region you have a

position measurement device and so we get what we call tracks and here it's

it's devoted to measuring charged particles like electrons that you know you know the concept of you know static

electricity and and rubbing two things together and positive and negative charge and it's exactly those same

principles which allow us to measure the position of particles as they move through the detector but then I

mentioned the muon spectrometer and so just outside of the detector in this particular event there was a particle

that made it all the way out and left and left traces of its energy in these

detectors and so we've signaled the presence of a muon in that case and then

lastly you can see these clusters of energy here and here for example which are also in this two-dimensional sort of

unfolded view of the detector which represents something that we call a jet so you can actually see this by eye if

you just take a careful look you your eye kind of picks out a sort of cone like structure it's sort of a spray of

particles coming out of the interaction region so I'll describe what that is in in in more detail in a second but now we

have sort of a general way of looking at these events you sort of know the components that are that are at play

here so we can start to do some physics so in fact I told you to remember the Z boson

right so one of the things that that we know the Z boson does is to decay to two

muons so remember there's this system at the outside of the Atlas detector which is devoted to measuring muons and in

fact in this event that's exactly what we see so we expect the Z to decay to two muons it doesn't last very long it's

very heavy but the muons last a lot longer so we can measure those and so that's exactly what happened it's it's

cut off here but you can see in this bottom picture which is sort of a slice on the edge of the detector you can see

that these muons came out of the interaction point and left traces in the muon detector here and here and there

were also several jets in this event which I'll come back to in a second and so I'd like to actually animate an event

like this to show you the whole sequence of events from start to finish so here

here we start in the in the Large Hadron Collider accelerator and we go around in fact you just saw we went under the

French and Swiss border dip down into the into the accelerator itself where

it's actually the quarks inside of the proton now this is a real event this actually happened these come into the

detector and then as soon as they enter and collide you see exactly what I told you would happen you get a spray of

particles coming out of the interaction region you can measure their position their energy with the outer detectors

and the presence of a muon but then you can zoom in and we can put the pieces back together we know we know

what we measured and based on their properties we can figure out what went into it so here we see that there was a Z boson

which in this case instead of decaying to two muons remember I told you muons are just the essentially brother or

sister of the electron in this case the Z boson decided to decay to two electrons and so we've measured the

energy of those particles in the calorimeter x' we've measured the position of those particles in the tracking detector and we've put the

pieces back together and we've inferred the existence of the Z boson in in a single proton proton collision so this

is this is exciting at least for some of us and but but what this allows us to do is

it allows us to make detailed measurements of the properties of particles in many different ways not just to Z boson the Z boson is just a

very good example because it leaves very nice signatures in the detector but you can make a graph of the properties the

kinematics of these particles coming out I told you we measure the energy of the electron right I told you we measure the

momentum of the muons well we can put that information back together and we can make this graph or suddenly at

certain locations when you look for muons you see a peak for the Z boson and what this peak corresponds to what's on

the x-axis here is the mass and so what we've done is we've actually measured the mass of the Z boson by looking at

the energy or the momentum of the particles it decays to because they essentially carry information about what

the parent particle was you can do the same thing for example in the event I just showed you with electrons and so

again at the same position you see the mass of the Z boson and so these are

detailed delicate measurements that can be done across a very large range of energies and you actually see many other

particles in this spectrum in particular one I'll mention later is for example the japes eye which is a particle which

was at least co-discovered right here at SLAC and so all this entire spectrum is

is kind of like picking apart exactly what has gone in when these protons collided because of what came out and so

these measurements show us that there are massive particles which are being created when the protons collide now

this is kind of old news the Z boson was discovered in 1983 but the point is that

we're using this information to then look for new particles and that's exactly where we're going next but I

need to explain to you what these Jets actually were and so for example remember that the proton is made up of

these quarks but the quarks themselves are held together protons the table and

the desks that you're sitting in front of our just flying apart spontaneously they're held together the protons aren't

simply decaying now the quarks interact via a force called the strong force but

you can think of it and this isn't necessarily the best explanation but it's a useful one of these being held together by Springs

so you know that when you compress a spring you're it's it gets more and more difficult as you compress it more and

more you're putting energy into that spring and if you pull it apart hopefully it doesn't break in your hands

depending on how big it is that might hurt your car or bounces up and down when you drive down the street depending

on what kind of suspension system you have my old car certainly does and what you see is that the spring like for

suspension essentially prevents the quarks from flying apart but now we're colliding them we're colliding them at the speed

of light and the energy that you're putting in is essentially breaking those Springs apart and again just like

Einstein told us that energy can be used to create new particles when those Springs break and so this is what ends

up happening you break these springs apart but new particles are created in the process so you get this you get this

regeneration this spray of particles coming out just like you saw by eye you saw this cone like distribution of

particles in the jet and and that's exactly what we're talking about so here again is another image in fact this is

the one on the poster for the for the talk today and you can see just what I

was talking about you have a spray of particles coming out you have measurements in the calorimeter and in fact this corresponds nearly exactly

with what we expect from from the picture on the right side here so these Jets of particles tell us again about

the fact that there were quarks it in the in the proton proton collision now

what we can do this is another picture of two Jets is we can look for a heavy particle just like we did with muons and

electrons we can say well I know that there are pieces of the standard model of it are missing I showed you that you

know we think that there are particles there that we don't know quite a lot about and so can we sense the existence

of these new particles or for example can we see if there's pieces inside the quarks themselves and so if you look at

events like this where you have a jet on one side and a jet on the nother the other side this might be because of the

decay of a heavy particle right I told you that Z bosons decay into electrons and muons why can't a new particle

potentially decay into quarks so this is one of the first new measurements that we've done and in fact this set one of the world's

best limits on the presence of these new particles already this has happened in in just the last couple of months so by

making remember I showed you that that spectrum of mass from the Z boson right or other particles as well but related

to the electron decays and the muon decays you can do the same thing for the quarks so you see here a graph of the

the reconstructed mass of these quarks that that have come out and formed Jets but then you look inside you don't

really see any bumps from the Z boson we saw very clear peak in the spectrum from the J psi we saw a very clear peak why

don't we see any peaks here well if there is a new particle then him we must not be sensitive to it yet and so what

this graph tells you is it says that if there is anything there it's much harder to find than what we've looked at just

in the first few weeks of the experiment so we're still working on this but it tells you that we don't see a bump like

this and therefore if there's a new particle it has to have a mass much higher much further off the end of this

spectrum then we've we've collected in just a few weeks all right so so this is

actually one of the first new results that we've we've established this moves beyond this pushes the envelope further

and allows us to make statements about the the world in which we live but we

can put all of this information together I've told you about muons I've told you about electrons I've told you about Jets

how we've used jets to search for new particles I've also told you about what we call the top quark and this particle

is very interesting in and of itself now this event I'm gonna lead you through and then tell you what's interesting

about it so try to follow so first we have a muon here we've measured this in

the muon system it's very clear you can see it in this display on the right side here so we've seen this particle we know

what it is good but we also have an electron in this event we have an electron which

whose energy and position we've measured on this side we also have a couple of jets so we know how to use jets we know

how to put them together with the other information in the event in order to ask questions about what happened and that's

exactly what we've done in this case and in fact this combo nation of particles and some measurements about their energy and

momentum in particular tell us that we've seen exactly what we expected from a top quark decay I showed you at the

very beginning these two top quarks coming out of the proton-proton collision and that's shown here and here

but just from theoretical principles Michael in his colleagues will show us

that on one side we expected jet on the other side we expect a second jet I just

showed you that we've seen two jets in this event we also expect a muon on one side and an electron on the other when I

say side I'm just referring to the two different top quarks which we produce so

this theoretical picture has been shown experimentally in a very complicated situation we've used all the pieces of

the detector to prove that this is actually happened so this is the direction that we're going we can use

this information so we've we've now measured masses and cross-sections that is rates that which these things happen

and we can put this all together to search for new physics I'd like to point out one last thing in particular because

it's been in the news recently and that's that we have the ability to collide lead ions together so instead of

just colliding individual protons you can essentially collide bags of protons in the form of an entire nucleus all

right so instead of a single proton you have hundreds in this case right so here we have to lead atom lead atoms which

have been stripped of their electrons so just the ion the nucleus itself and it's collided and you can see the debris of

particles left behind this is obviously a simulation but what the idea here is

that I've told you about the sort of nature of quarks right they want to stay together they have these spring-like

forces holding them in inside the proton but at the beginning of the universe at the very first seconds of the universe

it didn't have to be that way it was so hot and so dense that it's possible that these things were free individual

particles now this comes this brings us full circle to the idea that the LHC is

allowing us to look back at the earliest times and tell us about the earliest stages of the universe when instead of

being locked together into protons and and neutrons and other maisons by the

strong force they could have been set free so we can try to recreate this sort of primordial soup by colliding the lead

ions instead of just individual protons and we've done exactly that and I'd like to show you an actual collision this is

quite dramatic if you compare to what you just saw a second ago so again you have in this case the lead ions coming

together and now they're going to collide in the center of Atlas but instead of just a few tracks you see

thousands so you can remember the picture that you saw a second ago where

you just had a few pieces of the detector lit up but in this case you have the entire color imager that is the

the energy measurement device full of energy you have the the position position measurement I'm gonna play it

one more time you have you have the position measurement device or the tracking system completely full of

tracks and what this is allowed us to do is it allows us to make detailed measurements of exactly what happened

when these lead ions collided and in a way and in fact results that have kept

me awake for the last week show us that this is in fact telling us new things about the this the nature of the cork

gluon plasma or this primordial soup which was potentially present at the very earliest stages of the universe so

here you can see just a head-on view like the one I've been showing you of the cork soup itself you can see that it

is completely full you have energy measurements all around the outside of the detector and in fact you can see

that the energy is completely distributed throughout the calorimeter system and this actually tells us once

you look inside this in more detail that there are things going on there which tell us how this cork gluon plasma this

soup actually operates and so this is actually potentially one of the one of the more interesting discoveries and

measurements that we've made in in recent times at the LHC I'd just like to point out that this is actually this

particular event occurred just a couple weeks ago and in fact just over the last week or two we've made some very

interesting measurements related to this which if you're curious I can show you a slide theme so I've

brought you through a long set of interesting measurements that we've made

but I haven't really told you about the Giants whose shoulders that we're

standing on to some effect and so here you see a timeline or over the last half century we've really been putting

together this picture that I've tried to describe to you we've discovered particles in bubble chambers or in cloud

chambers we've discovered several particles here at SLAC we've discovered particles at Fermilab at CERN and and

other places around the world and this is what has given us the confidence to make the measurements and interpret the

data that we've seen but in fact in just a few months we've effectively repeated what has gone on over the last half

century in order to reassure ourselves that we know what's going on and that we understand the picture that we've

painted over the last half century because in order to move beyond that you need to have a firm foundation on where

you stand and so that's exactly what we've been doing we call it sort of rediscovering the standard model sort of

rediscovering the universe that we know in order to establish signatures of

things that we don't know and so there's a long road ahead of us we've taken baby

steps so far and we have a lot of big steps to take in the years to come

the end of the of the physics run this year and next after the holidays will

hopefully tell us a lot of new things when we're able to analyze the data that we've collected so far but we have a

whole host of theories that we'd like to test and ask questions about I've told

you about I've told you about the supersymmetry this this mirror universe that might exist we're already starting

to probe the potential existence of these mirror particles I've told you about the Higgs particle this is a bit

more difficult to discover and we expect that over the next few years as we collect data and understand what we've

measured so far we will become sensitive to new things like the Higgs extra dimensions I described to you this is

one hypothesis as to what might be the reason for gravity acting the way it

does and so this is really decades of understanding and discoveries about the

universe in which we live that lie ahead of us so just to summarize I've told you

a lot of things I've told you that we've essentially discussed that we've essentially mapped out the world in

which we live but we know that there are pieces of that picture which don't quite fit we know that there are missing

pieces in this standard model of particle physics and we are already trying to understand that today the

instruments that we've built allow us the opportunity to test to this picture to look beyond that which we know and

honestly this is taking place at the highest man-made energies ever created we've already rediscovered how well our

standard picture works and as I mentioned with this picture of the Jets we're already even moving beyond it

we're taking steps beyond that which we've already been able to establish and looking further we're able to validate

some of the most complicated physics we know of to date this top quark picture which I showed you took potentially

decades depending on where you start counting to truly understand and and piece together all of its components to

make these measurements and we've already been doing them in just the first few months so for the next decade

the LHC is is really expected to continue to deliver science at the energy frontier providing both precision

tests of what we already know and I've showed you that we're already conducting them and hopefully putting together and

and discovering the pieces of the universe which we think we know are missing thank you

so David thank you very much we do have time for questions now please wait for

eager please wait we have two guys David

and Wells here with microphones that Dan I'm sorry Dan and wells with microphones

so what I call on you you'll get the microphone and wait for that before you

ask your question so let's start with this fellow here and you're next just

two questions so what's the highest energy level the LHC's hope to attain and why does the hick not higgs not

interact with photons but it does with neutrinos but it does with neutrinos okay so they said that's a very deep

question yes so so the the question was what what is the highest energy that the

that the Large Hadron hopes the Large Hadron Collider hopes to attain and the second question I'll repeat in a second

so the current energy that we're running at is what we call 7 TeV so an electron

volt is the energy that an electron gets when you when you accelerate it through

one volt of potential difference if you have a battery of one volt and you let the electron go from one side of the

battery to the other it will have one electron volt all right we collide the protons it's seven trillion electron

volts seven tera electron volts or TeV now this is actually half of the design

energy that the LHC has expect is is meant to achieve that's fourteen T the

reason for not doing this is because of certain instrumental effects which if somebody else asks I can show you a few

slides on and so it's basically at this point a safety measure the magnets which

I showed you those blue that blue tube that the protons accelerate around is actually kept it in almost absolute zero

it's colder than outer space and so what happens is when you accelerate the protons around there's a small chance

that one of these protons goes into the magnet instead of into the collision point it's a small chance but it's there but

what that means is it could heat it up a little bit and when you heat up something which is kept at Absolute Zero and which has lots of superfluid liquid

helium inside of it there's the potential for doing some damage and so as we understand this this actually goes

back to understanding our tools and methods as we understand more about how the machine works we will raise that

energy in fact when we turn when the the machine turns back on at the after the winter holidays it's expected to raise

the the collision energy from 7 TV to 8 TV for example so the second question

was why does the Higgs boson interact with neutrinos and not with photons and the reason is for the is because of the

demarcation essentially of forces there's there's the sort of electro weak

sector and and other sectors and the photon simply by by construction doesn't

couple to the Higgs field ok there's in fact I would defer to theorists for for

why this this happens at a more fundamental level but the I think this is beyond maybe the discussion here we

could talk about it afterwards but there is a difference between what the particles are that are Neutron neutrinos

in fact other leptons and the force carrying particles the Z boson for example and the photon itself they're

their different sets of particles and this they simply don't essentially talk to each other

if there are six types of quarks in your diagram show that there are three of them comprising a proton what are the

other ones do or is it always the same ones that are the proton and if I make go on then if the top quark weighs 200

times as much as a proton then clearly it's not one of the ones that's in there and is it only then created from the

energy of the collision and instantaneously decays and does it exist in any other form at any other time

anywhere that is a wonderful question in fact I have answers to various components of it and I will repeat the

question itself so the question is essentially if I have this table of six quarks why do you only see in fact two

of them in the proton only the up and the down quark are present in the proton

naturally so to speak okay so I'd like to go back to this plot

here so there are there are six different types of quarks and so the

question goes on to ask then how does this differentiate how do these the quarks in the proton differentiate from

other quarks for example the top quark which is so much heavier so these are this is there's multiple questions

inside there so the first point is that the I mentioned a few times on my

apologies without explaining very well particles called Mazen's for example these are different cousins of protons

and neutrons which are baryons these are just categories and physicists like to pretend that we're ancient Greeks and

and give them strange names and so but these other the the reason that you only

have the two types of quarks in the proton is that they're the lightest ones so the up and the down quark are

essentially the lightest quarks out of that family and because of equals

mc-squared if you have something that's a little bit heavier you can often turn it into you can decay it into lighter

particles okay and so what can happen what happens is that the stable particles protons are made of the state

most stable quarks they up in the down quark but the other quarks can form particles like the chaos can form

particles like the Omega can form particles like vaccine so this or cascade depending on

how you liked it so these do form other particles um in fact you have a particle

studied and discovered here at SLAC called the J psi which is made out of the charm cork okay and so the charm

cork is one of the I can just go back to the table for people who are would like

to to visualize this there we go so so

here you have the charm quark this is in the second group of of corpes so they

typically group up and down in this in this table so up and down quarks often go together

charming strange quarks often go together and top and bottom quarks often go together and that brings us to the answer to the

question of the top quark why is it so different that is a fundamental open

question in science why is the top quark so many hundreds of times heavier than

the other quarks it's something that even has a name it's so famous that we don't understand it's called the

hierarchy problem why is there this strange ladder event of masses inside

this table and in fact in the other in the other tables as well we don't know the answer to that question however

there was a part that we do know the answer to and is what does the top quark do since it's so heavy you I think

hinted at the answer which is that it decays almost instantaneously but we

remember I told you that the that the table here often is grouped together up and down the top quark will decay to the

bottom quark they're in the same so-called doublet disregard that comment

anyway and so what happens is it decays into the bottom quark and a W boson so

you'll get these particles coming out so if I go back to the to the plot that I Ono if I if I go back to the plot that I

showed you

there in fact what this shows you is precisely the answer to your question the top cork has decayed into this B

cork the B cork because it's a quark forms these Jets of particles I told you

about those guys that's here but then it also that the cousin that it decay the the boson that

it decays to is called the W boson and then that in turn because it is so heavy decays to other particles called the

muon and the neutrino does that does that answer most of your question what

do you mean we're in instant instantaneously uh-oh so yes part of

your question was how do we produce the top quark nature produces it nature can

produce it in highly energetic collisions so in fact all the time there are cosmic rays from stars and from

particles that are accelerated in out in the universe that collide with the upper atmosphere so it can be produced there

this is more related to the question of black holes but it can be produced up in

the upper atmosphere but again this is going to decay so fast that it's going to turn into a shower of other particles

long before it reaches the surface of the earth so on the earth in our everyday lives the only place that this

particle has ever produced is in a particle accelerator yeah it's a real mystery why we have all these species

that seem to not live anywhere in the universe and decay very rapidly stars

ordinary stars don't have enough energy in them to produce a top quark

get off the black my question is about the detectors yeah these bubble chambers or sure any

confrontation detector or what what's the nature of these detectors you have

great question I actually planned for that one okay so this is this is the 87

megapixel camera at the heart of the Atlas detector this is this is actually

a piece of this detector has been an integral part of the contribution that

slack has made to to the Atlas experiment as a whole in fact we've worked on the innermost part slack has a

lot of expertise in designing what we call vertex detectors I've told you that we have to recreate and measure the

positions of these particles at the very heart of the collision and that's exactly what this so-called pixel detector or silicon pixel detector does

this is just like well not just like related to your digital camera remember

we all I don't know Black Friday anybody go shopping anybody but buy a digital camera

yes probably bought a 14 megapixel camera 15 megapixel camera what that

number means is how many millions of pixels are on the chip which allow you to image whatever light is coming into

the the focal plane from the from the lens of the camera but what we do here is we set up those

pixels in a sort of sort of soda can like a cylinder and we give them various

layers so in fact here's the pixel detector and instead of your camera which has just one layer and that's why

you get a two-dimensional picture we have three layers and that's why we get a three-dimensional picture we can

measure how far out it's gone as well as how long what position along the detector it's been created and so sorry

yeah I lost I lost the gentleman who asked the question ah yes

yes so this this in particular is solid-state and then as you move outside of that there's another silicon or sort

of solid-state if you will detector which is made of strips so instead of individual little sort of

squares or rectangles that are each read out individually here you have just strips of digital camera like material

and then outside of that we have a drift chamber and so this is this is along the lines of the cloud chamber that you're

talking about but it's different in that we measure the passage of particles through the gas and then we measure the

ionization or the electrons right so you we don't have any excuse me we don't

have any off detectors in in the Atlas detector other experiments around

other experiments besides CMS that that are more dedicated to specific measurements do have to rank off

detectors wow that's not true we have a detector at the very end of Atlas which

is not used in any of the measurements I've shown you except to detect that a proton has gone by and that does use a

Trank operation yes in most cases yes so

we measure things by a ionization primarily and scintillation light in

some cases as you move further out but yes most of it's based on electronic signals so here we have the Atlas sort

of thermometer system or the calorimeter now this has two main systems the innermost system here is the

electromagnetic calorimeter that uses that is primarily dedicated to measuring

photons and electrons or things which interact and leave electromagnetic radiation but then in addition there are

you know if you had a proton which is passing through here instead of just a photon or electron it's also going to

interact via the strong interaction or sort of nuclear interactions and so we have another component outside of that

called the hadronic calorimeter now the liquid argon calorimeter this is why I mentioned the ionization and the

scintillation light because it has liquid argon so it's argon cooled down to a temperature at

which at which point it becomes a liquid and as particles charged particles pass through it it leaves ionization it

knocks electrons out of the atoms of the of the liquid argon in the in the in the

liquid and then we measure that on electrodes and then the tile calorimeter is is called a tile because it's got

pieces of plastic plastic tiles inside you can this you can almost imagine that

each of these little slits is a piece of plastic and as particles pass through the plastic it creates light and then we

measure the light using a light detector which are actually represented by these little green dots up at the top here and

so we put all of the pieces together both ionization scintillation light etc

to measure the energy in that particular case bent based experiment or is this a

continuous reproducible predictable experiment and what does what role does

probability play in potentially sometimes it will decay one way and another time it'll decay another way

that's the end it's that's the answer yes so it's so then how do you know specifically what the nature of matter

is except that it's a probability it's not an actual existence of a particle well okay I mean that's a little bit of

a philosophical question can only as philosophical ones not knowing enough it's a good thing I studied philosophy

so I'd like to go back to the mass distribution plot that I showed you so

the way that we kill the way that we construct this plot is not from a single event that's why when I and maybe I

didn't quite say it right but that's why when some of these events were shown there was the word candidate on it there

was the word you know possible you know top court candidate event because I'm an event by event basis you can be fairly

certain that that's what happened but there's the possibility that you made a mistake there's the possibility that there was even something there that you

didn't quite understand yet but the point is that when you collect a whole series of such events you can make plots

like this where this is unmistakable where you where you have a peak at a very particular energy and in fact the reason that this isn't

just a single point coming way up it has some spread right the Z we don't always measure the Z boson with with exactly

ninety one point six GeV we we have some error on that measurement because we

measure things with the calorimeter for which the electrons signal coming out may be always wasn't perfect because

when we measure the position of the muons in this in the tracking detector maybe it wasn't always perfect and so

yes we are we are a probabilistic beast in terms of how we how we understand the

world but I would like to claim that the world is probabilistic yeah I just like

to comment it um we are here deeply in the world of quantum mechanics and Einstein was wrong God does play dice

and you just have to deal with it okay

let me take two more questions and then we'll break so I'll stick around sir please the top quark has a mass of

about 173 GeV and Fermilab has already eliminated that as too large mass for

the Higgs it has to be less than 160 and more than about 110 yeah GeV that would

mean the Fermilab has actually detected them but haven't said so what's your

comment on that no that doesn't mean that they've detected remember I showed you this plot where I said that we

looked for something and didn't find it right here and so that's setting what you call a

limit and because of certain experimental peculiarities there's more

sensitivity by the elected by the Tevatron experiments in that particular mass window if Higgs boson had 170 GeV

they would have seen it but if it has 120 GeV they might not have if it has in

fact you there's another piece where if it's above a certain energy a certain

mass they wouldn't have seen it also and so it's what's called an exclusion limit and it doesn't mean that they've seen it

it means specifically that they haven't seen in a particular place when you sum or

attempt to sum the mass-energy x' of the products of the single proton collision what fraction of the input energy comes

out oh that's a very what can you account for that's a very good question well wow there's a lot of pieces to that

so a very small fraction in general we put in as I said before 7 TeV but

oftentimes what we measure is just a few hundred GeV now these these numbers are

three orders of magnitude different GeV is a billion TeV is a trillion so what

I'm telling you is that there's often we often only see in the interesting particles of you know 5 10 % of that

energy and that's because a lot of it remember that it's the whole proton which has 70 well that the collision of

the two protons is 70 V each one has three and a half but it's carried between three quarks so so you have to

divide that up first of all between the quarks and then all of that momentum all of that energy is it always transferred

okay again partially because it's probabilistic so the short answer is a

few five 10% for the interesting events and almost nothing for the non interesting events absolutely okay

otherwise I'm out of a job okay well as you probably see you could we keep David

up here talking all day but I think I'd like to release you folks however some

of David's colleagues Bart Wells where are you and Dan will stick around

they'll be stay here any questions you

have we'll talk to you privately and but let's thank David again for a beautiful time

and we'll see you all in January