michael peskin: I'd like to welcome everyone out there to the latest installment of the SLAC public lectures um we are hoping in the near future to see you.

michael peskin: Inside SLAC but for the moment it's still the pandemic and we're still in the pandemic schedule, but look i'm really glad that so many of you wanted to tune in for this what's going to be really a very interesting lecture.

michael peskin: The title of the lecture is getting to the core of the earth's magnetic field, the lecture is Ben Ofori-Okai, who's one of our new Panofsky fellows here at the SLAC laboratory.

michael peskin: Ben did his undergraduate work at Yale then he went on to do his graduate work at MIT, at MIT he worked with actually a leading group in.

michael peskin: instrumentation and radiation sources for various kinds of physical observations and he became one of the world's experts in producing what's called terahertz radiation.

michael peskin: Which is going to play an interesting role in this talk that you're going to hear about, then in 2016 he came to SLAC after he got his PhD.

michael peskin: And he's been working on a variety of projects, some of them with material science and the one he'll talk about today with the so called high energy density group working on extreme states of matter.

michael peskin: So he's going to explain to us roughly where the earth's magnetic field comes from and how to understand it better, and I think it'll be a very interesting talk.

michael peskin: Now, after the talk, we will have a question and answer session so if you would like to submit a question to the question and answer session.

michael peskin: Please look at the bottom of your zoom window there's a Q&A tab and if you hit the Q&A tab you'll see a box, that you can write your question into.

michael peskin: And then, at the end of the talk i'll convey those questions to Ben and the other panelists and hopefully we'll have time for some interesting discussion.

michael peskin: But right now it's for Ben, why don't you take it away and let's hear about the earth's magnetic field.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Right great so thank you, Michael for that kind and generous introduction i'd like to thank everybody who's tuned in to listen to this talk today, I hope that.

Ben Ofori-Okai: You learn something get something out of it have some fun with it i'd also like to take this opportunity to thank the SLAC public lecture committee for inviting me to give me a chance to talk about this work today.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So without further ado, I guess, we can get started.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Well, and I guess, I should say, before we before we get to the science, I wanted to take this opportunity to talk a little bit about myself and my history and sort of how how I got to SLAC.

Ben Ofori-Okai: This story is sort of a sort of a longer story involves and, like any good story, it involves it's a it's a good origin story involves a lot of people and the place i'm starting with is my is my parents.

Ben Ofori-Okai: My parents were born born in a country named Ghana, which is on the west coast of Africa sort of on the Horn of Africa, my dad is from a town called Peki.

Ben Ofori-Okai: My mom is from a nearby neighboring village called Kwehu and they grew grew up their lives, you know, the first 18 years of their lives there and then as any.

Ben Ofori-Okai: teenager who's finishing up school and is ready getting ready to start the next thing they decided they wanted to move away from home.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But, in a way that I think only my parents would do as some of the most intrepid people i've ever met they decided to move not somewhere super close by, but actually to Germany.

Ben Ofori-Okai: My dad left first he's a couple years older than my mom when he started his studies in chemistry in Darmstadt my mom joined him later working on her nursing degree, they eventually moved to Berlin.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Where my dad got his PhD and one of the things that I managed to find in preparing preparing for this lecture is an incredibly awesome photo of my parents and I think one everybody should have the joy of seeing my parents looking incredibly amazing.

Ben Ofori-Okai: and seeing just how they look at each other and how how clearly how much clearly fun, they were having while living in Germany.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so during this time, like I said, my dad got his PhD in chemistry and then my parents moved from Germany eventually to the UK to Great Britain and here i've sort of started the city of Colchester as a place of interest, because this is where I was born.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And then, not only a couple of months later, my parents relocated from Colchester to upstate New York City of Albany New York, which is where I spent the first 18 years of my life.

Ben Ofori-Okai: and growing up with my parents, I spent a lot of time imitating them, as you can sort of get from these photos, although I contend that it was my birthday and my dad was wearing my birthday hat so he's imitating me in this case.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But by scientific journey really starts here it starts with my parents and starts with them as.

Ben Ofori-Okai: As a pair of people who were very, very scientifically inclined of their own right, who really, really encouraged me and really.

Ben Ofori-Okai: believe that science was a thing that I could do, and so it's really because of them that i'm even in this opportunity I have this opportunity to present to you, so I wanted to take an opportunity to point that out.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So, as I said, I spent the next 18 years of my life roughly in Albany before moving on to Yale, this is probably the most.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Intense how it started versus how it's going. Ben Ofori-Okai: iteration or meme iteration that we're going to have and so that's a photo of me from kindergarten.

Ben Ofori-Okai: 13 years later I wound up at Yale studying chemistry, so my bachelor's and a PhD are both in chemistry.

Ben Ofori-Okai: I started doing research as an undergrad working in Charlie's group Al before moving on to Carie nelson's group working primarily.

Ben Ofori-Okai: On terahertz science terahertz spectroscopy and that's going, and then, when I graduated in 2016 as Michael said I wound up at SLAC in the high energy density sciences group.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And this is really where I started to learn about and think about the the topic or the the topic that's going to be the focus of the discussion today, which is the excuse me, which is the Center of the earth.

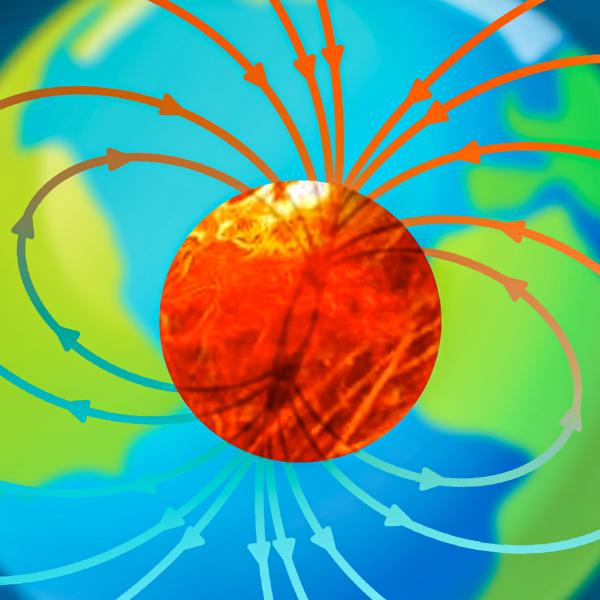

Ben Ofori-Okai: And how it produces how it's magnet and how the earth's magnetic field is produced, and so this graphic is sort of illustrating.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Some of the key players, so the core of the earth, the outer and the inner core the magnetic field that sort of being emanated from the core of the earth.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the talk today is going to be focused on trying to just get a sense of what do we understand about the earth's magnetic field now.

Ben Ofori-Okai: What don't we understand about the earth's magnetic field and its origin and some experiments that are happening at SLAC with me and some other scientists in the group and elsewhere to try and.

Ben Ofori-Okai: answer some of the questions that we need to build better models and have a better understanding of how this thing the the earth's magnetic field is produced.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so i've used the term magnetic field a lot going to use it a lot more, and over the rest of the talk.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so I figured it was probably it's probably a useful idea to just take a step back and define sort of concretely what the magnetic field is.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And to do that it's a it's easy, I think, to say or to start by thinking about what the magnetic force is the magnetic force.

Ben Ofori-Okai: it's a force of nature and it's a force that interacts that that that has interactions between moving charged particles, so this can be moving electrons are moving.

Ben Ofori-Okai: protons they can be moving in electrical currents like in wires like what would just like a wire, that you have lying around your house or anywhere or through through what's called a plasma.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the magnetic force also mediates the interaction between magnetic materials.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The magnetic field describes how that magnetic force will interact so describes how currents will interact with the magnetic field and how magnetic materials will interact with the magnetic field.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, this picture shows sort of how physicists like to draw this with the series of lines.

Ben Ofori-Okai: that connects let's see the North Pole in the south pole of a bar magnet and the lines indicate and the arrows let's say on these lines they indicate the direction of the magnetic field.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So the magnetic field, also has a direction which is going to wind up becoming important detail what's worth thinking about the earth's field.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now, this is a nice cartoon picture of how we like to think about this.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The reality is actually it, this is, but this is a representation and we can actually observe this and you probably have seen something like this.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Which is a bar magnet surrounded by iron filings, and here the the the iron filings are magnetic materials and they orient themselves in the shape of the magnetic field that's being produced by this bar magnet and again, maybe this is something that you've seen.

Ben Ofori-Okai: At some point in your life either playing with magnets or maybe maybe in school at some point.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so we also know things like you know the North Pole and a South Pole and North doesn't like North and North like South and all of these things, these are sort of the basis the basics of the magnetic field, or the basics of a magnetic field.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now the earth, it turns out, has a magnetic field that's just everywhere, if you so this map is basically showing.

Ben Ofori-Okai: What would happen if you took the magnetic material or like a compass, and you sat on the earth's surface and you ask where is the Needle, on your compass pointing.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And what we know is that it points, primarily in one direction at what's called the magnetic North Pole, which differs a little bit in position from where the geographic North Pole is that determines the access around which the earth rotates.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And, basically, regardless of where you are on earth, you can see that the the compass will always point toward magnetic North and so it's a useful tool for being able to orient yourself.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now, how strong is the earth's magnetic field right, this is, this is also a useful question.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the magnetic field strength is a number that's typically measured in units of gauss.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, so for for comparison here here are the magnetic field strength for some materials or objects that you may have interacted with at some point in your life.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The first is the inside of an MRI where the magnetic field strength is about 10,000 gauss.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And for reference, this is a strong magnetic field right you can't go into an MRI with a magnetic material the magnetic field will will rip it out of your hand or rip it out of whatever, and so this is, this is an example of a strong magnetic field.

Ben Ofori-Okai: A much more modest magnetic field again that you might have interacted with instead of a fridge magnet fridge fridge magnets field is about 100 gauss.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Right, and this is still strong enough to stick it stick an object onto your fridge or you know put up an announcement, or maybe your favorite drawing or something like that, on your fridge.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, by comparison, though the earth's magnetic field is pretty wimpy the earth's magnetic field is only about half a gauss.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But this is also, I think, interesting to just keep in perspective, the fact that the earth's magnetic field is so weak in comparison to all of these other things, and yet we're still able to detect it very, very easily using the tools that we have available.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now, as a as a group, as a people we've sort of known about the earth's magnetic field for a long time.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The some of the earliest recorded campuses that we've been able to find date back almost you know over 2000 years ago, or for over 2000 years ago.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And these were using ancient China, primarily, for we believe primarily for divination and and in parts of the practice of fung Shui.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And in this case, what it was used for what we believe it was used for was because the the whole principle of function way and requires you to orient yourself, for your surroundings.

Ben Ofori-Okai: In a way to maximize your harmony and so having a well defined direction by which you can tell Okay, you need to move yourself that's where you need to move, something that way that's what that's what we think the the sort of first uses of a compass was.

Ben Ofori-Okai: It wasn't until about you know, a thought over 1000 years later, that we started seeing navigational campuses again first appearing in China and then about 100 years after that.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Throughout Europe, and then the rest of the world, and then compass has started to be used for what we might be what you might be familiar with her have interacted with an accomplice in your own way for knowing which direction is North and knowing which way to go.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now it turns out that we have understood, we know about the earth's magnetic field we've known about it for at least last 2000 years, if not longer.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But it turns out that we really only understand the magnetic field, as it is now.

Ben Ofori-Okai: What scientists have been able to do, or what they've been able to observe is by looking at ocean floors.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And you can see regions where it sort of new rock is appearing through the crust of the earth and in this rock you find magnetic materials that are pointing in that direction.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And as you go further from the origin point what you see, is where these magnetic materials are pointing flips.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, in some cases, north is what we think north is now and in other periods of earth's history, it was actually on the other side, it was actually south.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so there's been what are called these geomagnetic reversals that scientists have been able to observe and then characterized over over time.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And we know that the earth's magnetic field flips every once in a while at a process that seems to be random maybe it's going to happen again soon, who knows it's it's sort of unclear, this is an open question in the field of of what exactly drives this process.

Ben Ofori-Okai: One other thing that we've learned over the last couple hundred hundred and 50 years or so, is that actually the position of magnetic North itself has shifted over time.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So in this plot taken from a from an article in nature, we, the scientists who've been tracking the position of the magnetic North Pole have seen that it's shifted over the last hundred years hundred and 50 years or so.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so we don't really have any evidence to believe that it's going to stop moving we don't have any evidence to believe that the the the magnetic field of earth won't flip again, and so this this sort of.

Ben Ofori-Okai: starts to you know beg the question of what is, what is the cause of the magnetic field, the earth's magnetic field, and why does it behave in this way.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now, in addition, we also care because the magnetic field, the earth's magnetic field does more than just protect help us orient ourselves as we're on the surface, it turns out that it also protects us from high energy particles that are being ejected from the sun.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The because the earth's magnetic field extends out beyond just the surface, these high energy particles that are that are spat out at US can be deflected that these higher energy particles, known as a solar, wind, they can be deflected by what's called the magneto sphere.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, this this protects us from these high energy particles interacting with us or harming us, but it also happens to produce one of what I think is the most.

Ben Ofori-Okai: cool and beautiful things in nature, which are the northern and southern lights. Ben Ofori-Okai: And just taking a moment to marvel at this photo, this is a photo that was taken by a person in outer space looking at high energy particles as they're.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Shooting across the surface of the earth or near the the atmosphere atmosphere in this case, these are actually the southern lights the aurora astrologers so the both the North Pole in the south pole.

Ben Ofori-Okai: see this phenomenon, and this is again, this is because of the influence of the magnetosphere in protecting us from this cosmic from these from the solar, wind and these higher energy particles.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now. Ben Ofori-Okai: Maybe one one other thing that I want to sort of leave you with at this point is that not every single planet in our solar system has a magnetic field, we know that, for instance Venus and Mars don't have planetary magnetic fields like the earth does.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And even other planets that do have magnetic fields, this sort of have very they can have very weird structure very different structure from ours.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So the earth's magnetic magnetic North Pole sits very, very close to the geographic North Pole.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But in the case of uranus and Neptune there's a much, much, much larger separation between the two.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And where we think the the field is originating is different from the Center of the planet, in the case of uranus and Neptune compared to the earth.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, this again starts to really make it an interesting question of what is the cause of the earth's magnetic field, why does it have the structure that it has why, why is it different from these other planets and what do we need to know in order to be able to understand this.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So. Ben Ofori-Okai: A little bit more history, the first ideas about the origins of the earth's magnetic field came from around 1600 this guy named William Gilbert who's also from Colchester.

Ben Ofori-Okai: He wrote this book called on the magnet on the magnet and the magnetic body isn't that great magnet the earth.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And he suppose that the earth itself was just a giant magnetic ball in the same way that you know you could pick up an iron rock and it would be magnet it would be magnetic the earth itself was just natively magnetic.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And then 1600 you didn't have any real reason to assume that that wasn't going to be true.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Right, we, the only thing that we knew that some materials were magnetic we knew that some materials weren't and we knew that you could you know pick up a magnetic material and you could use it to find other magnetic materials.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so that theory sort of persisted for a while, but over time, a scientist started to do some more exploration and they had gained better understanding.

Ben Ofori-Okai: We learned that this wasn't the case some of the evidence that sort of refutes this idea or the actually the geomagnetic reversals that I talked about a couple of slides ago.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The movement of the magnetic North Pole those things sort of don't align with the idea that the earth itself is just a giant permanent magnet.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But one other piece of information that was learned around the early 1900s by scientists me Murray and Pierre Curie who.

Ben Ofori-Okai: I would call my second favorite scientific power couple besides my parents and their combined work with Pierre Weiss and and what they.

Ben Ofori-Okai: discovered in their studies of magnetic materials as the following that if you took a magnet and you heat it up, regardless of whatever the magnet was at some point, it would stop being magnetic if you heat it enough.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And this is a problem because, even at this point scientists knew that the Center of the earth was very, very hot.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And there is Oh, and for every material there's some characteristic temperature called the Curie temperature, which is on the order of about 1000 kelvin.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And estimates for the temperature in the Center of the earth were much higher than that. Ben Ofori-Okai: So the idea that the earth itself was just this giant magnet again didn't really make sense couldn't you couldn't reconcile this idea.

Ben Ofori-Okai: With the the fact, with all of these scientific observations and so scientists sort of had to come up with a new explanation or a new solution to what they thought was the root cause.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And that's the starting point for this idea originates from an 1820 or a scientist Hans Orsted made the following observation.

Ben Ofori-Okai: That, if you took a wire and You ran current through it, so you pushed electrons through the wire it generated a magnetic field, and so this seemed to be the other way of generating magnetic fields, besides materials that were just intrinsically magnetic, and so this then began or became.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The starting point for the idea of how the earth's magnetic field can be generated.

Ben Ofori-Okai: One thing I want to point out is that the the strength of the magnetic field depends on how much current you're moving through the wire.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the shape of the magnetic field depends on how the wire itself is oriented, so in this is one example, but if you sort of bent the while bent the wire around in a bunch of different ways the magnetic field structure would look different.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Right and so fast forward about 100 years when Joseph Larmor, or he was thinking about the sun and he's thinking about the earth, and the fact that they both.

Ben Ofori-Okai: might have magnetic fields and he writes a couple of papers thinking about this idea.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And in these papers, he supposes that what's happening is that at the Center or near the Center of a planet.

Ben Ofori-Okai: You have this fluid motion, you have emotion of a fluid inside the Center of the planet and then that fluid is electrically conductive in the same way that a wire as well, like when you're passing electrons through it.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And that this motion of the planet, the fluid inside the planet can create a magnetic field in the same way that the wire is creating a magnetic field and that's the cause that that's the source of the earth's magnetic field.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And that ideas with sat around for a little while. Ben Ofori-Okai: Until and in scientists sort of we had inklings about of ideas at this of why this could be true, but one of the most important pieces of evidence came was was sort of discovered and confirmed about 15 or 20 years later, based on earthquake data.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And to explain this, I want to describe one particular. Ben Ofori-Okai: property of earthquakes, which is that when there's an earthquake, there are actually a bunch of different kinds of waves that are produced that travel through the earth.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And in this case the two most relevant ones are going to be what are called primary or P waves, which are compression leaves and secondary waves waves or shear waves.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now a primary wave is like I said it's a compression wave, and what that means is that, as the wave is moving through your material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The material is compressed and expanded in progress and expanded, and you can sort of think of it as like the the the what's happening when you're playing an accordion right and you see this expression this compression and expansion of the space between your hands.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And shear waves or secondary waves in that case the motion of the materialism like a side to side motion.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And then, this this the way one way, you can think about this as if you imagine ever playing if you've ever played a guitar and you sort of strumming a guitar in the string vibrates up and down it's that same side to side motion that you that you're seeing in an shear wave.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now compression waves will move through a liquid but shear waves won't and that's The thing that scientists knew.

Ben Ofori-Okai: and taking this information and combining it with another observation which was that, when there was an earthquake at some point at some location on the surface of the earth.

Ben Ofori-Okai: There were places where you could measure P what you could measure, where you could measure both P and S waves.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But some locations where you wouldn't measure s waves you'd only measure P waves and in the late 1930s, as a scientist Inge Lehmann put the whole thing together and realize that what this meant was that the Center of the earth had a liquid outer core and a solid inner core.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, this provided again a really important piece of information that was used to support the idea, this idea that the earth was producing its own magnetic field through this thing called a dynamo.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now, the idea of this dynamo was further advanced by the scientist Walter Elsasser, and Eksasser's dynamo theory assume that you needed three things.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So one you needed a fluid that would conduct current like electrical current to that there was going to be some source of energy and that energy would be provided by the planets rotation around its axis.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And lastly, we needed an energy source at the Center of the earth to drive convection to drive basically the the the movement of hot fluid away from the Center and then eventually back towards the Center as it cools off.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And we learned about the last thing, are we having, for instance, and lasting also thanks to appear in the Pier and Marie Curie because of their work on radioactivity.

Ben Ofori-Okai: We had, and we had some we have some understanding about the fact that it's a fluid at the Center of the earth, and so we need to answer some other questions in order to be able to figure out.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Whether or not the dynamo theory is accurate, so, in particular, what we need to know as scientists are one, what are the conditions.

Ben Ofori-Okai: At the earth's core so how how our material what what conditions to materials experience, we need to understand the phase of materials that at these conditions so, for instance, whether or not they're solid or liquid and how they how they behave.

Ben Ofori-Okai: We need to know how well these materials conduct electricity. Ben Ofori-Okai: And then we also need to understand how well they move heat and if we understand all of these things we can plug numbers and and and.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Make inferences on how how the behavior of the earth works and by consequence will hopefully be able to better understand how the earth's magnetic field is being generated.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Okay, so to start to answer the first question we know now that the as we go into the Center of the earth that there's multiple different layers.

Ben Ofori-Okai: right we live on the on the surface, on the crust below us there's a mantle and then the outer core and the inner core.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And depending on where you are in these layers there are different you expect you experience different one would experience different material compositions.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So the mantle is mostly made of silicate rocks and the outer and inner corners, have a lot of nickel and a lot of iron, as well as some other elements sulfur oxygen and other lighter elements as you get towards the inner core.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So you might say, okay Well, now that we know what these materials are we could just measure their properties and then see.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Okay, did you know, is the is the outer core conductive enough to make sense for the dynamo theory, but the challenge is that these materials are under extreme temperature and also under extreme pressure.

Ben Ofori-Okai: and pressure in this case that the pressures that we're talking about at the Center of the earth are they are just are just extremely intense.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So the scientific definition of pressure is it's a force applied over an area.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The standard unit is Pascal and for reference if you put your hand on $1 or on a table you put $1 bill in your hand as i'm showing in my visual aid above me that's one Pascal of pressure being exerted on the palm of your hand.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now the pressure that we routinely experience just on the day to day as one atmosphere of pressure which is 100 was just a little bit more than 100,000 pascal's.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And maybe as another point of reference, if you put a four or five pound weight in your hand that the pressure that you're experiencing there is.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Is a 1% of an atmosphere so .01 atmospheres.

Ben Ofori-Okai: By extrapolation you'd have to put 400 pounds in the palm of your hand to experience one atmosphere of pressure just on your palm.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And if that sounds like a lot, the pressure at the Center of the Earth is even higher than that at the Center of the earth we estimate the materials are experienced 3.6 million atmospheres of pressure.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And one way that I would like to think about that is holding 360 billion dollars in the palm of your hand and once you've gotten over the euphoria of holding 360 billion dollars you'd also realize that you're under this immense pressure from all of that weight.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, so one so it's important to realize that we're not going to be talking about materials as we necessarily think about them, but under these very, very extreme conditions.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And we also know even from our own experiences that materials can change their behavior and they can change their properties under extreme pressure.

Ben Ofori-Okai: One of the most common examples that you might have heard about as carbon which at room temperature is graphite that's the stuff that's in your pencil that you used to write with.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But if you expose it to 2 million atmospheres of pressure and raise the temperature a bit it transforms into diamond.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And these are two, this is, these are examples of two very, very different kinds of materials right graphite is opaque.

Ben Ofori-Okai: It absorbs light it's a very, very soft material it's easy to bend it's easy to break it's why you can use it as a to write things as pencils.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Whereas diamond is transparent right light goes right through it and it is the hardest material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the only difference that we've the difference in when these two phases are most stable.

Ben Ofori-Okai: is just how much pressure they're under and how much temperature at how much temperature they're experiencing.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, even if we understand how, for instance, carbon behaves under atmospheric pressure and standard and room temperature that doesn't mean that we would understand how carbon is going to behave up conditions at the Center of the earth.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So in starting to try and understand or try and develop an idea of what we need to know.

Ben Ofori-Okai: We can think about or we can take examples of the materials that we're going to find that these various different layers.

Ben Ofori-Okai: and ask well how do we know, do we know how they behave under high temperature and high pressure and so here this plot is showing what's called a phase diagram.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the phase and then in this particular case it's the phase diagram for iron and when i'm plotting on the X axis on the horizontal axis is pressure and millions of atmosphere sorry and the y axis is temperature.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And we can see that even at a low pressure so atmospheric pressure just raising the temperature the iron will go from one solid phase called a bcc phase, or a body centered cubic phase.

Ben Ofori-Okai: into what's called an FCC phase, or a face centered cubic structure and this already told these these names imply that the way that the outcomes are arranged.

Ben Ofori-Okai: In the crystal is different, and if you keep ramping the temperature up even more eventually melts into becomes a liquid, but as you increase the pressure where you expect these transformations to happen as a function of temperature changes.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And then, this orange box i'm showing the conditions that we estimate the earth's core outer core to be in terms of temperature and pressure.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, if we want to try and understand materials and how they're behaving at the earth's core, these are the conditions that we're going to have to try and subject, for instance, iron to or nickel or any or anything else that's in the outer court.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So how are we going to do that. Ben Ofori-Okai: And it turns out that one of the ways that you can subject the material to very, very, very high pressures and temperatures is using lasers and a technique called laser driven compression.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the way that this works is that you take a very small piece of sample in this case the sample is.

Ben Ofori-Okai: A 10th of a millimeter in thickness. Ben Ofori-Okai: And you coat it with a very, very thin piece of plastic and then you shine a high energy laser called the drive laser onto the plastic.

Ben Ofori-Okai: This causes the plastic to explode and in the force of that explosion it launches what's called a shockwave.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the shockwave is sort of like your earthquake on steroids right it's it's really high intensity really high energetic way that's moving through the material at speeds faster than the sound speed.

Ben Ofori-Okai: For reference the sound speed and air is about 300 meters per second the sound speed through aluminum is about 10 times that so 3000 meters per second and shock waves and aluminum can travel at almost 10,000 meters per second.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So we're talking the supersonic waves that are moving through the material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: In our experiments these thin these very, very thin materials are the sample that we're interested in.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And as a picture as a point of reference, but you can see here, this is a grid of many different samples, and you can the arrow that's pointing to one of them is just pointing to one of the squares, which is one of the samples.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the the main. Ben Ofori-Okai: The the larger dimensions of this sample are about three millimeters by three millimeters and, if you would, if you could turn it on its side and be able to see the thickness that thickness is the.01 millimeters that's the thickness of the sample.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Okay, so going back to the shock waves after we've hit the laser onto our later launch the shockwave into the material the shockwave just propagates through.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And what it does, is it changes it takes the material from an initial pressure temperature in density to a different pressure temperature and density.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the conditions for that were worked out by these two physicists William Rankine and Pierre Hugoniot.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And what they determined was that Okay, if you know the initial temperature, you know the initial pressure, and you know the initial density of the material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: You can figure out what the final temperature, the final pressure and the final density will be based on the the shockwave speed, so how fast the shock wave is moving through the material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, this means that for our experiments knowing what the shockwave velocity is is a really important parameter because it'll tell us where we are or what state we've driven the material into.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now, thankfully we've developed scientists have developed a technique for measuring this it's called the the the main technique is a is called visor.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And what it is, is it's a velocity velocity velocimetry measurement and the way that it works is that you take a green let's say a green laser a much lower energy green laser than our drive laser and you shine it on the other side of the sample.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the sample is going to be reflecting light the whole time and when the shockwave moves and hits that interface you'll see a change in how that light is reflected.

Ben Ofori-Okai: and based on that change, then you can infer what the velocity of the shockwave is that's moving through the sample.

Ben Ofori-Okai: This is a, this is a technique that we use all the time and characterizing our shocks.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And it's important here to realize that, for these measurements number one we're using a very, very, very tiny volume of material right like I said the thickness of the sample is a 10th of a millimeter or hundreds of a millimeter excuse me.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And these shock waves only exist for 1,000,000,010 10,000,000,000th of a second or a nanosecond.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And then afterwards the sample is just destroyed like it's just gone. Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, for these measurements, that if we want to make any we want to do any interrogating of what the material is like how it's behaving or whatever we need to make sure that we're doing it on a timescale that's short shorter than how long it takes for the sample to blow up.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But this is also convenient, because it means that you don't need to make this giant vat of.

Ben Ofori-Okai: of material and raise its temperature and apply a lot of pressure to it in order to reach the conditions of interest for our experiments are for our studies.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So Okay, now that we know that we can drive a material to extreme temperature and extreme pressure, we want to check to see whether or not that material is electrically conductive.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And again just to orient everybody, I want to very quickly describe what we mean by electrically conductive by comparing two kinds of materials and insulator and a metal.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now, in an insulator the electrons are stuck between atoms in bonds or in bonds between the atoms that make up the structure so one example again that's actually the same example that I had before, as diamond diamond is an electrical insulator.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And by comparison and electrical conductor is a material, where the electrons can move freely between the atoms.

Ben Ofori-Okai: An example of that sort of material is basically any metal so copper aluminum silver gold, these are all very, very typical are these are these are sort of standard examples of conductors that you might have seen or interacted with just at any point.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the way that you can tell whether or not the material is an insulator conductor is also pretty simple it turns out that you just have to connect it to a battery.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so what a battery does is it effectively applies a force which will move the electrons through the material will try to move the electrons to the material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: This generates what's called a current and that's just a measure of how many electrons are moving in a second through a piece of material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: and its measured in amperes now, scientists have a quantity, called the conductivity which is just a measure of how easy it is to move electrons through a conductor.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So we say that a good conductor has a high conductivity, meaning that a lot of electrons will flow if we apply a battery to it and an insulator has a low conductivity which means electrons won't flow through the material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, this is just how this is sort of the easy way to check to see whether or not a material as a conductor an insulator basically to check to see whether or not you can push electrons through it.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now, in these experiments, it turns out that there's another way to figure out whether or not something is an insulator or a conductor, and that way involves using light.

Ben Ofori-Okai: In my one of my favorite scientific techniques which is called spectroscopy. Ben Ofori-Okai: Now spectroscopy I find cool for a bunch of reasons, not one, not the least of which, from the fact that it derives from the Latin word for ghost and the Greek word for to see so it sort of loosely translates to seeing ghosts.

Ben Ofori-Okai: i'm not like a ghost hunter kind of person, but given that my initials are boo I sort of have an affinity for the technique.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, and it sort of really is that it's sort of taking light shining it at an object which maybe you can't see so easily.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And then, by measuring something about the light you learn something about the object and that's sort of that sort of crazy on its own.

Ben Ofori-Okai: It also means that any any anything that can see sort of by its nature, is a spectroscopy.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And, primarily the difference between you or I as a casual spectroscopy just watching this watching netflix watching whatever.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And being quantitative and what we're trying to do is how we're what we're trying to understand is how quantitative are we, and what we're trying to measure.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so things, one can try to measure or things that can be useful are things like whether or not a material is just giving light, so does it have a color.

Ben Ofori-Okai: If you shine light on it, whether or not the light is reflected or transmitted through the material and how much light is reflected or transmitted.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And all of these things can be used to characterize different kinds of materials and, in particular, we can use it to classify whether or not something is an insulator or a conductor.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Because one other thing that we know about light is that it's an electromagnetic wave and that and that property allows light to push electrons around in a material, if there are electrons that move.

Ben Ofori-Okai: When electrons can't be moved through the material actually the light will just pass through it.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so what this means is that if you have an insulating piece of material and you shine light on it like will go through it, this is why windows or windows, this is why windows are made of glass which is an insulating material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: On the other hand, something like a metal, which has a lot of free electrons when the light hits the the sample the electrons start to move and that causes the light to be reflected.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And this is why mirrors are mirrors, this is why mirrors are made primarily out of metal because they have lots of free electrons and that's a really easy way than to reflect a lot of light.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So an insulator will transmit a lot of light and reflect very, very little, whereas a conductor will reflect a lot of light and translate very, very little.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, this is already a useful tool that we have for being able to determine whether or not a material is insulating are conducting, and this is how we're going to be able to use spectroscopy for figuring out whether or not an immaterial scintillating are conducting.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now my personal scientific area of expertise let's say is what's known as the terahertz region of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And here in this figure what i'm showing is the electromagnetic spectrum are different kinds of different colors of light separated by their different frequencies.

Ben Ofori-Okai: As I mentioned before, and as as a whole and, as you might know that light is an electromagnetic wave because it's a wave, it has a wavelength, and it has a frequency and different colors are basically described by different they're different frequencies.

Ben Ofori-Okai: What makes terahertz radiation or terahertz light particularly useful for understanding the electrical conductivity is that it sort of just pushes electrons slowly through the material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And this gives the electrons enough time to sort of be pushed and be moved and so, in that way.

Ben Ofori-Okai: You can measure you can get a really good sense of how many free electrons you have and by consequence of develop a good picture for how conductive the material is.

Ben Ofori-Okai: This is in comparison to other higher frequency radiation like through the visible ultraviolet and X rays.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Where the the light actually could push the electron so quickly that the electrons can't move and and that actually creates transparency for some kinds of light and even higher frequencies.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So, given this, then how might one use terahertz radiation in an experiment to measure the electrical conductivity.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Well, so here's an example. Ben Ofori-Okai: So if you take terahertz radiation and you send it through air and then this plot what i'm showing as a measurement of a terahertz signal, so this is a measurement actually of the wave like behavior.

Ben Ofori-Okai: of electromagnetic radiation at terahertz frequencies, and you can see that it has a peek it has a valley, just like you'd expect a wave to have.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And if you send a terahertz pulse through air, you see, you can record it signal and what you'll see is that you have some signal right and that just tells you how much light that you have.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And in this case because we expect air to be an insulating material we get a lot of light through in our measurement.

Ben Ofori-Okai: If we compare that to what happens if, instead of trying to send tear her a terahertz pulse through air you instead try and send it through a piece of aluminum which we know to be a good conductor.

Ben Ofori-Okai: What you'll see if you look at your screen, maybe you can't see it if you're looking at your screen, is a very, very, very, very weak signal.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Right, it might just look like a flatline maybe you have a giant screen at home, and you can blow it up and take a look.

Ben Ofori-Okai: i'll try and make that a little bit easier for you and magnify that signal by about 40 times.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so here, you can again see the oscillation of the wave that's characteristic of it being light, but it's much, much, much reduced in how big the signal is.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And again, this is what we would expect for something that's conductive because light doesn't want to penetrate or doesn't want to move through through a metal.

Ben Ofori-Okai: and Ben Ofori-Okai: We can actually use this as a way of extracting what the material conductivity is.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And we can do, one more interesting thing, actually, which is that we can take a very, very, very high energy or high intensity laser pulse, and we can use it to heat up the aluminum very, very quickly.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And in this case, then, if you pass the terahertz pulse through this material what you see is a very is a dramatic increase in the amount of light that's transmitted.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And in this case, the increase in the terahertz signal means that there's a decrease in the electrical conductivity.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And this is kind of interesting on its own, because it means that when you take a material and you heat it up a lot, and you take this metal and you heat it up a lot.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The conductivity that you actually determine is different from what it was at room temperature.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And normally when you think about heating things up you think about them moving faster, so you might think Oh, the electrons will move faster we have a higher conductivity, but in fact we don't we see that we have a lower conductivity.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And this is also important because there are a lot of different theoretical models for how to calculate what these kind of activities could be.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And this sort of data can be used to verify whether or not certain models are right or wrong and validate different kinds of theories which can help scientists predict conductivity is of other materials.

Ben Ofori-Okai: OK, so now getting back to what we're going to try, with the sort of experiment that we would hope to do.

Ben Ofori-Okai: we've talked about how we can measure the conductivity we've talked about how we can.

Ben Ofori-Okai: drive materials to high temperature and high pressure and so Now the question is, how can we sort of combine all of these things and get to the conditions that we want to at the Center of the earth.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And also, how are we going to know what conditions we've gotten to how are we going to know whether or not the materials, a solid or liquid, so that we know what part of a space that we're in.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And this, it turns out, can be done using my second favorite part of the electromagnetic spectrum X rays.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Thanks to the scientific father and son to have William and Lawrence Bragg what they discovered was that if you take X rays, and you shine them on to a crystal or onto a material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The X rays will diffract and how they do factor, where you start to see an infraction I should say what the diffraction does is it produces an interference pattern that you can measure.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And, based on the spacing of lines or spacing of points in that interference pattern.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Well, you can do is you can actually measure the distance between layers of atoms in the material so that's one thing that you can do.

Ben Ofori-Okai: but also because of that, because it measures, the the the distance between different items as the atoms move and change and they change structure what you'll see is a difference in your diffraction pattern.

Ben Ofori-Okai: What that looks like is sort of illustrated here and i'm showing to sort of simple examples, one being a crystal and solid where what you see as a bunch of different sharp peaks.

Ben Ofori-Okai: This arises because in a crystal you have a very well defined position for all of the items in the lattice and that gives rise to very sharp lines in your interference pattern.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And in that, and then, when the material melts it becomes a liquid the items aren't necessarily in fits positions anymore.

Ben Ofori-Okai: they're sort of roaming around there's some sort of short range order and by consequence you get a broadening of this line, or you see you know one or maybe two primary features in your X Ray diffraction.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, this lets you see very, very clearly the difference between a solid and liquid, and this will allow us to then figure out whether or not we're in the solid phase, or the liquid phase of, say, iron or nickel or any other material that's out the earth's core.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So, putting it all together, then we need high energy lasers, we need X rays, and where are we going to find all of these things well, it turns out that the answer is right here at SLAC at the Linac coherent light source.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The Linac coherent light source, the world's first a hard X Ray free electron laser and what that means is that it can produce these very, very, very short bursts of light.

Ben Ofori-Okai: At X Ray frequencies, and this is perfect for trying to make measurements of these very, very, very short lived states of the material that we drive our samples to in a dynamic compression experiment, or in the laser driven compression experiment.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And all of these things will coalesce in one particular end station, called the matter and extreme conditions end station.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And here this photo shows, one of the large experimental Chamber that we have at the matter and extreme conditions and station.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Where the lasers that are using these experiments create extreme states of matter that are found not only at the course of planets but also in other astrophysical objects.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so we sort of think about it as being able to look at the universe in this recreate different parts of the universe in this giant chamber.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Now what the experiments itself that one would need to do for measuring the conductivity would look like it's something like this.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So you'd start off with a sample you'd start off with that a bit later that I told you about before and then, in this case, we also add a window like a thin window and that window is designed to hold the sample at pressure as the shock wave moves through it.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so we have our high energy nanosecond Dr laser which launches the shock wave into the material changing the pressure and the temperature and the density.

Ben Ofori-Okai: We have our velocity symmetry probe our Vice our pro for telling us what the shock speed is so that we know what conditions we've gotten to.

Ben Ofori-Okai: We have our terahertz pulse, which is going to measure the reflectivity in this case and, just like we did for the transmission, you can relate the reflectivity to how conductive the material is.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And then, finally, we add X rays, to the experiment which are going to tell us about whether or not the materials in the solid or liquid phase and what its densely might be.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And this is, you know pretty simple looking experiment as i've laid it out here the reality of the situation is, of course, considerably more complicated.

Ben Ofori-Okai: These photos were taken from an experiment that we did a little over a year ago now, setting up for the sort of first trial run of this kind of experiments at SLAC.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Where all of these big sort of metallic looking things are mirrors or lenses designed for driving and in delivering the laser.

Ben Ofori-Okai: To the spot, where we want to look at our sample of interest, of course, for it turns out that a scientist another one of scientists.

Ben Ofori-Okai: best friends besides duct tape is aluminum foil which we have to wrap everything in, and all this for the goal of trying to understand and trying to measure the conductivity in an incredibly small piece of material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So, as I said, we did try an experiment, about a year and a half ago to try and look at.

Ben Ofori-Okai: conductivity changes in that cases it was aluminum. Ben Ofori-Okai: But I can answer sort of the question of like okay well from based on an experiment sort of where do we stand now and what do we need to do in order to reach the earth's core conditions that are of interest.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So now using the current laser that currently their energy that we have at the matter extreme conditions and station.

Ben Ofori-Okai: We were able to get in the configuration for our experiment, we were able to get to you know, three quarters of a of a million atmospheres still a ton of pressure, but not quite enough pressure to get to the conditions that we're interested in.

Ben Ofori-Okai: If we are in, and while this is sort of a shame, we can actually reach you know some of these conditions if we only quadruple the laser energy.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Which in that case would exceed 2 million atmospheres and put us within hopefully within where we expect to be for the years and these earth's core conditions.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And quadrupling the energy might sound like a lot, but the truth is that Thankfully we actually have an exciting upgrade that's planned for the matter extreme conditions end station that will hopefully come online in a couple of years and make these experiments possible.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, even with that right, you know one even once that measurement is able to be done, the question is well what else would you do, what else could you do, what else might be interesting, and it turns out that one of the other planets that is interesting is Neptune.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Neptune is interesting for a couple of reasons really quickly, what I want to say is that, compared to the earth Neptune is full of a whole bunch of different gases.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Right and, unlike the end and these gases aren't necessarily conductive at you know standard conditions and somehow, though.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The conditions on Neptune are such that you that we believe that there's a conductive fluid that's generating a magnetic field.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And not only that the magnetic field actually is a very different structure than the one that we have for earth.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So in this figure that's right above me these red regions would basically indicate that if you put a compass down, it would point north.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Where and the blue regions indicate that the compass would point South and what we can see is that it doesn't it actually like like you know way that is different from how it is on earth.

Ben Ofori-Okai: where you are with your compass will point in a very, very different direction, and so this means that, overall, the structure that.

Ben Ofori-Okai: We believe the structure of neptune's magnetic field is very, very different and so that again opens the question of why what's changing what's different between these two between these two our planet and Neptune that makes the this this happen.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And lastly, just a couple of years ago there was an exciting Nobel prize that was given out for the discovery of what are called exoplanets.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And exoplanets are planets that are outside of our solar system but inside, you know within our could be within our galaxy.

Ben Ofori-Okai: That have various different sizes and compositions and also in some of these cases, we expect them to have magnetic fields.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But they're also made up of different kinds of materials that again because of their their.

Ben Ofori-Okai: sizes and their compositions will be experienced very, very different ranges of pressures, and so one of the questions, then that's a relevance is whether or not these materials would exhibit magnetic fields or should exhibit magnetic fields, based on the conditions that we estimate.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Their their constituents to the the conditions we expect their constituents to experience.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, even when the earth's magnetic field question is solved, there's a lot of other interesting science that can be done a lot of interesting physics that can be learned.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And i'm hopeful that over the next couple of years i'll be able to tell you more about some of that science as as we conduct more measurements and as we learn more and understand this better.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so, with that i've reached the end of my talk, I think that i'd like to take this opportunity again to thank you for signing in.

Ben Ofori-Okai: and also to thank the many, many, many people that i've had the pleasure of working with over my time at slack.

Ben Ofori-Okai: there's definitely should be a saying that no scientist is an island, these are these intensely collaborative experiments that require people from all over the planet.

Ben Ofori-Okai: tuning in dialing in giving their expertise, giving their feedback, in order to make these experiments possible and I definitely wouldn't be able to do them by myself and in the process we sometimes get to have fun doing what we're doing and learning what we're learning.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Be it either in person, as we were able to do years ago over zoom as we sometimes have to do now.

Ben Ofori-Okai: These are, these are these are can be really fun and rewarding experiences and in large part because of the people that I get to work with.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So it also like to make sure, to thank the Department of Energy fusion energy sciences, which is our main funding source the SLAC national accelerator lab for awarding me the Panofsky fellowship recently.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And then i'll leave this slide As my final slide and again, thank you all for your attention, thank you for tuning in I hope that you.

Ben Ofori-Okai: enjoyed something learn something had some fun with this and, at the moment i'm going to take the opportunity to also introduce the panelists who will be helping me with a question and answer session Emma McBride and live fletcher.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Emma mcbride is herself a panofsky fellow Luke is a scientist within the HED within the HED group and i've had the immense pleasure of working with the two of them learning from them, since I joined SLAC.

Ben Ofori-Okai: there's definitely no greater pair of people that I think i'd have I would work with our i've enjoyed working with over the last five years, and so I appreciate them taking their time to.

Ben Ofori-Okai: help me answer the questions that you field so again, thank you and I will be back shortly for the question and answer session.

michael peskin: Okay, well then, thank you very much. michael peskin: This is pretty fascinating stuff.

michael peskin: um. michael peskin: When you're ready, we can begin to ask the questions.

michael peskin: There you are okay. michael peskin: So.

michael peskin: Let me start out with some kind of more basic things. michael peskin: um Ann would like to know.

michael peskin: You said Bragg diffraction can detect the difference between a crystal and solid versus a liquid.

michael peskin: So is the metal in the core of the earth Crystal and at any appreciable scale and maybe I should also ask this is under millions of atmospheres of pressure, are these crystals weird or are they just like the crystals that you have an ordinary metals.

Ben Ofori-Okai: I think I can I can hazard a guess, but I do think that either Emma or Luke might have might have more experience and have a better answer to this sort of question so if either of you want to start with it.

Ben Ofori-Okai: That would be appreciated I guess. Emma McBride (she/her): Oh Ben I would have volunteered to start with it, but after that picture you showed us some final slide i'm not so sure, but it was a wonderful talk.

Emma McBride (she/her): really excellent excellent work, so I mean my answer would be that the core the inner core of the Earth is a solid, so it is crystal and and we expect that to be in the hexagonal crystal structure but it's this this outer core of the earth that you mentioned, is a liquid.

Emma McBride (she/her): What I think is pretty interesting and maybe scary on a billions of billions of years perspective is that the the inner core is growing.

Emma McBride (she/her): And it's it's eating away at the outer core and transforming the liquid there into a solid so maybe you then Ben can comment on what that means for for the magnetic field.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Why do you think I do as I, as I understand it, and there's there's a lot of evidence for the reduction in the strength of the earth's magnetic field over time.

Ben Ofori-Okai: At this point, it's a little hard to say how much of that is going to be due to the fact that there's less conductive material.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Around the outer core or in the outer core versus whether or not we might be approaching one of these geomagnetic reversals where the field.

Ben Ofori-Okai: flips in polarity and so maybe it just goes to zero, at some point, whatever that means or whatever, that would be like that could be really terrifying because we might not get the northern lights for a couple thousand years or however long that process would take.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But yeah I think that I think that that would definitely I mean, I also believe that.

Ben Ofori-Okai: For Mars, there is an idea that at one point, its core might have been liquid, and so it might have had a magnetic field.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But then, as the core sort of froze out the magnetic field eventually just disappeared.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But yeah that is that's definitely a thing that is worth considering and worth being mindful of and hope and I and yeah that's all i'm going to say about that.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So I don't know if Luke has any comments or any other thoughts to bring to the party.

Luke Fletcher: No, I think both of you answer it. michael peskin: um Abby would like to know how do you know that the material subjected to these high pressures and temperatures in your experiment which lasts only for a nanosecond.

michael peskin: actually make a material that behave, similarly to what's in the earth's core, which has been in that condition for billions of years.

michael peskin: So why is one a good model for the other.

Ben Ofori-Okai: I have, I have what I hope is an answer. Ben Ofori-Okai: and, and that is is that so that's one that's a great question it's a question that I think we get often in terms of how we.

Ben Ofori-Okai: can understand the physics that we're doing and how it relates to these incredibly long, long time scales.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And the the sort of the short of the answer that I the the way that I like to think about it. Ben Ofori-Okai: Is that it's true that, yes, the the core of the Earth is this thing that's evolved over billions of years right.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But how charges let's say we'll move inside the core of the Earth is this sort of steady state is this is this it's a dynamical process, but if you're sort of wondering about how it behaves on average.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And how it behaves on average is a thing that you can learn even from a material that sort of living for a sort of a relatively short amount of time, depending on how you choose to make the measurement so again it's, not to say that we necessarily need to make.

Ben Ofori-Okai: This material and let it sit around for a really long time to understand how it behaves.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Just knowing that Okay, if you try to apply this much forced to move this many electrons over the over a timescale that's long with respect to how long it takes the electrons to move.

Ben Ofori-Okai: that's going to give you a lot of information on how these materials behave and that's that's sort of how I think about I don't know if either of you, if you want to add anything to that or if there's anything that you might might change about what i've said.

michael peskin: Anyone. Luke Fletcher: Know hey you're talking to the panel. Ben Ofori-Okai: yeah to the panel ya.

Luke Fletcher: no, I think I think it's a incredibly astute question actually, and this is something that we.

Luke Fletcher: We think about a lot in the field and, in fact, a lot of research done by Emma has has demonstrated that.

Luke Fletcher: These materials will behave differently under a shock than they would, if you just steadily squeezed it and held it at a condition for a period of time.

Luke Fletcher: So even that we're we're learning about, but I think. Luke Fletcher: The connection to astrophysics is still relevant in terms of the kinds of extremes, as you get and where you can sort of approximate how these things are going to behave and they should translate quite well.

michael peskin: yeah, I guess, I should say that it's a measure of how small atoms are I mean a million a millimeter is.

michael peskin: A 10 million atoms. michael peskin: it's amazing so sorry did I get the decimal point around 10 billion atoms, fit in a millimeter so you can be extremely small and ordinary scales and still be huge compared to Atoms and that's part of what makes it work.

michael peskin: Okay um Alyssa would like to know how do we actually know what the magnetic fields are another planets we know what they are on earth, because we have campuses but out there, what knowledge, do we have.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Do either you want to take this? Ben Ofori-Okai: I think I have a suspicion that you might have I mean my my guesses are my understanding is that.

Ben Ofori-Okai: it's from these like these space missions these like these spacecraft probes that admittedly do sample only a fraction of what that magnetic field looks like as it gets some amount of orbit around the planet.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And then the rest of it, I believe, is estimate to made on modeling. Ben Ofori-Okai: Based on what we understand about the console so in a sense, sort of taking what we believe to be the the origin system, which is the dynamo understand basing are including what we think we understand about the compositions of these planets and.

Ben Ofori-Okai: You know the pressures and temperatures, we think that their course or I sort of sticking it into this model and saying okay well.

Ben Ofori-Okai: We know that the magnetic field sort of looks like this, and this model would give us the magnetic this model gives us that magnetic field but there's sort of a lot of input parameters that we need to.

Ben Ofori-Okai: That that sort of needs to go into get like a like a high quality let's say 3D map of what the magnetic field on the surface of one of these planets looks like.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So again, an excellent question a really important question to for validating or for understanding, whether or not we think we know, based on the measurements, that we do, whether or not our models are good or bad.

Emma McBride (she/her): I can just add like it's it's pretty exciting time for looking at the planets in our solar system and outside of it.

Emma McBride (she/her): You know, we have nasa's insight mission to Mars, the bed mentioned knew that there's a lot of information coming out about the interior structure.

Emma McBride (she/her): of other planets from seismic measurements, you know we were stuck stuck on the earth for such a long time and now we're finally going.

Emma McBride (she/her): to other planets and finding out about their interior structure and and the James webb telescope is looking at exoplanets and their composition as well, so the more information we get the better our models get as well.

michael peskin: So Kim has a question but it's really a two part question i'm going to ask it to you in two parts, the first one is why does the magnetic field of the earth mainly align with the geometric North Poles, that is, with the rotation Is this something that's expected in dynamo theory.

michael peskin: And then, part two, is well, what about uranus and Neptune, why does that work but i'd like answers to both parts, if you would.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So, I guess, starting with the first part. Ben Ofori-Okai: I think that the the shape of the magnetic field is supposed to be given by basically how the flute like the shape of the conductive fluid near the Center of the planet.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so the I don't know how much of it is coincidence, because the the let's say the scale of these calculations is actually really, really, really, really massive.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And even the input parameters that they put into these calculations, if you tweak something here or there, you can get very, very different.

Ben Ofori-Okai: values for the field, so I think I think it mostly maybe this is sort of answering both parts of the same time.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But I think it basically depends on whether or not let's say the Center of your your conductive fluid is a ball versus a Shell and where that Shell is with respect to the Center or ball slash shell where that is, with respect to the Center of the planet.

Ben Ofori-Okai: that's my understanding, anyway, and unless and I don't know if you guys have any other, either of you has any other.

Ben Ofori-Okai: thoughts or maybe better understanding that I do.

Luke Fletcher: Now, I think the structure of the planet in terms of the core and the mantle is is the most important part, and what would dictate where the fields go.

Luke Fletcher: In terms of looking different I think if you lived on Neptune you might look at earth as being a strange magnetic field, so I guess it's all relative.

michael peskin: i'm going to do we know what the core of uranus and Neptune look like, is it similar to the earth or it's really different.

Luke Fletcher: that's a good question that's something that we're we're still learning about.

Luke Fletcher: The solid hybrid experiment. Luke Fletcher: But a lot of experiments that we're doing right now we're looking to investigate.

Luke Fletcher: What these cores are made of. Luke Fletcher: By reaching these conditions and seeing if they.

Luke Fletcher: would conduct, for example, of hydrogen if you were to take that and compress it would you reach a metal metallic state, and this would be a perfect sort of core to create a dynamo.

michael peskin: interesting. michael peskin: um. michael peskin: The.

michael peskin: you're just excuse me. michael peskin: So Marta has the following question kind of a silly question, but why is the terahertz range on the electromagnetic spectrum, the only one, I haven't heard of before.

michael peskin: They seem very useful for your work, but I guess they aren't very useful for everyday things like radio waves microwaves UV etc.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So this is also a really good question um so so there's a lot I guess there's a lot of different ways, I can answer this.

Ben Ofori-Okai: I think one important part of why.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Why, I mean in some senses it's sort of like Why is terahertz hard like Why is terahertz radiation, or maybe maybe to back it up the better way to say this is.

Ben Ofori-Okai: The reason that you probably haven't heard of it is because terahertz radiation actually happens to be surprisingly hard to make and surprisingly hard to measure.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And sort of the reason for that you can think about as coming from if you wanted to make lower frequencies so like radio waves microwaves.

Ben Ofori-Okai: That sort of kind of radiation, you can do it by sort of mechanically moving a thing like mechanically moving an object and as that object mechanically moves it would generate radiation and for lower frequencies, you can move that object slowly and you'll get radiation out.

Ben Ofori-Okai: But as you try and turn it faster and faster what you find is that there's a fall off in the efficiency for sources that are based on this sort of technology that sort of dies in the terahertz region.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And from the other side of it, the same sort of physics that's responsible for admission from like a light bulb or from a laser which involves electrons within an atom being given a lot of energy and then releasing that energy again.

Ben Ofori-Okai: That that that sort of loses efficiency, also in the terahertz region because the amount of energy that you have to give the amount of extra energy that you have to give.

Ben Ofori-Okai: To the material is not that different, and in some cases even smaller than the amount of energy that you get from just sort of being warm so it's hard to get like extra radiation out of, from a source like that.

Ben Ofori-Okai: And so that's sort of why so so no it's and it's not it's not a silly question, and in fact it's.

Ben Ofori-Okai: A question that the sort of a scientific community sort of sprung into existence about 30 or 40 years ago because we sort of developed.

Ben Ofori-Okai: Some tools, with the development of high energy high intensity lasers that could move charges around very, very quickly, and this is sort of the this sort of gave birth to the terahertz the field of terahertz science and technology.

Ben Ofori-Okai: So that that's sort of a long winded answer to what is not a silly question, so thank you for the question.

michael peskin: A couple people out there have questions about volcanism, of course, we just had this recent volcano in Tonga, which was the big event from the human point of view.

michael peskin: Does volcanism magma molten metal coming out of these things affect the earth's magnetic field is this a contributor to the story or it's just kind of a small phenomenon with respect to what you're talking about.

Ben Ofori-Okai: I don't. Ben Ofori-Okai: know.

Ben Ofori-Okai: I never thought about it. Ben Ofori-Okai: Or, I never and I haven't looked into it, so I don't know if if either of you to have.

Ben Ofori-Okai: have an answer for that.

Emma McBride (she/her): Luke, I don't know if you do, I would say that my instinct is that it's a very much a human problem and that it doesn't greatly affect the magnetic field, but you know i'm fine if you want to completely disagree with me.

Luke Fletcher: So, just to clarify the question we're talking about volcanoes. Luke Fletcher: volcanoes affecting. Luke Fletcher: The magnetic field?

Emma McBride (she/her): convection from the mantle or similar. Luke Fletcher: um, you know I guess I don't know the exact answer that but I just say, based on the the overall scale that we're talking about it would probably have a very small effect of you kind of compare.

Luke Fletcher: The crust of the Earth is just very tiny compared to the overall mantle you know that the processes are happening, the mantle would most likely dominate.

Luke Fletcher: Anything that would happen at the surface. michael peskin: I guess when you read the literature about the effects of volcanoes it's always the kind of black dust that they churn up.

michael peskin: which affects the heating and cooling the earth, much more than the magnetic properties.

michael peskin: You know. michael peskin: um let's take ah one more topic and that's the question of magnetic field reversals.