Experiments confirm a quantum material’s unique response to circularly polarized laser light

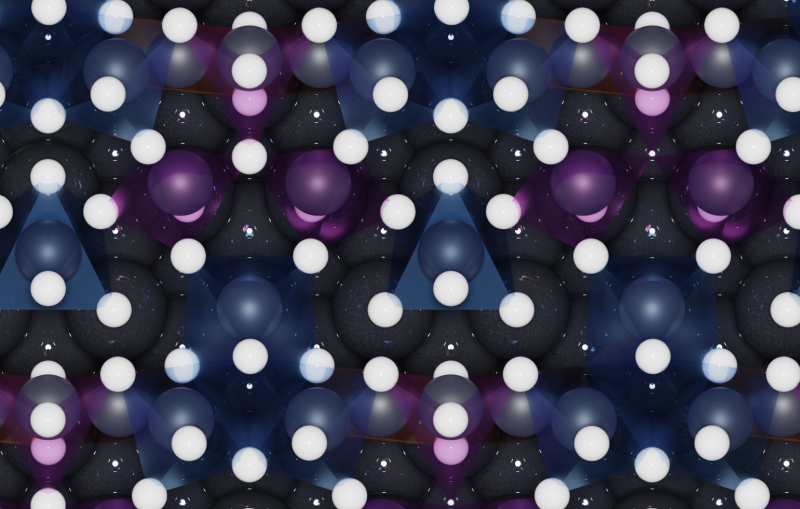

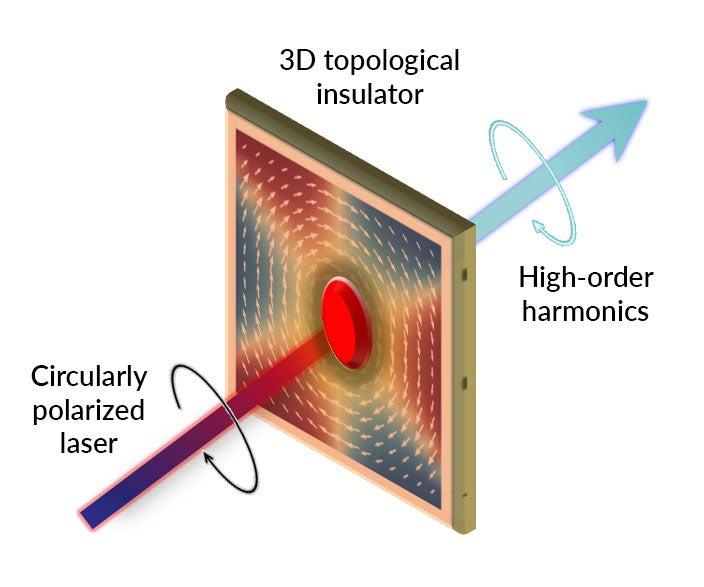

Topological insulators conduct electricity on their surfaces but not through their interiors. SLAC scientists discovered that high harmonic generation produces a unique signature from the topological surface.

By Glennda Chui

When the COVID-19 pandemic shut down experiments at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory early last year, Shambhu Ghimire's research group was forced to find another way to study an intriguing research target: quantum materials known as topological insulators, or TIs, which conduct electric current on their surfaces but not through their interiors.

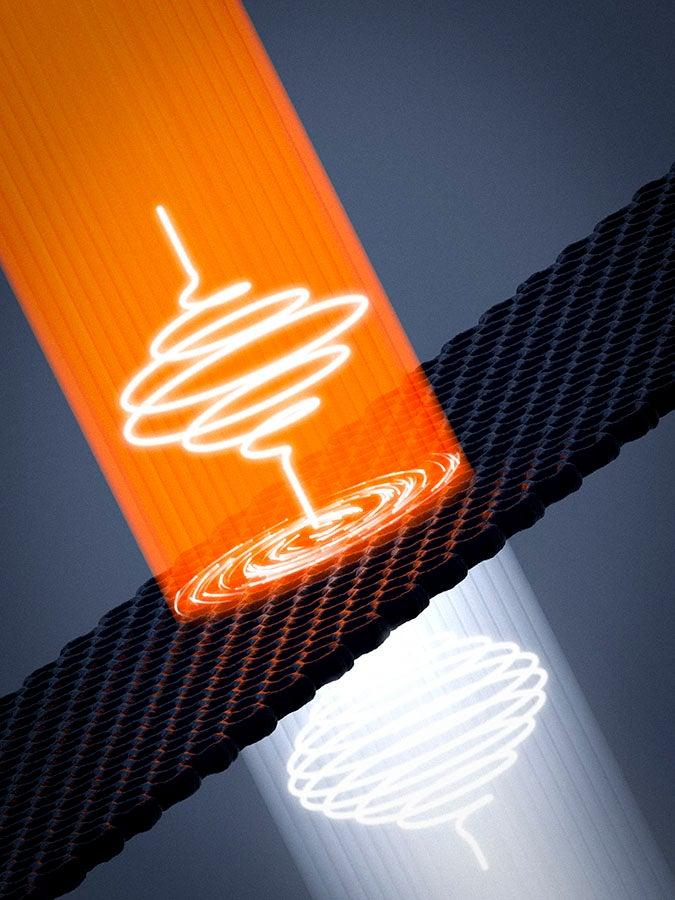

Denitsa Baykusheva, a Swiss National Science Foundation Fellow, had joined his group at the Stanford PULSE Institute two years earlier with the goal of finding a way to generate high harmonic generation, or HHG, in these materials as a tool for probing their behavior. In HHG, laser light shining through a material shifts to higher energies and higher frequencies, called harmonics, much like pressing on a guitar string produces higher notes. If this could be done in TIs, which are promising building blocks for technologies like spintronics, quantum sensing and quantum computing, it would give scientists a new tool for investigating these and other quantum materials.

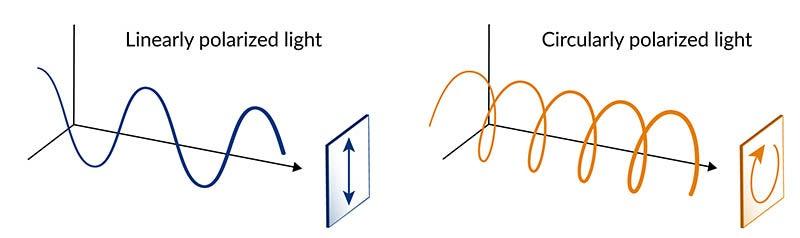

With the experiment shut down midway, she and her colleagues turned to theory and computer simulations to come up with a new recipe for generating HHG in topological insulators. The results suggested that circularly polarized light, which spirals along the direction of the laser beam, would produce clear, unique signals from both the conductive surfaces and the interior of the TI they were studying, bismuth selenide – and would in fact enhance the signal coming from the surfaces.

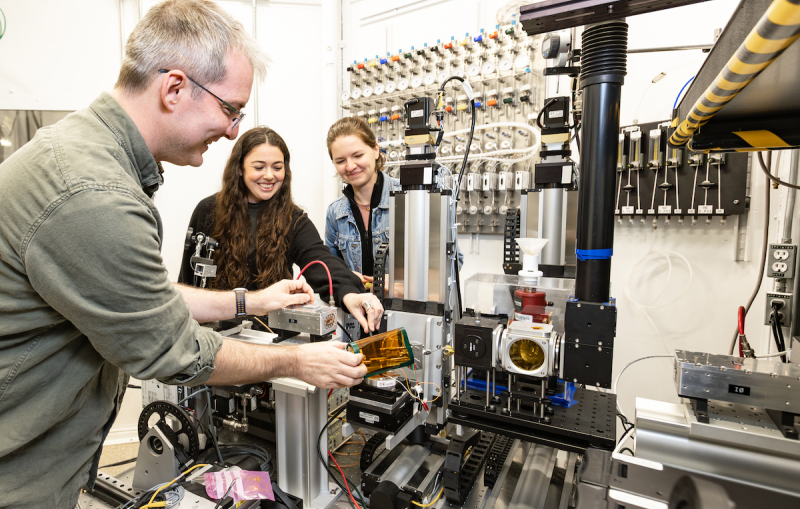

When the lab reopened for experiments with covid safety precautions in place, Baykusheva set out to test that recipe for the first time. In a paper published today in Nano Letters, the research team reported that those tests went exactly as predicted, producing the first unique signature from the topological surface.

“This material looks very different than any other material we’ve tried,” said Ghimire, who is a principal investigator at PULSE. “It’s really exciting being able to find a new class of materials that has a very different optical response than anything else.”

Over the past dozen years, Ghimire had done a series of experiments with PULSE Director David Reis showing that HHG can be produced in ways that were previously thought unlikely or even impossible: by beaming laser light into a crystal, a frozen argon gas or an atomically thin semiconductor material. Another study described how to use HHG to generate attosecond laser pulses, which can be used to observe and control the movements of electrons, by shining a laser through ordinary glass.

But quantum materials had steadfastly resisted being analyzed this way, and the split personalities of topological insulators presented a particular problem.

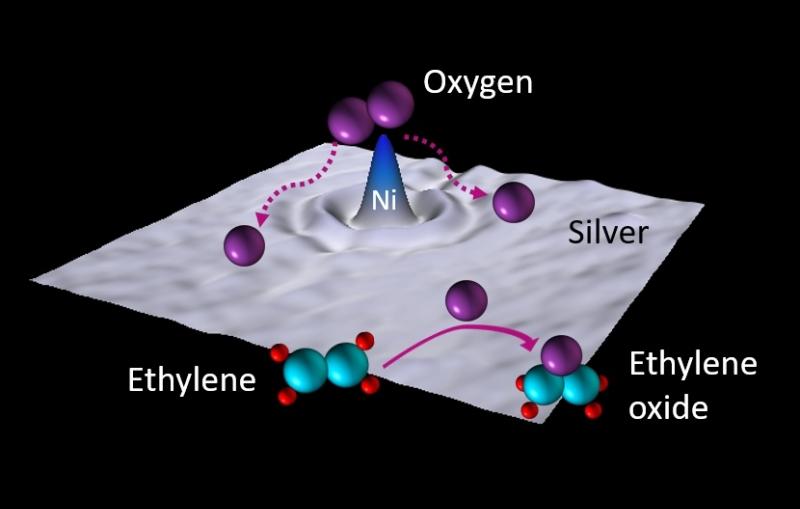

“When we shine laser light on a TI, both the surface and the interior produce harmonics. The challenge is to separate them,” Ghimire said.

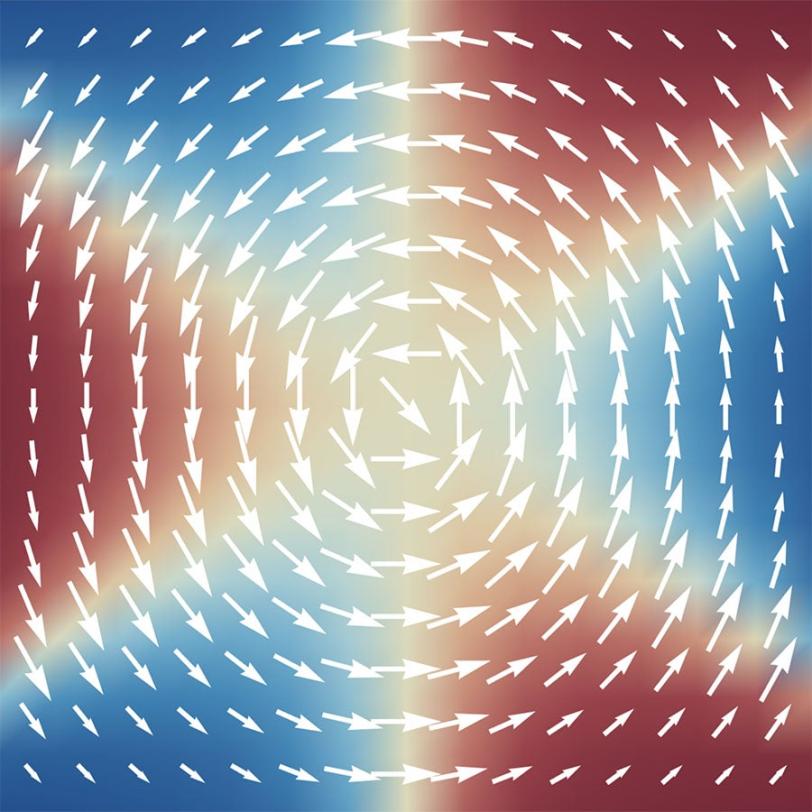

The team’s key discovery, he explained, was that circularly polarized light interacts with the surface and the interior in profoundly different ways that boost high harmonic generation coming from the surface and also give it a distinctive signature. Those interactions, in turn, are shaped by two fundamental differences between the surface and the interior: the degree to which their electron spins are polarized – oriented in a clockwise or counterclockwise direction, for instance – and the types of symmetry found in their atomic lattices.

Since the group published their recipe for achieving HHG in TIs earlier this year, two other research groups in Germany and China have reported creating HHG in a topological insulator, Ghimire said. But both of those experiments were with linearly polarized light, so they did not see the enhanced signal generated by circularly polarized light. That signal, he said, is a unique feature of topological surface states.

Because intense laser light can turn electrons in a material into a soup of electrons – a plasma – the team had to find a way to shift the wavelength of their high-powered titanium sapphire laser so it was 10 times longer, and thus 10 times less energetic. They also used very short laser pulses to minimize damage to the sample, which had the added advantage of allowing them to capture the material’s behavior with the equivalent of a shutter speed of millionths of a billionth of a second.

“The advantage of using HHG is that it’s an ultrafast probe,” Ghimire said. “Now that we’ve identified this novel approach to probing the topological surface states, we can use it to study other interesting materials, including topological states induced by strong lasers or by chemical means.”

Researchers from the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC, the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH) in Korea contributed to this work. Major funding came from the DOE Office of Science, including an Early Career Research Program award to Shambhu Ghimire, and from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Citation: Denitsa Baykusheva, Nano Letters, 22 October 2021 (10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c02145)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.