Atomic ‘Trojan horse’ could inspire new generation of X-ray lasers and particle colliders

At SLAC’s FACET facility, researchers have produced an intense electron beam by ‘sneaking’ electrons into plasma, demonstrating a method that could be used in future compact discovery machines that explore the subatomic world.

By Manuel Gnida

How do researchers explore nature on its most fundamental level? They build “supermicroscopes” that can resolve atomic and subatomic details. This won’t work with visible light, but they can probe the tiniest dimensions of matter with beams of electrons, either by using them directly in particle colliders or by converting their energy into bright X-rays in X-ray lasers. At the heart of such scientific discovery machines are particle accelerators that first generate electrons at a source and then boost their energy in a series of accelerator cavities.

Now, an international team of researchers, including scientists from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, has demonstrated a potentially much brighter electron source based on plasma that could be used in more compact, more powerful particle accelerators.

The method, in which the electrons for the beam are released from neutral atoms inside the plasma, is referred to as the Trojan horse technique because it’s reminiscent of the way the ancient Greeks are said to have invaded the city of Troy by hiding their forceful soldiers (electrons) inside a wooden horse (plasma), which was then pulled into the city (accelerator).

“Our experiment shows for the first time that the Trojan horse method actually works,” says Bernhard Hidding from the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland, the principal investigator of a study published today in Nature Physics. “It’s one of the most promising methods for future electron sources and could push the boundaries of today’s technology.”

Replacing metal with plasma

In current state-of-the-art accelerators, electrons are generated by shining laser light onto a metallic photocathode, which kicks electrons out of the metal. These electrons are then accelerated inside metal cavities, where they draw more and more energy from a radiofrequency field, resulting in a high-energy electron beam. In X-ray lasers, such as SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), the beam drives the production of extremely bright X-ray light.

But metal cavities can only support a limited energy gain over a given distance, or acceleration gradient, before breaking down, and therefore accelerators for high-energy beams become very large and expensive. In recent years, scientists at SLAC and elsewhere have looked into ways to make accelerators more compact. They demonstrated, for example, that they can replace metal cavities with plasma that allows much higher acceleration gradients, potentially shrinking the length of future accelerators 100 to 1,000 times.

The new paper expands the plasma concept to the electron source of an accelerator.

“We’ve previously shown that plasma acceleration can be extremely powerful and efficient, but we haven’t been able yet to produce beams with high enough quality for future applications,” says co-author Mark Hogan from SLAC. “Improving beam quality is a top priority for the next years, and developing new types of electron sources is an important part of that.”

According to previous calculations by Hidding and colleagues, the Trojan horse technique could make electron beams 100 to 10,000 times brighter than today’s most powerful beams. Brighter electron beams would also make future X-ray lasers brighter and further enhance their scientific capabilities.

“If we’re able to marry the two major thrusts – high acceleration gradients in plasma and beam creation in plasma – we could be able to build X-ray lasers that unfold the same power over a distance of a few meters rather than kilometers,” says co-author James Rosenzweig, the principal investigator for the Trojan horse project at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Producing superior electron beams

The researchers carried out their experiment at SLAC’s Facility for Advanced Accelerator Experimental Tests (FACET). The facility, which is currently undergoing a major upgrade, generates pulses of highly energetic electrons for research on next-generation accelerator technologies, including plasma acceleration.

First, the team flashed laser light into a mixture of hydrogen and helium gas. The light had just enough energy to strip electrons off hydrogen, turning neutral hydrogen into plasma. It wasn’t energetic enough to do the same with helium, though, whose electrons are more tightly bound than those for hydrogen, so it stayed neutral inside the plasma.

Then, the scientists sent one of FACET’s electron bunches through the plasma, where it produced a plasma wake, much like a motorboat creates a wake when it glides through the water. Trailing electrons can “surf” the wake and gain tremendous amounts of energy.

In this study, the trailing electrons came from within the plasma (see animation above and movie below). Just when the electron bunch and its wake passed by, the researchers zapped the helium in the plasma with a second, tightly focused laser flash. This time the light pulse had enough energy to kick electrons out of the helium atoms, and the electrons were then accelerated in the wake.

The synchronization between the electron bunch, rushing through the plasma with nearly the speed of light, and the laser flash, lasting merely a few millionths of a billionth of a second, was particularly important and challenging, says UCLA’s Aihua Deng, one of the study’s lead authors: “If the flash comes too early, the electrons it produces will disturb the formation of the plasma wake. If it comes too late, the plasma wake has moved on and the electrons won’t get accelerated.”

The researchers estimate that the brightness of the electron beam obtained with the Trojan horse method can already compete with the brightness of existing state-of-the-art electron sources.

“What makes our technique transformative is the way the electrons are produced,” says Oliver Karger, the other lead author, who was at the University of Hamburg, Germany, at the time of the study. When the electrons are stripped off the helium, they get rapidly accelerated in the forward direction, which keeps the beam narrowly bundled and is a prerequisite for brighter beams.

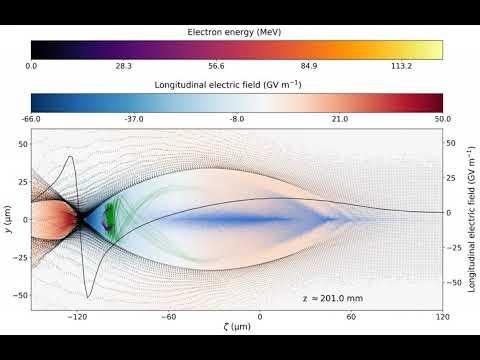

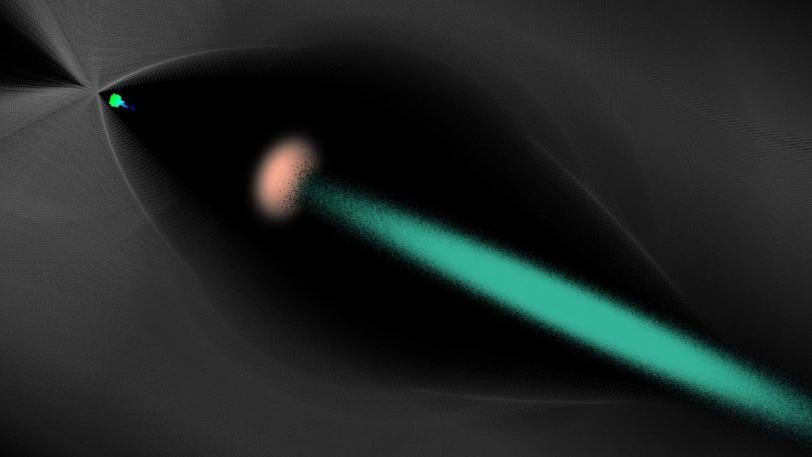

Trojan horse method, simulation

Computer simulation of the Trojan horse method. An electron bunch from SLAC’s FACET facility passed through hydrogen plasma and created a plasma bubble. A laser flash (dark red circular area) strips electrons off of neutral helium atoms (not shown) drifting inside the plasma. The released electrons are sucked into the tail of the bubble (trajectories shown in green), where they gain energy (color change from black to orange dots). The plasma bubble, shown stationary here, travels through the plasma with nearly the speed of light.

Daniel Ullmann and Andrew Beaton/University of Strathclyde

More R&D work ahead

But before applications like compact X-ray lasers could become a reality, much more research needs to be done.

Next, the researchers want to improve the quality and stability of their beam and work on better diagnostics that will allow them to measure the actual beam brightness, instead of estimating it.

These developments will be done once the FACET upgrade, FACET-II, is completed. “The experiment relies on the ability to use a strong electron beam to produce the plasma wake,” says Vitaly Yakimenko, director of SLAC’s FACET Division. “FACET-II will be the only place in the world that will produce such beams with high enough intensity and energy.”

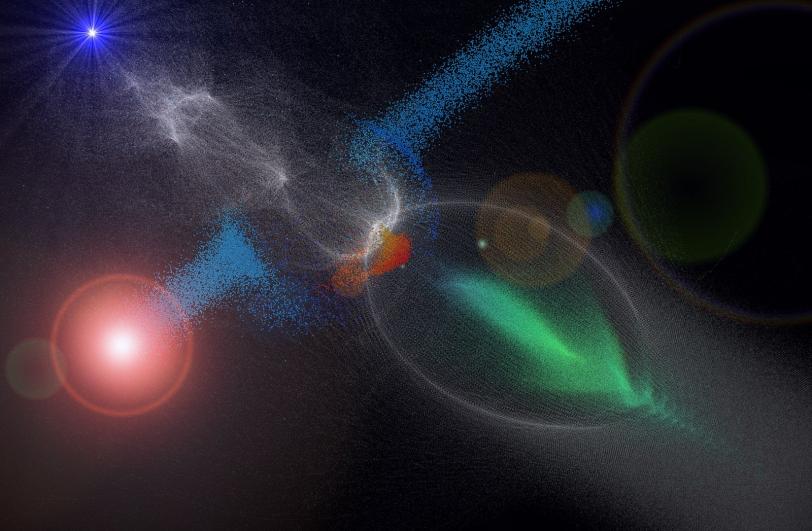

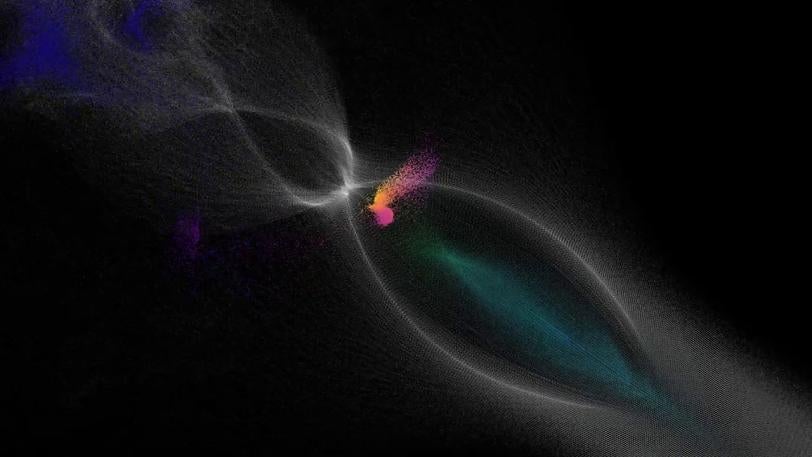

Trojan horse method, animation, perpendicular

Animation, based on simulations, of the Trojan horse technique for the production of high-energy electron beams in perpendicular geometry (90 degrees between laser and electron beams) as realized at SLAC. A laser beam (red, from right to left) strips electrons (blue dots) off of helium atoms. Some of the freed electrons (purplish to yellowish dots) get accelerated inside a plasma bubble (white elliptical shape) created by an electron beam (green).

Thomas Heinemann/University of Strathclyde

Trojan horse method, animation, collinear

Animation, based on simulations, of the Trojan horse technique for the production of high-energy electron beams in collinear geometry (laser and electron beams aligned). A focused laser beam (orange-red) strips electrons (initially blue dots) off of helium atoms. All these freed electrons get accelerated (visualized by increasingly green color) inside a plasma bubble (white elliptical shape) created by an electron beam (green).

Thomas Heinemann, Andrew Beaton/University of Strathclyde

Other partners involved in the project were Sci-Tech Daresbury, UK; the German research center DESY; the University of Colorado Boulder; the University of Oslo, Norway; the University of Texas at Austin; RadiaBeam Technologies; RadiaSoft LLC; and Tech-X Corporation. Large parts of this work were funded by the DOE Office of Science. LCLS and FACET are DOE Office of Science user facilities.

Citation: A. Deng, O. Karger, et al., Nature Physics, 12 August 2019 (10.1038/s41567-019-0610-9)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.