Researchers adapt a Nobel Prize-winning method to design new, ultra-powerful X-ray systems

Once built, the system could produce fast X-ray pulses ten times more powerful than ever before.

By Kimberly Hickok

If scientists want to push the boundaries of, say, an X-ray laser, they may need to create some new technology. But occasionally there’s no need to reinvent the wheel. Instead, scientists simply come up with a new way to use it.

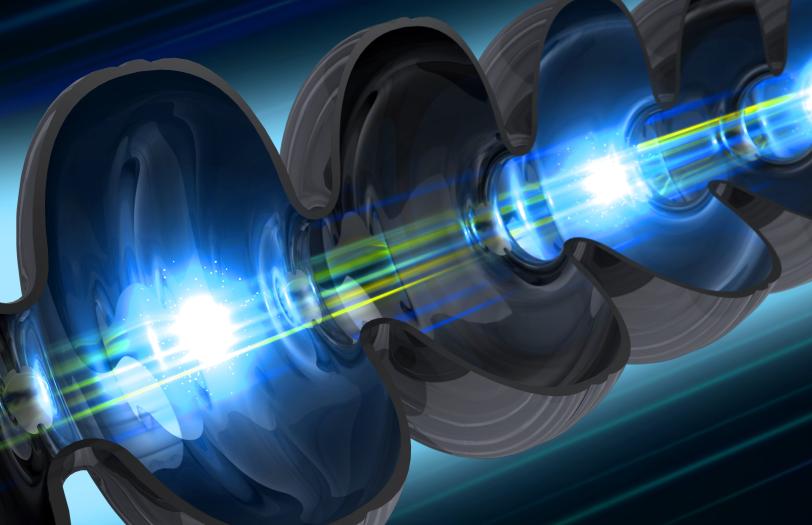

Now, researchers at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have done just that in an effort to push the capabilities of the lab's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL). By adapting a technique for modern, superpowerful optical laser pulses called chirped pulse amplification (CPA), the SLAC team has designed a system capable of producing X-ray pulses ten times more powerful than before – all while staying within the LCLS's existing free-electron laser infrastructure. The team published their results in Physical Review Letters on November 18.

“Current X-ray laser pulses from free-electron lasers have a peak power of roughly 100 gigawatts, and usually with a complex and stochastic structure,” said Haoyuan Li, a postdoctoral scholar at SLAC and Stanford University and lead author of the new study. With chirped pulse amplification for X-rays, “we’ve shown that we can achieve very impactful beam parameters of greater than 1 terawatt peak power and a pulse duration of about 1 femtosecond at the same time.”

Even the best laser has its limits

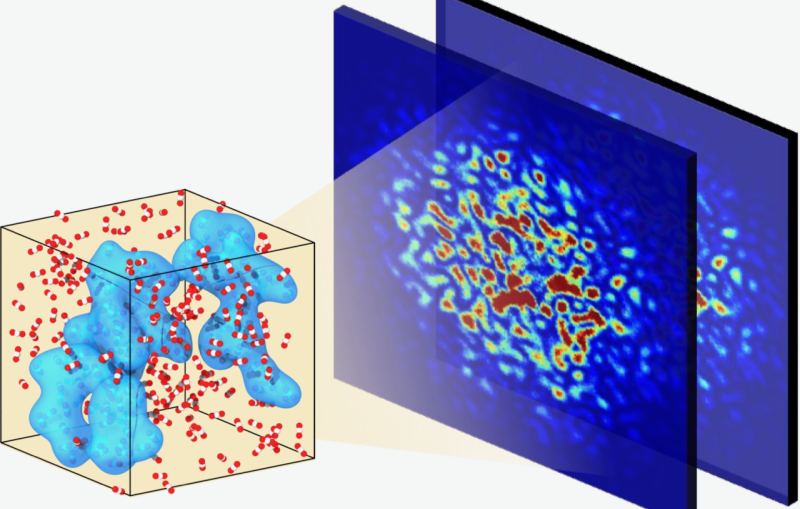

LCLS works like an atomic-resolution camera, taking snapshots of the most minute changes in molecules and materials within a tiny fraction of a second. The ultrabright, ultrafast X-ray pulses it produces are of great interest for many applications and scientific research in fields as diverse as the dynamics of biological molecules, studying astrophysics in the laboratory, and observing how photons interact with matter.

However, increasing the power of the laser can make the timing of the laser pulses inconsistent. That inconsistency creates in turn a distorted or inaccurate image of what’s happening with the system – something scientists desperately want to circumvent. Existing solutions to that problem significantly reduce laser power, limiting what researchers can do.

Because of these restrictions, “in the past decade of XFEL laser experiments, more than 90 percent of experiments used the X-ray source like an ultrafast flashlight,” said Diling Zhu, senior scientist at SLAC and senior coauthor of the study. “Very few really used it as a ‘laser’ in the sense of how we use optical lasers. We are just starting to learn how to manipulate the X-ray beam like we have done for decades with optical lasers.”

Chirping X-rays

CPA was originally designed for increasing the power of optical lasers, and it works by stretching the duration of an energy pulse before it passes through an amplifier and finally a compressor that reverses the stretching done in the first step. The result is a super intense, clean, and ultra-short pulse.

Physicists Donna Strickland and Gérard Mourou from the University of Rochester invented CPA in the 1980s and received the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics for their work. While CPA has revolutionized high energy pulse generation for optical lasers, the technique has proved difficult to adapt for X-ray wavelengths, Li said.

Through designing and implementing crystal optics systems for Angstrom wavelengths, Li and his colleagues learned how X-rays were reflected and dispersed from a crystal in a process called asymmetric Bragg reflection.

“We then realized that asymmetric Bragg reflections can be used to implement the CPA mechanism,” Li said. “Then our X-ray optics team and accelerator physics team worked together to optimize the design based on simulations with realistic beam parameters.”

X-ray pulses within reach

Through detailed numerical modeling, the researchers designed a CPA method for generating high intensity hard X-ray pulses within the beam parameters of existing free-electron lasers. Other designs for such powerful hard X-ray pulses rely on overly optimistic parameters that are out of reach with current technology. “Our new system shows we can produce terawatt, femtosecond hard X-ray pulses with existing free-electron laser facilities,” including LCLS at SLAC, Li said.

The next step is to build the system, which will be a significant engineering effort. "We would like to experimentally demonstrate that we can build the required stretcher and compressor that meet the system design specifications, starting with a miniature prototype,” Li said.

The team hopes to continue their efforts, Zhu said. "Adapting the lessons from many exciting, elegant optical laser technologies to X-ray wavelengths could lead us to brighter X-ray laser sources in the future," he said.

The research was funded by the DOE Office of Science.

Citation: Li et al., Physical Review Letters, 18 November 2022 (10.1103/PhysRevLett.129.213901)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.