Q&A with Stephen Streiffer, the new Stanford VP for SLAC

After decades of experience in the DOE lab system and as director of a leading synchrotron light source, he’s back to where he earned his PhD – with a much bigger mission.

By Glennda Chui

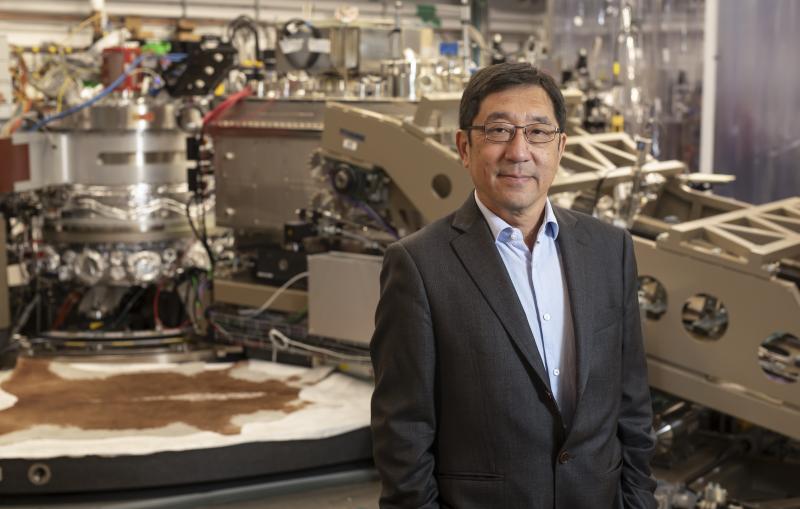

Thirty years after earning his PhD at Stanford University, materials scientist Stephen Streiffer will be back on campus next week – this time with an outsized role to play. As Stanford’s new vice president for the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, he’ll play a key part in advising and supporting the lab as it carries out its scientific mission.

Streiffer comes to Stanford and SLAC after 24 years at Argonne National Laboratory, where he did research at the lab’s Advanced Photon Source, directed APS for eight years and most recently served as chief research officer and deputy lab director for science and technology.

So he’s more than familiar with both the national lab system and the importance of DOE Office of Science user facilities, like APS and SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) and Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), for both fundamental research and experiments with more immediate practical value.

Streiffer got his bachelor’s degree in materials science and engineering from Rice University in 1987 before coming to Stanford for graduate work.

“One of my earliest memories was of the Apollo moon landing,” he said in a profile article published two years ago by the DOE Office of Science. “It really set the imagination free in terms of what science, engineering and technology can do. I was about three years old, so this has been a lifelong passion.” As for his longstanding interest in materials and their nanoscale properties, “I remember, as an undergrad at Rice, sitting on a granite bench, staring down at all the individual rock crystals, wondering about their structure,” he said. “I knew at that point I was hooked.”

What will you be doing as Stanford VP for SLAC?

Stanford University has a contract with DOE for operating SLAC. (It’s even a little more complicated than that, because Stanford owns the land that SLAC sits on.) So it’s a three-way relationship between the lab, the university and DOE.

My job is to ensure that the lab is being managed and operated in accordance with that contract, and to help the lab, particularly the lab director, deliver the things DOE needs to carry out its scientific mission.

One of the great things about working at a national lab, in my view, is that everybody is working on the scientific mission. The scientists are working on the mission, people in HR are working on the mission – everyone is working together to deliver the science and technology solutions that the nation needs in everything from clean energy to fundamental science.

To do that, the lab has to deliver on its infrastructure and operational missions as well. It all needs to come together.

You started out at Stanford; what did you do there?

I was in John Bravman’s group in the Materials Science and Engineering Department, which did a lot of work at SSRL on things like trying to understand how the metal wires on semiconductors behave during manufacturing. I never actually did an experiment at SSRL, but I had a lot of colleagues who did, and in fact there’s a figure in my dissertation that comes from SSRL experiments.

SLAC is the only U.S. lab with two X-ray light source facilities – SSRL, one of the first big light sources to open to users back in the mid-80s, and LCLS, the first hard X-ray free-electron laser, which opened 13 years ago. As a light source guy, can you talk about why these types of big national user facilities are important?

In many ways, light sources are the crown jewels of the DOE complex, and LCLS is the crown jewel of the crown jewels. Very similarly, SSRL offers opportunities to do world-leading science using a different set of techniques. They complement each other. It’s a great pleasure to be associated with a laboratory that has both a storage ring light source and a free-electron laser, because what they do is so different – you can’t replace one with the other.

The research we can do at these light sources falls into two categories.

First there’s fundamental work that really changes what we think about the world by looking at everything from the way that chemical reactions occur and electrons move in molecules to the way that materials hold together in structural alloys for the automotive and aerospace industries.

In addition to that, there’s the more use-inspired applied work where the ability of X-rays to penetrate into things allows us to look at active processes or engineered systems to understand how they work in a way that’s unique. Early work that was done at SSRL, looking at how compound semiconductors grow, is a good example.

The national lab system is really good at operating these types of facilities. For instance, at SLAC and Stanford we have cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) facilities, which have great applications in life sciences for problems that just can’t be addressed otherwise, like being able to look at protein structures and the way that cells behave.

How do you see the relationship between SLAC and Stanford?

One thing that’s really exciting to me about this job is the degree to which Stanford and SLAC are in synergy and can help each other. So, I very much look forward to being in a position to help further relationships between the university and the lab.

There are a lot of these ties, and I think SLAC and Stanford do a great job. But there are all sorts of new opportunities, too, for example with the new Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability – the university’s first new school in 70 years. It presents a wonderful opportunity to link up the DOE’s mission in clean energy with the school’s broader vision of sustainability, and to find ways we can work together on these challenges.

SLAC and Stanford also work together on new classes of quantum sensors that give you unparalleled ways to make probes for exotic phenomena like dark matter. They’re both founding partners of the DOE’s Q-NEXT initiative, and they are building and outfitting one of the two foundries that will make high-precision superconducting devices to support the initiative’s work in quantum sensing, quantum communication and quantum storage.

Another big area of collaboration is through the four SLAC/Stanford joint research centers, which focus on materials and energy science, catalysis, ultrafast science and cosmology and astrophysics. These collaborations include searching for signals in the first visible light from the Big Bang, lying in wait for dark matter particles from a cavern a mile deep and building the world’s largest digital camera for ground-based astronomy, which will be installed at the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile.

The university and the lab are really complementary and we are going to do great things together. It’s really exciting to come back.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.