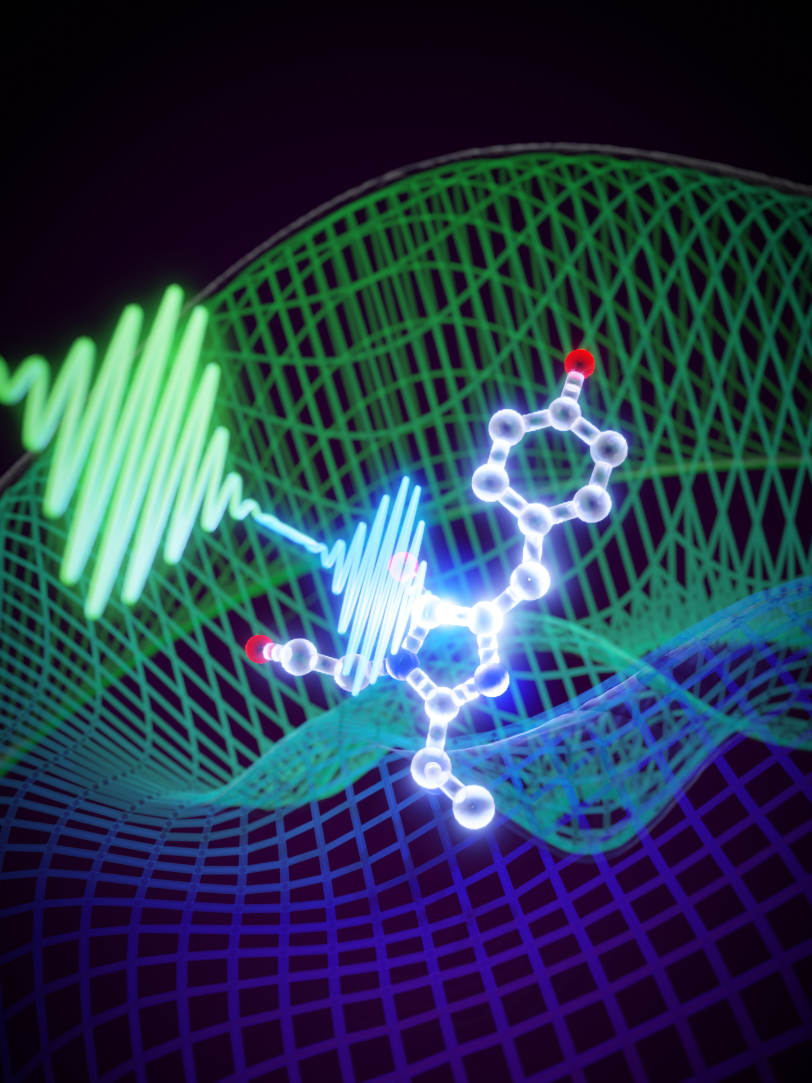

Making molecules dance reveals what drives their first movements

Bringing ultrafast physics to structural biology has revealed the coordinated dance of molecules in unprecedented clarity, which could aid in the design of new light-responsive materials.

How molecules change when they react to stimuli such as light is fundamental in biology, for example during photosynthesis. Scientists have been working to unravel the workings of these changes with several techniques. By combining two of these techniques, researchers have paved the way for new insights into reactions of protein molecules fundamental for life, which could aid in the design of new light-responsive materials.

Previous studies had assumed that all the motions correspond to the biological reaction, meaning its functional motion. But using methods of time-resolved crystallography, which capture changes that happen at different moments, at X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) facilities such as the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), located at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, the team found that this wasn’t the case in their experiments.

The researchers showed that when they excited molecules within a protein, their very first movements are the result of coherence, or synchronized motion. This vibrational effect is unrelated to the light-triggered biological reactions that follow.

These motions are important because they are the natural vibration modes of the molecule, amplified by the laser. They reveal intrinsic and meaningful molecular motion in the ground state, but not the motions involved when the molecule is excited and enters a light-driven process. This distinction, shown experimentally for the first time, highlights how the physics of spectroscopy can bring new insights to the classical crystallography methods of structural biology.

The team, led by Jasper van Thor from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College London, report their results today in Nature Chemistry.

The researchers combined crystallography, a powerful technique in structural biology for taking snapshots of how molecules are arranged, with another technique that maps vibrations in the electronic and nuclear configuration of molecules, called spectroscopy.

In addition to LCLS, the researchers conducted experiments at the SPring-8 Angstrom Compact free electron LAser (SACLA) in Japan, the PAL-XFEL in Korea and recently also the European XFEL in Hamburg.

“These results represent what is truly unique about the capabilities of X-ray lasers,” said SLAC scientist and collaborator Sébastien Boutet. “It demonstrates the type of knowledge of biology in motion that can only be achieved with very short bursts of X-rays combined with cutting-edge laser technology. We see an exciting future of discovery in this area.”

The team was trying to address a key question: What is the origin of the tiny molecular motions on the femtosecond time scale directly after the first laser light pulse?

The researchers excited their sample with an optical laser pulse, and then took snapshots with X-rays. The team created "coherent control," shaping the optical laser pulse to control the protein’s motions in a predictable manner.

They then combined the data from these experiments with theoretical methods in order to apply them to X-ray crystallographic data rather than to spectroscopic data. They concluded that the ultrafast motions do not belong to the biological reaction, but instead to vibrational coherence in the molecules that are left behind after the femtosecond laser pulse has passed.

“Every process that sustains life is carried out by proteins, but understanding how these complex molecules do their jobs depends on learning the arrangement of their atoms – and how this structure changes – as they react,” van Thor said.

“Using methods from spectroscopy, we can now see ultrafast molecular movements that belong to so-called coherence processes directly by solving their crystal structures. We now have the tools to understand, and even control, molecular dynamics on extremely fast time scales at near-atomic resolution.”

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility. This research was supported by the Office of Science.

This article has been adapted from a press release written by Imperial College London.

Citation: Christopher D.M. Hutchison et al., Nature Chemistry, 10 August 2023 (10.1038/s41557-023-01275-1)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.