Case van Genuchten wins 2020 Farrel W. Lytle Award for drinking water treatment research

The honor recognizes his research on technologies for removing toxic chemicals from water.

By Niba Audrey Nirmal

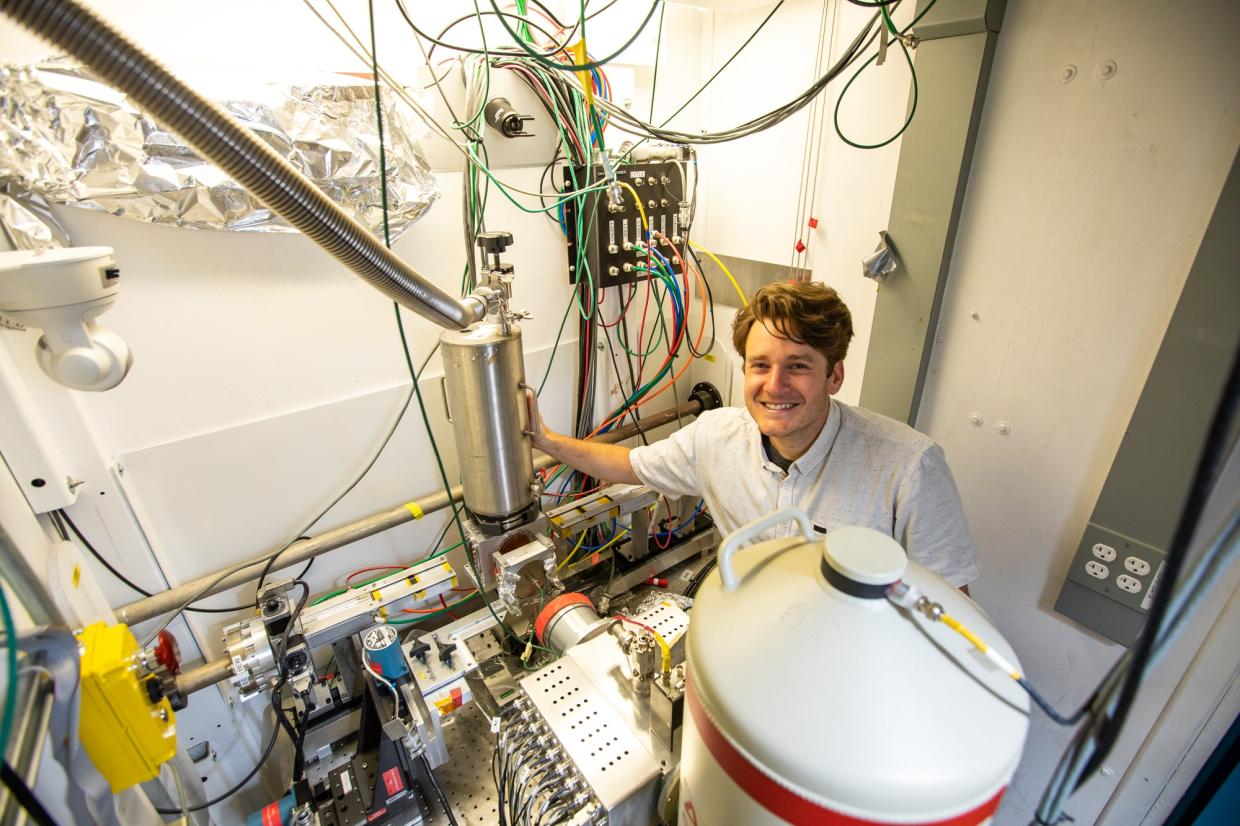

Case van Genuchten, researcher of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland and longtime user of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at DOE’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, won the 2020 Farrel W. Lytle Award for designing technologies to remove toxic chemicals from groundwater.

“This award validates my approach of applying molecular scale techniques to study drinking water treatment problems, which I started 10 years ago as a PhD student,” van Genuchten said.

Launched in 1998, the award has been given to 23 scientists from around the world. Nominees are evaluated based on their contributions and accomplishments in using synchrotron radiation-based science.

“When I found out about the award, I went down memory lane and reflected on the evolution of my career as a scientist and my first memories of coming to SSRL,” van Genuchten recalled. “I was overwhelmed – there are gadgets and gizmos everywhere! And if you've never really been there, you don't know what all these things do.”

Today, he is able to encourage other young scientists to put these powerful tools to work.

In a nomination letter for the award, Thilo Behrends, associate professor of experimental biogeochemistry at Utrecht University, praised van Genuchten’s lab and field research as “extraordinary at this stage of his career.” He added, “I am also impressed with how van Genuchten has acted as an ambassador of synchrotron radiation, connecting young researchers and water companies to powerful synchrotron techniques.”

Removing arsenic from water with rust

Van Genuchten’s research focuses on removing a naturally occurring, yet highly toxic chemical element found in water: arsenic. In many countries, arsenic is naturally present in harmfully high levels in the groundwater. When people use this water to drink, prepare food or water crops, it results in health issues such as cancer, skin lesions and even death. Since arsenic is colorless, tasteless and odorless, people may be exposed without noticing until symptoms emerge.

The procedure van Genuchten developed is deceptively straightforward. After filling a large tank with groundwater, he adds large steel panels and connects them to a power supply. By inducing a current through the steel, he can create rust from the steel panels which can remove the arsenic from the water.

“Things started to get interesting when we found that simply by changing the way that we apply the current – if we do a high current at once for a small period of time versus a small current over a longer period of time – the type of rust that's produced changes,” he said.

There are many kinds of rust: white, green, black, brown, yellow and orange. Since each rust has a different chemical structure, each rust reacts differently with arsenic. To determine how arsenic binds to these different rust particles, van Genuchten used SSRL’s X-rays.

Van Genuchten’s team recently discovered that producing black rust, or magnetite, can be the most efficient. Magnetite is a naturally occurring mineral with an incredible property. “If you look on a molecular scale, the iron in magnetite has the same geometric shape as arsenic in water, meaning that when you produce magnetite in contaminated groundwater, arsenic in the water can enter the crystal of magnetite where iron usually would,” he said.

However, one of the technical challenges with arsenic is that it is a trace chemical, which makes it incredibly difficult to detect due to its low amounts, especially when arsenic is incorporated into magnetite. Standard detection techniques would not work. But at SSRL, the team used a method called X-ray absorption spectroscopy that can detect even the smallest amounts of arsenic.

In his nomination letter, Arslan Ahmad, research scientist at KWR Watercycle Research Institute, noted, “There is no other technique that could have provided this information, and without Case’s influence, we would not have known this kind of molecular-scale data was obtainable.”

Creating accessible technologies to improve drinking water

Van Genuchten was inspired by the challenges of removing arsenic from water in rural areas, where many industrial technologies cannot be applied. The team he works with has already built a facility in Kolkata using locally available material. By producing orange rust, the facility removes arsenic from the drinking water of a school. With his recent encouraging results using magnetite, van Genuchten hopes to create a new, more efficient system in the future.

“Arsenic has affected human health in rural areas of northeast India and Bangladesh, where there aren’t water lines or pipes, industrial infrastructure is minimal and people live very spread out," he said. "Technologies that work in California in large scale treatment systems aren't going to be applicable. You have to focus on technologies that can function in the context of society.”

Steel is plentiful and inexpensive in these areas; the power supply for this device can be as simple as a car battery or solar (photovoltaic) cell.

But the challenges go beyond the technology, van Genuchten said.

“Any time you implement technologies in decentralized areas, there are many variables that you can't take into account in the lab,” he said. “These variables have more to do with the socioeconomics of technology implementation. And that’s where working with experts comes into play; building relationships with local experts and the community served by the technology is absolutely fundamental.”

Potential solutions to arsenic-rich waste

Arsenic treatment plants offer another opportunity for van Genuchten’s research. After removing arsenic from groundwater, it becomes a sludge-mud material. To decrease the sludge volume, water is removed by drying it. This final product goes into a hazardous waste landfill, where methods are applied to manage arsenic leaching from the landfill. But if you are in an area without disposal methods, this becomes more complicated.

Looking to the future, van Genuchten said, “I would be so satisfied with my career if I could figure out what to do with arsenic-rich waste. In one study, we took the orange rust from the field and tracked how the iron oxide and arsenic changes as the sludge is used in other materials. What I really want to do is take the waste and turn it into something with economic value.”

Lytle Award winners give a presentation at the annual SSRL/LCLS Users’ Meeting. Van Genuchten will present at a special virtual event on Oct. 2.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.