so good evening and welcome to this evening slack public lecture last month

we celebrated the 10th anniversary of the first beams at our x-ray laser which

is out there in the slack accelerator yard you've heard those of you who've

been here before I've heard a number of lectures about results from this machine but it's a big deal now it's 10 years we

had a celebration in April and actually these couple public lectures surrounding

that are devoted to results from the LCLs the x-ray laser that we've created

here today's speaker is sebastian bootay

sebastian grew up in quebec went to McGill did his PhD work at the

University of Illinois and that work involved the study of the structure of

protein molecules using x-ray diffraction imaging that gave him a

little taste for the subject of biological imaging with x-rays and as

you'll see this device the x-ray laser allows us to be kind of a mecca for that

study and so finishing his ph.d he came here he joined actually what was the

lead up effort to that which took place at the daizy laboratory in Hamburg and at the same time began developing the

equipment which is needed to explore the structure of all kinds of different

biological molecules here at SLAC so without further ado let me introduce

sebastian and he'll tell you all about that topic sebastian thank you very much

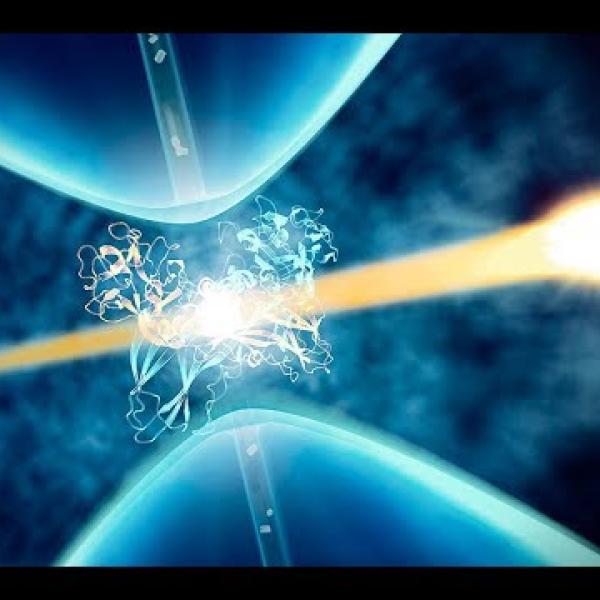

thanks for coming the plan for me today is to try to give you at the end of this

presentation give you an idea of what's behind this complicated pretty picture here at the front this is there's lots

going on here and my intent here is for you guys to walk away knowing all the

little parts that that make up an experiment that allows us to study biology in action so just as a quick

introduction of the main goal of what we're trying to do here in this field is we're trying to see the molecules of

life in action that is what we're trying to do and we're trying to use the x-ray laser to achieve that goal

so what is shown here is a collection of biological molecules that that we're all

made of and all life is made of and some have very important roles and everything

like we all are as made of atoms and we're trying to understand where the atoms are what they are doing and try to

deduce from that what is the function of all these molecules that that keep us alive so examples here that are pretty

obviously well known by mostly everybody is a virus everybody knows that viruses

can be bad for you but our body reacts by creating antibodies to to counteract

the actions of viruses other molecules shown here are acting in myosin that are molecules and your muscles that allow

you that perform actions that contract and expand your your muscles that allow you to move and here a ribosome is a

molecule that makes all these other molecules makes all other proteins by

interpreting DNA and and RNA so this

this is what we're trying to do trying to see where the atoms are what they're doing and try to ultimately make movies

to understand the function and biology in action so what is shown here is a is

a simple locking key model of interactions between biological molecules where you may have a certain

molecule potentially something that does something bad in your body and then some

drug that might have been designed that plugs perfectly into a little cavity in this molecule and in

order to design a drug like this you need to understand the shape and function of the molecule first and I'm

gonna talk about how we tried to do this what is shown here this will come up a

little bit later is is the number of structures number of such molecules that have been solved over the years and

there is a big ramp up that coincides with with the creation of some of the machines that are like like an x-ray

laser that I'll be talking about a little bit later all right so you know

at first if you think about this you know you know biological molecules

people you know life is very fragile you know x-rays are in too large of a quantity is are not good for you right

when you go to the dentist they make you wear a big lead suit to make sure that

you know your internal organs are not exposed too much so you know x-rays not

very good for fragile materials that make up life also if you do a quick

search online for for x-ray laser one of the first things you'll find is the type

of original ideas for an x-ray laser that was more like a weapon a space weapon in this case where you could use

an x-ray laser to to shoot down other targets in space so you know we're

talking about space weapons here we're talking about x-rays that are fundamentally damaging to life how does

that how does that mesh up right how does that make any sense to to have to

have such a machine to study life so I know how does something like this make sense a space weapon and a big laser how

can you use that to see what the molecules of life so hopefully I can

explain to you guys a little bit how that is possible so first let's take a

step we'll step back and quick explanation of what x-rays are x-rays

are fundamentally like light like every the light that you see so this is the so called electromagnetic spectrum really

all different wavelengths of light the visible light that we can see is in this range here lengths of about

a millionth of a centimeter or so x-rays are just like light but with shorter

wavelength so this range over here is what we're talking about x-rays are

defined roughly as the range matching the space between typical spacing between atoms in in solid materials so

that's why x-rays are a good tool to see where the atoms are their wavelengths

matches the spacing between atoms very well most people are familiar with with

what x-rays typically do they are very penetrating and through self material

and it allows you to see differences in intensity or material this is the first x-ray picture ever taken back hundred

and twenty four years ago so this is the

hand of the wife of the man who first discovered those x-rays back then so as

I said most people are pretty familiar with what x-rays do and this is you know another typical human subject this is

actually me right here but so as you

probably guessed this is not me but this is however me so a little bit about me

and my background with x-rays so the introduction stated what I did as a PhD

so I was working with x-rays every day trying to develop tools to help study biology new tools and you know this

happened to be at the same time while I was in grad school you can see a nice long fracture here clean break and you

know 11 screws later my arm is functional again so no harm no foul and

it was mentioned that I grew up in Quebec I'm a french-canadian so I'm a

walking stereotype I'm a French Canadian hockey player so this is me at Illinois

playing hockey and this was after my arm was all healed up the following season

so but yeah that's that's how it happened happened to me while playing hockey so as I said I'm a I'm a typical

French Canadian hockey player big surprise all right so

now light interacts with matter right we you see me you see other people here

light bounces off surfaces then we detect it with our eyes light will

interact with matter in different manners some that we are very familiar with like a reflection like reflecting

off of a mirror for example like can also be deflected passing through an

object like is shown here and different wavelengths or different colors wavelengths and colors are the same

thing will be deflected in different ways this is called a refraction process

like can also be absorbed and re-emitted or irradiated means the same thing like

can also be diffracted bouncing off objects and then we try to measure the angles at which they are deflected and

understand the structure of the object that light bounced off so those are typical interactions of light that allow

us to develop multiple tools to study matter at the atomic scale I'm going to

talk mostly about diffraction and how we use that to do deduce the shape or

position of the components that are too small for us to see with our naked eye

now that was mostly a wave behavior of light but light also behaves sometimes

as particles you cannot infinitely divide the energy of the light that you see into smaller

and smaller chunks a certain wavelength as a minimum size that is the smallest size that smallest amount of energy that

can be they can be divided into and we call those the particles of light

photons so when those minimal units of

energy from from light here the material and that amount of energy matches

perfectly say the energy the binding energy of an electron and an atom then

you can knock out this electron so basically particles can the particles of light didn't come in and they can knock

out some of the real particles inside the material and then you can have energetic electrons that come out and

now those wreak havoc on the especially biological materials that's what happens in your body if you're yet

irradiated too much with x-rays you knock out a lot of electrons from the atoms in your body and then those walk

around bounce around and they cause further damage to to other parts of your

body so we call this the in this case here if you shine light on on a metal

and knock out some electrons we call this the photoelectric effect and and

one thing that surprises many people is this is what Albert Einstein won a Nobel

Prize for the photoelectric effect not relativity this is what he yeah this is

what he got a Nobel Prize for so I'm talking about this here because we use the wave nature of light to study where

the atoms are but there's a consequence to that that the same light that

interacts with the sample also causes damage and we have to worry about that when we do our measurement we have to we

want to use the good properties of light to study the nature of material without

destroying what we're trying to measure so this theme will come back again a

little bit later all right so what we try to do this is shown simply and

conceptually here is we can picture every atom in a material as a slit in

this case a hole in a plate where you have a wave of light coming in and as the wave passes through a small hole or

is refracted off of an atom it changes the distribution of the wave in this

case it goes from a planar wave to a circular / vertical wave so if you

measure the the pattern of light on a detector a certain distance way you will

be able to deduce that this is a spherical wave and that there was a single point object at this location so

it all starts from that very simple principle if you have two such holes or

two atoms now those two spherical waves those two round waves here are going to interfere with each other it's gonna change the

pattern if we can measure this pattern we can again use that to deduce that yeah there were probably two different

atoms that were this distance apart that are interfering with each other so that's the principle we use to try to

study where atoms are now it gets and detailed a lot more complicated in this

as you add more and more atoms but the principle is the second we have lots of these point sources that interfere and

we can deduce from that from the way they they interfere with each other where the atoms are so if you take this

a step further and you have a real material in this case table salt that

that we're all familiar with so sodium chloride is the chemical composition of

table salt where atoms of sodium and chloride are alternating in a regular

pattern we call this a crystal and so if you have a crystal with a regular pattern like this when the light gets

deflected off this crystal it will create intense spots at varied well

defined periodic positions the periodic nature of the material will cause

diffraction a diffraction pattern on a detector that is also periodic and then

we can use this pattern to deduce that the structure of table salt is a crystal

with this alternating pattern so that's sort of the first the first example of

crystallography from a long time ago from William Lawrence Bragg and we

called these peaks of intensity here Bragg Peaks after him and so we that's

what we try to do with with biological material we tried to we basically

replace each of these points here that I have a single atom with a very complicated molecule like I showed a few

slides ago and now the pattern becomes much more complicated but we can still deduce what each of these points are

like and find where the atoms are within each of these points so this is what we

try to do it in what we call protein or macromolecular crystallography where we

try to create a crystal from one of these molecules a protein a virus or whatever this is this can be a

tedious process trying to to take a protein and crystallize it it does not

always work out but if you can do it then you end up with one of those diffraction patterns with lots of these

spots here these intense spots of more intense light more intense x-rays then

we can deduce computationally the where the electrons are from this pattern and

from that we can try to fit a model an atomic model where we know that this pattern looks like a certain a certain

pattern that that we know exists in proteins or such molecules and then we

can build a model that best represents this structure so that's that's what we

try to do and what is shown again on this plot here is is the explosion of

this technique of macromolecular crystallography the the blue part of the

curve is what the structures that were deduced from crystallography and the green and red were from other techniques

so crystallography has been a very very successful method to try to understand

where atoms are in the molecules of life so that can be a little tedious of time

but it's very very successful and and it shows by you know the hundreds of

thousands of structures that have been deduced what has caused this this great

explosion of structures in and you know and the late 80s Early 90s are these

types of machines that would call synchrotron x-rays sources synchrotron light sources they are electron

accelerators where electrons go around a ring and as they curve around the

electrons get accelerated and electrons that are accelerated will emit light and

if you build a machine the proper parameters you'll the light that will be emitted will be at the x-ray range so

you can get all these beam lines and you can dedicate a few to to studying biology

and some of the bigger machines have up to 60 beamlines operating at a time and it can be a kilometre in circumference

there's just a few examples shown here and each of these there's about 50 such

machines around the world now and they range from over a kilometer like these

two to two a little smaller this one is in Francis ones in Chicago for example

they are everywhere and they're really the workhorse of understanding understanding biology understanding what

the atoms are doing and where they are and this is what such a measurement

would look like this is one angle you have to rotate the crystal this one

crystal at the start of the measurement and you have to rotate it to measure all different angles but this is what one

such pattern would look like but as I said earlier those those those molecules

of life here are sensitive to two x-rays they you cannot put them in an x-ray beam forever they will eventually get

damaged this is what we see it's such a synchrotron source as you expose the

crystal longer it starts to get destroyed this is what happens after a while where clearly has changed you've

clearly damaged the sample and the high angle intensity spots disappear you see

these spots here go to a much higher angle from the center and those start to disappear and the higher angles give you

the finer details so as you start to lose the higher angles you lose the

information after so as I said earlier we use x-rays to probe the structure of

matter of those molecules but we want to do it in a way that does not destroy what we're trying to see x-rays give us

the information we want but it also destroys the information we want in

order to in order to to minimize this damage what is typically done is you you

freeze the crystal liquid nitrogen you freeze it - to slow down the propagation

of this damage it still happens it still will happen but you can slow it down by making those those damaged

particles diffuse slower by freezing the motions out this is not ideal for this

works great as I said but it's not ideal because you end up looking at the the sample not in its natural state

freezing something at liquid nitrogen temperature does not give you the natural environment of the molecule it's

it's not at the temperatures of life it may freeze the sample in a position

that's not natural right in the same way that you know it's a sort of a Sur like

this right so you don't want to see Han Solo frozen this is not in the natural position once all right you kind of want

to see him chasing a stormtrooper or something this is not necessarily telling you exactly what you want to get

at right it gives you pretty good information you can see his face and everything but you know it doesn't tell

you what it does and it might be a little bit different at room temperature compared to freezing it so you know

we're what x-ray lasers afford us in one way is to avoid the need to to cool down

the sample and look at the sample at more natural life conditions all right

so this is what the x-ray laser looks like very different from the round machines that I showed earlier right so we have a synchrotron here on sight

it is one of the small ones because it's one of the first ones ever it's over here it's relatively tiny compared to

the very long straight accelerator that we use to make the x-ray laser this

accelerator has been here for 50 years or more it's that started in the early 60s

construction started in the early 60s it has been repurposed about 10 years ago to use the last kilometer of the three

kilometers to make x-rays where we do experiments hit two separate buildings where we use this x-ray beam so that's

not obviously a very different machine from from a one of those round synchrotrons they showed earlier I

mentioned earlier that when you accelerate electrons they will emit light that is

an unavoidable physical property of charged particles like electrons so as

you accelerate them or wiggle them check wiggling them like this is like accelerating them because you changed

their the direction in which they're moving then electrons will emit some

x-rays if what makes an x-ray laser is different from other machines is how

tight this bunch of electron is and how long these undulating

magnets alternating now north-south poles that make the electrons wiggle

back and forth this is very long this is 130 meters for us here so as you start

to emit x-rays at the beginning those x-rays will re interact with the electrons further down the line and they

will cause them to bunch up at the end it's a very hard to see here I apologize for that but they end up with what we

call micro bunches and all these micro bunches really what they are is in the end is that all the electrons move

together rather than moving a little bit out of out of sync they all move together and it behave like one very

large charge and that one very large charge when you oscillate it back and forth makes a very very intense short

pulse of x-rays so long story short here we we end up with a much brighter beam

these are the synchrotrons we talked about these are x-ray lasers 10 orders

of 10 not 10 orders of magnitude more than than before which is 10 billion

times more intense than than previous 10 million times more bright than previous

sources so all the x-rays come in a very short burst on the order of one

millionth of a billionth of a second and that allows us to do some some unique

measurements with such very very very short short pulses of x-rays as was

mentioned earlier this is the 10th year anniversary and we had a party not so long ago so 10 years ago this was the

first ever x-ray laser beam every man and and you know I said we had a big get

together where we remain it real - about the good times and bad times and and you

know I'm gonna show you a few results of what we've been doing in the biology area using this machine alright so I

still haven't quite told you why the most powerful x-ray beam in the world can work for studying fragile biology

and this is shown schematically here how

this can work rather than have a very very long pulse of x-rays the pulses

from those round machines that I mentioned are very long like thousands of times longer than what you see here

this little pulse here and so as you illuminate your sample with these x-rays

they start to change and you start to measure a damaged sample later on if you

make this pulse very very short here the what is shown here are units of femtoseconds and those are the millions

of a billions of a second that I mentioned earlier so very very short the

x-rays can go through the sample before there's any time for anything to move the simple conceptual way to picture

this is the x-rays passed through the sample during this pulse at the speed of

light while the damage that happens the changes that happen afterwards happens at the speed of sound the speed

of light is is 300,000 kilometers per

second the speed of sound is on the order of 300 meters per second very different so the x-rays go through at the speed of

light the damage happens at the speed of sound a little bit no oversimplification

but you know for the most part a good explanation of what happens so very very

short pulses of x-rays and then the sample is just obliterated that allows

us to put way more x-rays in this short pulse than we would be able to do in a long pulse allowing us to get much

better clearer images by packing all these x-rays in a short amount of time that would not be possible to do if if

the measurement was longer so those of you know who Keyser söze here

when I think of this site think about what he says he goes and just like that poof it's gone and it will never be seen

again after that so best movie ever my favorite movie

ever so in practice it looks looks like

this we we have x-ray instruments where we deliver the beam to multiple systems

to make these measurements so those are some of the scientists setting up an experiment and you know once in a while

even I do some work over there but it looks very complicated to the naked eye

to the to the untrained eye but it's conceptually very simple there's lots of

lots of shiny metals but it's actually very conceptually simple which I will show on this slide here so all we're

really doing is we take the the x-ray laser beam so x-ray free electron laser

beam we take it we use mirrors to focus it to make it smaller to take the x-rays

and pack them into a smaller area so we focus the beam to a certain point where

we have a sample in this case being delivered in a flowing liquid jet so we

just cross the beams right here and then we measure the this diffraction

as I said measured the angles at which the x-rays are deflected they all come in on a straight line and then we

measure these the where at which angles those bright spots are and then deduce

the structure from there so I said conceptually very simple we take the beam focus it hit the sample with it

measure it on on a camera an x-ray sensitive camera reason not not that

different fundamentally from your iPhone camera and do this multiple times to get

all different angles and and try to get a structure out of that what is shown

here is what we called it what we call an LC P injector it's basically a grease

injector it's that that mimics a little bit the the fatty

membranes of cells some of the most important molecules in your body are at the boundary between the inside of your

cells and the outside of your cells to to let the right stuff pass through or react properly to external external

signals so those membranes we call those membrane proteins there are in the

membrane of the cell they they don't like to live in water they like to live in a fatty environment like the cell

membrane and this LCP here this fat matrix is a mimic of cell membranes it

it creates an environment that's similar that and then the crystals can grow directly inside this matrix here the

crystals are not shown here but they grow within these pores and this fundamentally limits the size of the

crystals and so the smaller the crystals are the more prone they are to get damaged quickly at one of those round

machines that I talked about earlier where you have a long illumination you you're putting a lot of x-rays on a

small volume it will get damaged faster so this perfect case use for our

facility here for the x-ray laser crystals that are too small that we can deliver at room temperature in a

basically native environment much more suited to understand the true structure

and true function of those molecules so this is one of the results that I'm

gonna I'm gonna show right now so this is a recent result where we studied this

is one of those membrane proteins here so this is a simple representation of of

one of those proteins and this is a melatonin receptor melatonin is a

molecule shown here it's a it's a small molecule that that signals to your body

that it's time to sleep or not basically so it is a very there is very common you

can buy melatonin supplements for for dealing with sleep issues our modern

world is not very conducive to having a a good day night sleep pattern with with

all that's going on and all the all the video games that you can play and so you

know lots of people are suffering from from sleep pattern issues and these

supplements here are one way to deal with it but you can imagine designing a

specific drug that is similar to that this is the melatonin shown here in yellow inside of this this this protein

that reacts to this the signal from the melatonin that says it's time to go to sleep and you can imagine designing a

specific drug that will that will go do this job better and deal with surn sleep

deficiencies better without causing side effects of having interactions with a

different molecule that looks similar but not quite the same and causing some some bad reaction with with some other

molecule so understanding the structure of these molecules and how they bind

together allows people to design new and better drugs and this is you know

billions of dollar industry for for that kind of work so we were not the the

scientist that came to use the facility here for this particular work they were not able to grow crystals that were

large enough to be studied any other way than with the x-ray laser and and this allowed us to solve to understand the

structure of to such receptors binding to melatonin so there's receptor 1 and 2

and they are very similar to some extent as you can see the blue and orange ones are kind of similar but they have some

minor differences and the work allowed us to understand how the the melatonin

goes in through this channel here in this case and the second receptor which has a slightly different function as a

second channel here that that is less understood wire what it does but this was studied with

melatonin bound to it as well as different types of drugs and and other

compounds and it really allows us to understand how those those two molecules interact with

each other and potentially design be the starting point for designing better

better treatments for sleep sleep issues

so this would not have been possible without the very intense beam that we

use here with the x-ray laser now one of

the other advantages of a machine like like the x-ray laser is the pulses are

so short the measurements are so short you can take a snapshot image of your

object nothing moves during the during the the measurement so you can imagine

starting a reaction by for example in

photosynthesis you can imagine starting a reaction by illuminating it with light

visible light starting a reaction and measuring the the changes with time by taking multiple snapshots so this is

what I'm going to talk about now where I'm going to talk about photosynthesis

I'm going to talk about how you know how our atmosphere got its oxygen so our

planet a long time ago had a lot of water this is a two water molecules h2o so two hydrogen's in white and one

oxygen if you have two such molecules then you put some energy in you can

produce two h2 molecules and two and one

molecule that has two oxygen atoms in it this is the air we breathe the air we breathe has got about twenty 21% oxygen

in it and our planet used to not have

really any Oh to in in the atmosphere and what has allowed our plant to become

suitable for us to be here is this molecule here called photosystem ii this

molecule does a reaction like this where it takes water and creates oxygen and

billions i don't know exactly part of a few billion years ago when this molecule

showed up on our plan it started to to transform water and pump a bunch of oxygen in the atmosphere

that allowed all the life that that we that we are all loved right now - huh -

eventually flourish and this happens by having four different photons four

different particles of light interact with the molecules sequentially to eventually take water and split it and

produce oxygen so you know easily be argued that this is one of the most

important molecules that on our planet for for life here it is it is believed

to have originally started in in bacteria cyanobacteria a long time ago

and eventually created the atmosphere that that we have and now it is everywhere in bacteria and all plants

and it continues to to replenish our atmosphere with with the air we breathe so very important molecule and a very

important process that is not it's not fully understood really this this for

for illumination forward light flashes cycle that creates eventually produces

the oxygen we breathe breezes is now well understood and having the ability to to look at these molecules at room

temperature not frozen with flash photography of the x-ray laser allows us

to to try to see what happens with in this reaction here and so I have a

little movie here that that will sort of show how we do this and so this is the

photosystem 2 molecule inside there there's a manganese calcium cluster

where all the action happens the word there's there's a few atoms of manganese and calcium and we can either deliver

the crystals inside of a liquid jet or shoot them on a little tape drive here and then illuminate the moon green light

either one two three or four flashes to go through this cycle and then

eventually shoot them at a certain delay after this this laser this light

illumination to to see when what state it is at that certain point and that allows us to

right now to have the beginnings of a movie a molecular movie of how this

molecule takes water and splits it to produce the oxygen we breathe so this is

a very important for a typical example of what we can do in terms of measuring

room temperature dynamics of of important molecules to to life all right

so this those are the only two examples of the biology that that we do that I

will show and then I will show you what

I consider spectacular movies of what of what happens after this x-ray illumination as I said the x-rays come

in they completely obliterate the sample but amazingly you still have time to

take the the measurement that you want even though this happens after your measurement so this is a liquid jet that

you'll see that flows from right to left this little white line here is actually a flash of light because the samp the

jet gets so hot that's picked up by the camera and the jet flows this way and

the x-rays are gonna hit here and you'll see what happens a millionth of a second

after the x-rays come and yet we have a clear image of of the the sample were

just in so the x-rays come in and they basically cut a hole in the jet that's a

hundred times larger than the x-ray beam itself so it completely vaporizes it and

explodes it and yet as I said all this happens after the you've been able to

make a successful measurement of a very fragile molecule so this is the beginning of the process here where the

x-rays come in they vaporize the water gets very hot and then this creates some

very high pressures that push the water away and then eventually it it forms

this big gap in the jet so as I said amazingly this happens even though we're we're able to

make a real measurement of the very fine details of the position of the atoms

were interested in this gap in in the jet here is is millions of times bigger than the features we're trying to

measure and this is part of the original figure that I showed I really need to

acknowledge cloud your standards now moved on to Rutgers University is this all happened these types of measurements

happen all because of him this these beautiful movies were really all due to him and so the x-rays come and they

vaporize some water and the water causes the jet to to separate and explode now

if you if you do this in droplets get a similar similar effect but I remember

before we made this experiment I predicted that the droplet that gets hit by the x-rays this one here would be

completely obliterated but the next neighbors would be perfectly fine and you will see how wrong I was about that

so you the x-ray beam completely blows

up that droplet it's completely gone and the pressure wave pushes the next neighbors to the point that if you keep

the movie play the movie for a little bit longer the three closest droplets

eventually all get absorbed into one droplet so this is this is the beginning

phase here where the x-rays hit vaporize the water again and then big shock wave

propagates and eventually completely pancakes the neighbors so that was

unexpected at least from me and actually not just for me because we previously

that a couple years before that we had a measurement on similar wall water droplets where we were interested to

look at the water structure itself completely unrelated measurement and this is what people thought happens to

drop it when you hit it with an x-ray laser beam like this where no the water

is just shooting out the side that you hit and this even made the cover of a very very reputable journal where we we

just got this artist during wrong here a few years later we showed that that that's not at all how

water droplets explode when you eliminate them with an x-ray laser be

one more movie for pure entertainment our very talented communications department here made a movie of a

collection of all these exploding jets pretty music I'll just let you enjoy it for 40 seconds

[Music]

so not to not to dwell on the point too

much here but what I find amazing is all this happens and yet we see where atoms

are as I said million times smaller features than these giant explosions all this can be done

despite this incredible changes that we see in the sample long after the x-rays

are gone as I said the the x-rays pass through the sample is speed of light this happens more the speed of sound

pretty amazing to me still that that that this works now I'll I'll take the

time scale even shorter here those movies happen on the the millionth of a second timeframe we're gonna go the

millionth of a billionth of a second time scale here and try to see how the sample can change during the timescales

of the x-ray exposure so this is a simple cartoon of how a sample can

change under x-ray illumination you can picture two different kinds of damage or changes with time what we call global

damage where everything just flies apart in sort of a uniform manner random

uniform manner and then after a certain time when your crystal is undergoing such a process you don't have a regular

arrangement of molecules anymore you don't have the fraction anymore because you don't have a regular array of

objects to diffract from so in that case your sample the fact for a while when

it's too damaged it'll just won't deflect anymore you could also picture different behavior

where you know not all the atoms are the same right some atoms are are heavier

than others and they will absorb x-rays more than others and you can picture that these areas will be more

specifically damaged than others and they will change faster than others and you'll still measure a diffraction

pattern that can be interpreted but some parts will change some parts won't and

now you have to figure out at what point our assumption that the sample is not changed

the measurement is no longer valid right so we devised an experiment to try to figure that out as I said before x-rays

that we use to to understand the structure of matter also cause changes

in it and nine out of ten x rays that we shoot at the sample actually cause damage only

one is diffracted for every ten that gets absorbed and causes that every nine

that gets absorbed and causes damage so it is is a big concern as we make the

x-ray beam smaller and smaller to look at smaller and smaller particles so as I

said we devised an experiment to try to study what happens on this femtosecond

time scale or the millionth of a billionth of a second time scale where this looks pretty similar why I showed

before we focused the x-rays in this case to a spot that's a hundred times

smaller than what I showed before but we can use the the x-ray laser to make two

pulses that have slightly different colors or different wavelengths of x-rays so a blue pulse and a red pulse

and we can control the time between them from 25 2 seconds to 100 femtoseconds

again femtoseconds being a millionth of a billionth of a second and we can separate them in color enough that if we

use in this case an iron filter after the sample we can have the blue x-rays

that come first be here and be totally absorbed by the filter and the red

x-rays go through this is the transmission through this iron filter here you have about 30 percent

transmission and here you have essentially zero transmission so that allows us to damage the sample with the

blue x-rays and measure the structure of the damage sample with the red x-rays so

compared to the movies I showed before the timescale of this is a billing is a

billion times faster basically so that that is the type of measurements we need

to do to understand if our assumptions that the sample are is not damaged or valid or not so we did that on a

molecule that contains multiple disulfide bonds so two sulfur atoms

there are neck to each other sulphur atoms are present in most molecules of life and they they

are heavier than the more typical carbon oxygen atoms that are that are more prevalent and so they are likely to

change more during the x-ray measurement and then other parts of the sample and

so this is what is shown here where we see a six frame movie of what happens

this is the what we see when we have no delay between the two colors and this is

what we see as we increase the time delay all the way to one hundred millionth of a billionth of a second and

basically what is shown here is in green is where the electrons are or where the

sulfurs are and in red is where they used to be by making a difference

between the zero delay and the longer

delay measurement so as you can see they just fly farther apart I said Green is where they're going and

red is where they used to be so with time those those two sulfur atoms are

clearly flying apart while the rest of the molecule is not changing that much so that definitely challenges our

assumption under very very intense very tight small x-ray illumination whether

there's no change in the sample or not so if you extract the distance between

those two sulfur atoms as a function of time here you can see that they fly apart somewhat linearly in a somewhat

straight fashion our typical x-ray measurements are about 30 M two seconds

here and you can see there's there's definitely a change a 25% change between in the distance of these two atoms and

that is very significant if you're trying to to understand the detail mechanisms of what this molecule does so

this is this is a big error if you have not accounted for it and if you

extrapolate this line and and and get a speed by taking this distance dividing

by the time you get roughly the speed of light so sorry the speed of sound as I said earlier the damage kind of happens

at the speed of sound so I like this pattern here because it's a reminded me of Mickey Mouse the first

time we saw it so anyway so as we tried to make the samples smaller and smaller

getting rid of the need to make crystals and try and do this with single molecules we need to pack more and more

x-rays into smaller volume and these types of of structural changes during

the measurement become more and more of a concern this is a another movie of the

ultimate experiment that we would like to do that we have attempted also a

little bit already the x-rays come down the x-ray laser machine here we have

single molecules single proteins floating in air being sucked into vacuum

where we try to interact them one at a time with an x-ray beam measure a diffraction pattern similar to the

crystals I talked about but now single molecules so the x-ray focus has to be a lot smaller we do this bunch of times

tens of thousands to millions of times depending on who you ask and then you figure out the relative orientation of

all these patterns and try to build your 3d three-dimensional scattering pattern

from this data and then you press the magic button in computer you get the structure at the end so this is

basically what we do with crystals now but we would like to do this with single molecules first work our way towards

smaller crystals then eventually single molecules that requires I said a much tighter x-ray focus that will be more

prone to causing damage so we really need to understand the those dynamics of change during the x-ray illumination if

we are ever to understand the results of such an experiment at the at the atomic

level seeing where every atom is and trusting the results so as I said we've

we've done some work on in this area this is very reminiscent of the movie that I just showed you see these

individual slices of the diffraction pattern you pieced them together and and

eventually try to get a structure this was a single large virus

as you can see the pattern is not complete there's lots of gaps between between these each of these slices and

so what I'm going to show you next is what we're doing to try to to try to

resolve the data sparsity problem as

well as as I already mentioned we want to understand the damage mechanisms so

we are about 80% through the construction of an of a new accelerator

and a new system that we call LCS - so this is a reverse view of the picture I showed earlier of LCLs we currently use

the one column last kilometer of the accelerator the first kilometer has been refurbished to be a superconducting

accelerator it will come online in 2021 and it will produce 1 million pulses per

second currently we operate at 120 pulses per second so a huge increase in the number

of pulses and now we might be able to do these very challenging experiments that require you know millions of images to

obtain structures from smaller and smaller objects eventually potentially single molecules so this is uh sort of

the next step and we are in a in the middle of a 15 month shutdown now where we're not running any experiments to

complete this construction here so a very big important project for us all

right before I summarize this just wanted to quickly say that I don't do this all by myself obviously and those

are some of the important institutions that that contributed to the results that I showed here so all right so it's

a quick summary here I hope I have shown you that x-ray lasers allow studying

molecules of life in action with improved resolution compared to more

conventional x-ray sources it has medical applications and understanding photosynthesis among many

others I only showed a couple but those two the you know the photosynthetic

cycle as well as understanding medically relevant molecules now they bye

- drugs are two very important areas that we are pursuing the sample is

completely destroyed but only after the image is captured that that is really amazing in my opinion as as we tried to

move towards single molecules and making molecular movies we require smaller beams which can lead to more sample

damage and more images which we can start to address with the higher repetition rate of LCLs - with millions

of pulses a million pulses per second and more studies are needed to understand where our assumption that

there is no damage fails I hope some of the results I showed drove that point

home for you guys so that's about it so this is what this is what we do here

this is what me and a few of my colleagues do we basically spend our

days trying to to improve devised methods to to understand the molecules

of life in action this is what we do and this this picture here shows a good

summary of what we're trying to do we're trying to get a structure of a molecule by flowing little crystals inside a jet

that gets completely destroyed by our beam but not fast enough to prevent us

from performing these measurements so I said this is what we do we study molecules of life in action every day we

come to work and we drive towards that goal and thank you ok we have some time

for questions please raise your hand get recognized you each have a microphone in

front of you so after you're recognized you push the button on the microphone it will light up red and then you can be

heard and also you'll be on the videotape so questions please

so the fact that the damage propagates it about the speed of sound is not just

an empirical experimental finding or is there some theoretical basis for it right well the sound is basically the

the motion of atoms you know pushing on each other right so so damage would be

the same thing when atoms fly apart its atoms pushing on each other and there's certain limit to how fast they can push

each other so that part is is roughly right the what is not right is the

subtle electronic changes to - to an atom each atom has gotten cloud of

electrons around it and those electrons fly apart much faster so a certain atom

can lose an electron much much faster than the speed of sound and that would be a much more subtle effect than the

physical blowing up of the object so those two the electronic damage is more

what we're concerned about then than them flying apart at the speed of sound which as I said is mostly right because

that's how fast things can push each other out of the way do you have to

worry much about detector damage from the x-rays yes but maybe not for the

reasons you might you might guess the the signals we're measuring are fine

they're there the detectors are pretty well matched to the intensity of those

spots of diffraction that we measure well we have to worry about is completely different

sometimes we shoot these jets into vacuum and a water jet in vacuum if you do something wrong with it they will

freeze the water will turn into ice and the diffraction from ice crystals is

much much more intense like a million times more intense and that completely

destroys our detectors sometimes when the experiment is running properly no we

do not have to worry about damaging the detector we do put a small shield in front of it to capture the debris that

flies at it so that physical damage could happen if we didn't have a debris shield yeah

I guess I've gotta add three accelerators of course come from

high-energy physics and also the detectors come from high-energy physics so those materials have seen much worse

than what you get in these experiments other questions when you show that

sequence of images representing the explosion of the sample I noticed that

most of all have a pattern of a double cone let's say but there are a few that

are different they seem like a fuse something like that I remember a green image for example right yeah okay so

that comes from let me see if I can we grab an image let me pause it in a spot

that would show

okay yeah this is a good one okay yeah so what happens here in this case is you

can only make a jet as small as the tube that the water flows in all right

that makes a wall and the jet comes out at that size and that's limited in size

by the smallest tube you can make that will not clog with whatever a piece of

dust so that's usually about 20 microns or 20 millionths of a meter all right we

can get around that by making a virtual tube by flowing gas around the liquid

and then the gas makes a virtual tube and if a piece of dust comes out it just pushes the gas down all the way and then

the gas tube reforms this is what's happening here there's a co flowing gas that basically folds this cone back

because it's basically wind is folding that cone back right right so it starts

out with a cone on both sides but then the wind that keep that makes this jet a lot smaller folds the cone of debris

back away from from the nozzle what

experiments until you do besides these atomic structure measurements yes what

else what else we do yes what else what

all other experiments we do that could be of interest besides just molecular experiments well we we have LCLs does

work in all sorts various material science plasma physics just chemistry as

well ultra fast chemistry some fundamental

atomic interactions trying to study the energy levels in in complicated atomic

systems binding energies and things like that so we have a biology is one of

seven roughly major areas of work that I'll see us the x-ray laser pursues I

question I think if you go to our public lecture website you'll find other

lectures on some of these other applications magnetism movies of

chemical reactions etc so have a look for that what you explained about the

damage how will it work for multi bunches in LCLs - because the first

bunch will destroy the sample the second sample won't have anything to look at right so that there's a very good

question those movies that you see here they they go on for longer than then the time for

the next pulse if we go a million per second that's certainly true for the big jet that I showed that I showed at the

beginning these smaller jets here you can accelerate them fast enough to to be

able to push everything out of the way before the next pulse comes at a million pulses per second you have to run them a

factor of five faster than this particular jet that you see here for example so you're saying the samples

will move south that the next sample will be there for the next part that is that is a hard

requirement for for these types of measurements you have to push the sample that's damaged out of the way to get to

a an undamaged part of a jet before the next post comes and some some jets or

droplets are not suitable for 1 million pulses per second they they are too slow

for doing that so let's just take couple more questions there was one over here

yes I had a question about the membrane protein experiment with the Italian receptor what is the resolution you were

getting in in those like 1 or 2 angstroms right I don't quote me on that

because I don't remember the exact number right this is it's on the order of two and a half to three angstroms

so an angstrom is is one tenth of a

billionth of a meter so typical atomic spacing of say a silicon in your

computer chip is about 4 angstrom so this is resolution smaller than your

typical silicon to silicon atomic spacing my other question was um and

this may not be applicable to what you do but have you thought about looking at a mixture of proteins by coupling your

injector to like a liquid chromatograph where we can separate a lot of samples and then have like another dimension of

separation in time and introduce them to your beam different times and then have many structure solved in a single run

yeah absolutely I didn't show this but this is a an area of active research to look at dynamics from-from rapidly

mixing two things together rather than using light to start a reaction not then

many things in life are light sensitive you and I are not particularly light sensitive most of our body most of the

reactions happen by two things reacting with each other and rapid mixing is uh we need to develop better mixing sample

delivery devices to really exploit that fully but there's been a few papers about that already and that's that's an

area that we expect will will grow thank you thanks for speaking I like the

jokes is there any direction or interest in applying this methodology to

neuroscience and how far away would that be yeah yeah there's there's been one

one paper published a few years back looking at a certain molecule involved

in synaptic reaction so it's really this is applicable to any structural biology

problem as long as it's it's a problem that really requires the unique

capabilities of an x-ray laser a lot of these problems can still be done at at those rounds synchrotron sources but you

know if the crystals are too small or if if there can be some dynamic mixing

involved then then we can absolutely be be of help for that kind of a problem

yeah where did the paper come out of I've came out of axial bronze group and

here at Stanford so Google I mean yeah it's a professor here at Stanford well

very good thank you very very much after the lecture Sebastian will be out

in the lobby you can ask him more questions informally until then let's

thank him very much and we hope to see

you all at the end of July for the next round of these public lectures so thank you

[Music]