Christian Tanner wins 2024 SSRL Scientific Development Award

Tanner works on self-assembling nanocrystals, which could be the basis for less expensive, easier to build displays and solar cells.

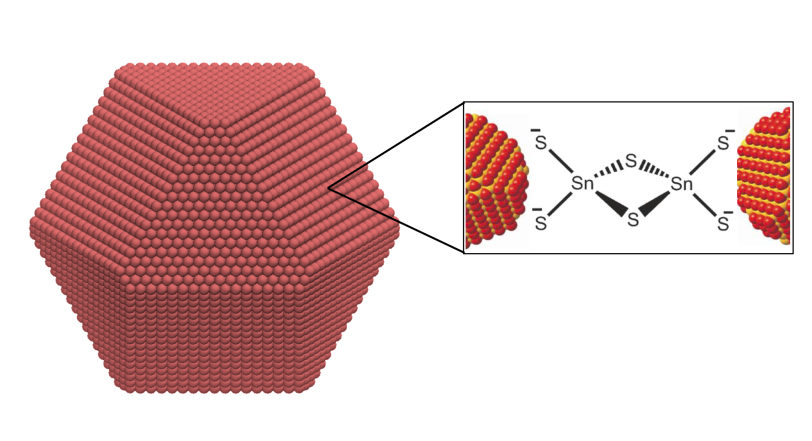

What Christian Tanner wants to do, ultimately, is help create materials that could be applied to building better solar cells or video displays — and to do that big-picture work, he coaxes nanoscopically tiny building blocks to put themselves together and watches the process unfold using X-rays at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

For his efforts, Tanner will receive the 2024 SSRL Scientific Development Award, to be presented at the SSRL/LCLS User’s Meeting taking place September 22-27. The award comes with $1,000 to help promote the dissemination of research performed at SSRL.

“It’s a huge honor, and it’s a privilege to do science at SSRL,” Tanner said, noting that there are many other outstanding young scientists working at SSRL and that his own work is the result of a team effort. “I think that’s something that makes science way more fun.”

Tanner began his research career studying chemistry at Duke University before arriving at the University of California, Berkeley, where he works as a PhD student in the lab of chemist Naomi Ginsberg. There, he studies the self-assembly of nanocrystal superlattices – which is to say, he studies how tiny bits of crystal, just four or five nanometers across, form into larger crystal lattices as they drop out of a liquid solution. These larger lattices follow patterns different from those underlying crystals, creating a hierarchical structure that can be tuned and manipulated to achieve a desired effect.

The draw, Tanner said, is that manufacturers could make materials like solar cells or electronic displays more efficiently and at lower cost – but before anyone can get to that point, researchers need to understand how the superlattices form and how to make larger, more orderly lattices.

“What my research is all about is arranging these crystals in such a way that they have the properties we want,” Tanner said. And, he said, “how they form has huge impacts on the properties of the superlattice and therefore its function.”

To do so, Tanner and his colleagues turn to SSRL’s small-angle X-ray scattering tools. “The reason it’s been so great for us is it lets us see the structure of our nanocrystals in a solution as they assemble,” Tanner said.

Ginsberg highlighted Tanner’s “passion and motivation to work on a most distinctive and risky project, his superlative scientific curiosity and his enabling technical proficiency.” She credited his leadership in “getting a large, multi-institutional project off the ground and seeing it through to bear important scientific fruit, even as a junior grad student,” including developing specialized equipment to inject and mix solutions while in the X-ray beam, new methods for analyzing the data, and key insights into what it means. “I will sorely miss Christian when he graduates. Working with him has been such a pleasure and a truly memorable experience. I have definitely improved as a scientist thanks to him.”

Tanner loves the work. “I’ve always been interested in chemistry and physics and math,” he said. “What excites me about this is it’s so complex and disordered and messy, but somehow we’re able to find the beauty in it and also have it be useful.”

SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.