A quick liquid flip helps explain how morphing materials store information

Experiments at SLAC’s X-ray laser reveal in atomic detail how two distinct liquid phases in these materials enable fast switching between glassy and crystalline states that represent 0s and 1s in memory devices.

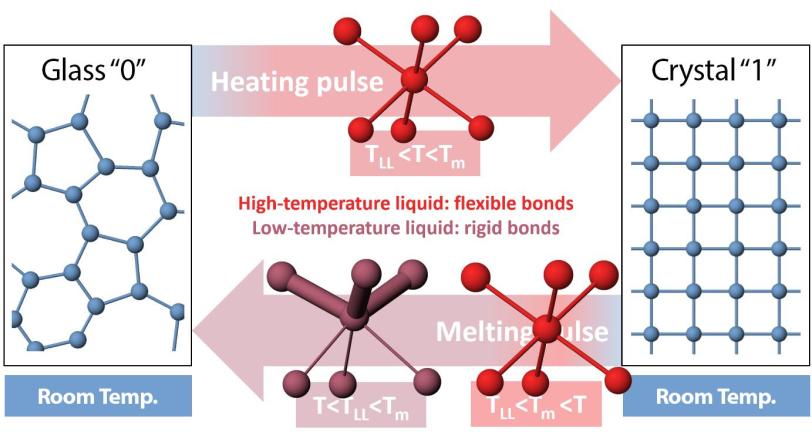

Instead of flash drives, the latest generation of smart phones uses materials that change physical states, or phases, to store and retrieve data faster, in less space and with more energy efficiency. When hit with a pulse of electricity or optical light, these materials switch between glassy and crystalline states that represent the 0s and 1s of the binary code used to store information.

Now scientists have discovered how those phase changes occur on an atomic level.

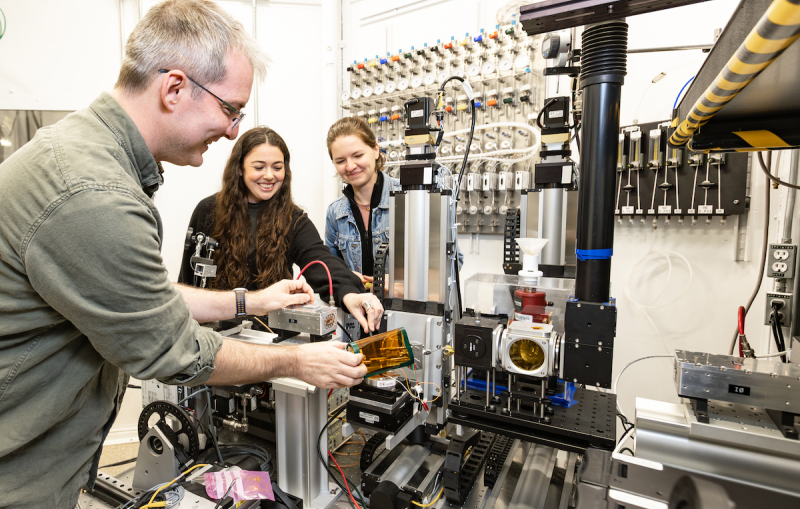

Researchers from European XFEL and the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany, working in collaboration with researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, led X-ray laser experiments at SLAC that collected more than 10,000 snapshots of phase-change materials transforming from a glassy to a crystalline state in real time.

They discovered that just before the material crystallizes, it changes from one liquid-like state to another, a process that could not be clearly seen in prior studies because it was blurred by the rapid motions of the atoms. And they showed that this transition is responsible for the material's unique ability to store information for long periods of time while also quickly switching between states.

The results, published in Science today, offer a new strategy for designing improved phase-change materials for specialized memory storage.

“Current data storage technology has reached a scaling limit, so that new concepts are required to store the amounts of data that we will produce in the future,” said Peter Zalden, a scientist at European XFEL and lead author of the study. “Our study explains how the switching process in a promising new technology can be fast and reliable at the same time.”

When stable becomes unstable

The experiments took place at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) which produces X-ray laser pulses that are short enough and intense enough to capture snapshots of atomic changes occurring in femtoseconds – millionths of a billionths of a second.

To store information with phase-change materials, they must be cooled quickly to enter a glassy state without crystallizing, and remain in this glassy state as long as the information needs to stay there. This means the crystallization process must be very slow to the point of being almost absent, such as is the case in ordinary glass. But when it comes time to erase the information, which is done by applying high temperatures, the same material has to crystallize very quickly. The fact that a material can form a stable glass but then become very unstable at elevated temperatures has puzzled researchers for decades.

At LCLS, the scientists used an optical laser to rapidly heat amorphous films of phase-change materials, just 50 nanometers thick, atop an equally thin support. The films cooled into a crystalline state as the heat from the laser blast dissipated into the surrounding support structure over billionths of a second.

They used X-ray laser pulses to make images of the material’s structural evolution, collecting each snapshot in the instant before a sample deteriorated.

A tale of two liquids

The researchers found that when the liquid cools far enough below the material’s melting temperature, it undergoes a structural change to form another, lower-temperature liquid that exists for just billionths of a second.

The two liquids not only have very different atomic structures, but they also behave differently: The one at higher temperature has highly mobile atoms that can quickly arrange themselves into the well-ordered structure of a crystal. But in the lower-temperature liquid, some chemical bonds become stronger and more rigid and can hold the disordered atomic structure of the glass in place. It is only the rigid nature of these chemical bonds that keeps the glass from crystallizing and – in the case of phase-change memory devices – secures information in place. The results also help scientists understand how other classes of materials form a glass.

This article is based on a press release from European XFEL.

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility, and SLAC co-authors Aaron Lindenberg, David Reis and Mariano Trigo are investigators with the Stanford PULSE Institute and the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES). This study was part of an international collaboration including scientists from European XFEL, Forschungszentrum Jülich, Institut Laue-Langevin, the DOE’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Lund University, Paul Scherrer Institute, Stanford University, The Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), University of Aachen, University of Duisburg-Essen and the University of Potsdam.

Major funding was provided by the German Research Council, the European Union (7th Framework Program) and the DOE Office of Science Office of Basic Energy Sciences (Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering).

Citation: P. Zalden et al., Science, 13 June 2019 (10.1126/science.aaw1773)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit energy.gov/science.