SLAC-led Energy Frontier Research Center awarded $14.4 million to advance new manufacturing solutions for microelectronics

Funded by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, the Center for Energy Efficient Magnonics brings together a multidisciplinary group of researchers from SLAC and seven universities to discover how components of microelectronics can be built on spin waves that arise from magnetism.

A new Energy Frontier Research Center (EFRC), supported by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and led by SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, was awarded $14.4 million over four years to advance manufacturing of microelectronics by investigating approaches to building their components in fundamentally new ways.

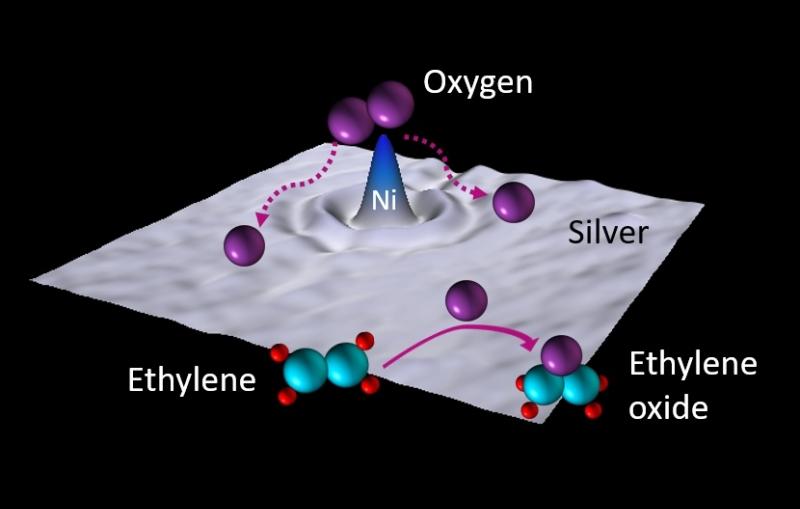

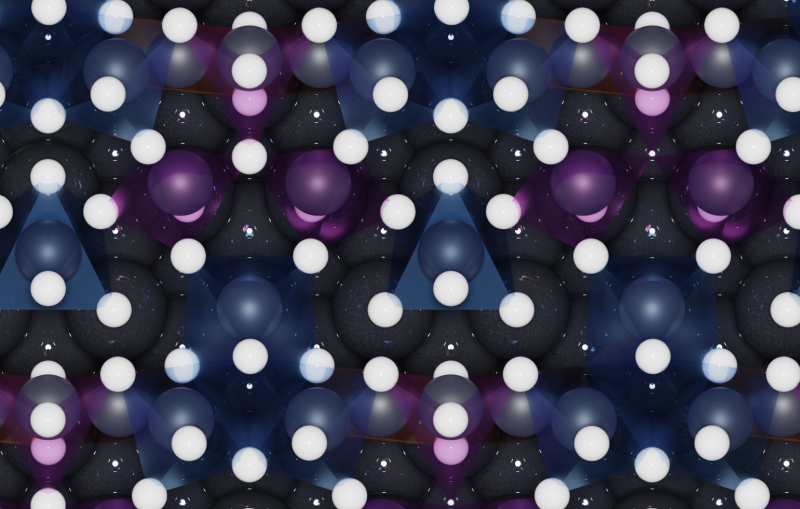

Instead of moving electrons through conducting metallic interconnects in the miniscule and ever shrinking parts of devices such as microchips used in computers and cell phones, the researchers propose to move information via spin waves that can propagate through semiconductors and even insulators. A spin wave is a wave of energy that moves through a substance due to modulation of magnetic moments of atoms.

“Over the years people have tried to manipulate the electrons that produce charge in traditional microelectronics by manipulating their spin, but whenever you move around electrons you have charge current, and when you have charge current you are dissipating energy, which will cause all kinds of heating and resistance,” explained Yuri Suzuki, Stanford professor and principal investigator with the Stanford Institute of Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES), a SLAC-Stanford joint institute.

“Our idea is to try a completely different paradigm – what if we can send information via spin waves without electrons or metals? For example, if we could replace copper interconnects with spin wave interconnects in devices, we aren’t flowing any charge current and are going to save energy.”

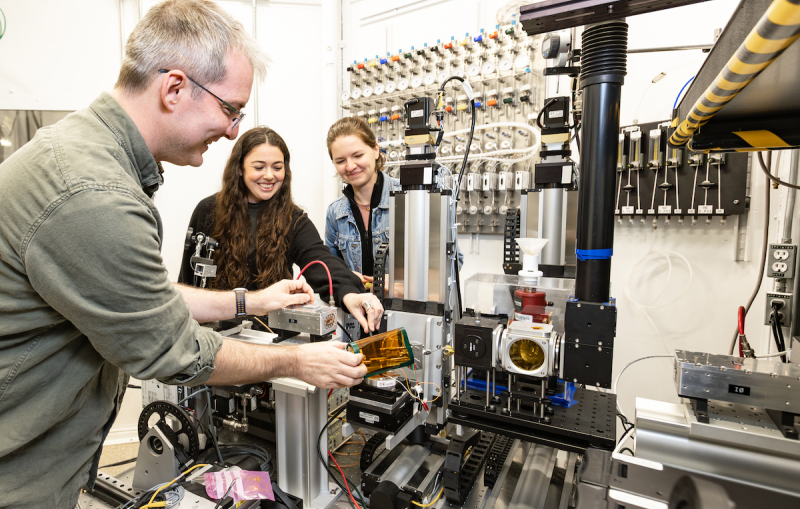

Suzuki will head up the EFRC called the Center for Energy Efficient Magnonics (CEEMag), working closely with SIMES Director Harold Hwang; Wei-Sheng Lee, SIMES lead scientist; and Georgi Dakovski, Matthias Hoffmann and Alexander Reid, lead scientists at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). Other center members include researchers from seven universities – Cornell University; Morgan State University; Northwestern University; Ohio State University; University of California, Irvine; University of Iowa; and the University of Texas at Austin. The multidisciplinary team represents expertise in materials science, X-ray and ultrafast science and electrical engineering, among other areas. The collaboration is taking a co-design approach to advancing discoveries, which tackles all aspects of research and development simultaneously, from basic science to manufacturing.

Access to LCLS, the world’s most powerful X-ray laser, is key, said Suzuki, because to measure and detect spin waves requires timescales and frequencies that LCLS can probe with its ultrafast and intense pulses of X-ray light.

The team aspires to demonstrate the viability of a subset of components in microelectronics based on magnonics, or spin waves, such as interconnects, amplifiers or switches. “We are investigating fundamental science questions to see if technology based on magnonics can move the needle in terms of energy efficiency in microelectronics,” Suzuki said.

Microelectronics, which are increasingly small – tiny fractions of the smallest objects the eyes can see, are essential components in technologies of daily life: communications, transportation, health care, computing, clean energy and more.

The SLAC-led center is one of 10 EFRC’s announced Sept. 4 by the DOE to create world-class teams of scientists for groundbreaking research supporting energy technologies and to bolster the scientific workforce by attracting students to the field of energy science.

“Fundamental research in the areas covered in these awards is critical for generating foundational knowledge that underpins technologies that are important for DOE and the nation,” said Harriet Kung, acting director of the DOE Office of Science. “Strengthening our understanding of the chemistry and materials science behind advanced manufacturing of polymers, microelectronics and quantum technologies will foster a cleaner and more energy-efficient future.”

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.