First direct view of an electron’s short, speedy trip across a border

Watching electrons sprint between atomically thin layers of material will shed light on the fundamental workings of semiconductors, solar cells and other key technologies.

By Glennda Chui

Electrons flowing across the boundary between two materials are the foundation of many key technologies, from flash memories to batteries and solar cells. Now researchers have directly observed and clocked these tiny cross-border movements for the first time, watching as electrons raced seven-tenths of a nanometer – about the width of seven hydrogen atoms – in 100 millionths of a billionth of a second.

Led by scientists at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University, the team made these observations by measuring tiny bursts of electromagnetic waves given off by the traveling electrons – a phenomenon described more than a century ago by Maxwell’s equations, but only now applied to this important measurement.

“To make something useful, generally you need to put different materials together and transfer charge or heat or light between them,” said Eric Yue Ma, a postdoctoral researcher in the laboratory of SLAC/Stanford Professor Tony Heinz and lead author of a report in Science Advances.

“This opens up a new way to measure how charge – in this case, electrons and holes – travels across the abrupt interface between two materials,” he said. “It doesn’t just apply to layered materials. For instance, it can also be used to look at electrons flowing between a solid surface and molecules that are attached to it, or even, in principle, between a liquid and a solid.”

Too short, too fast – or were they?

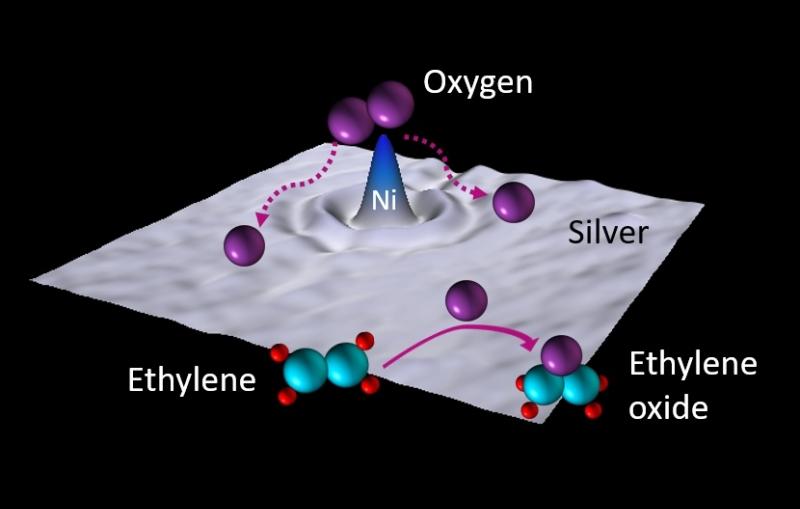

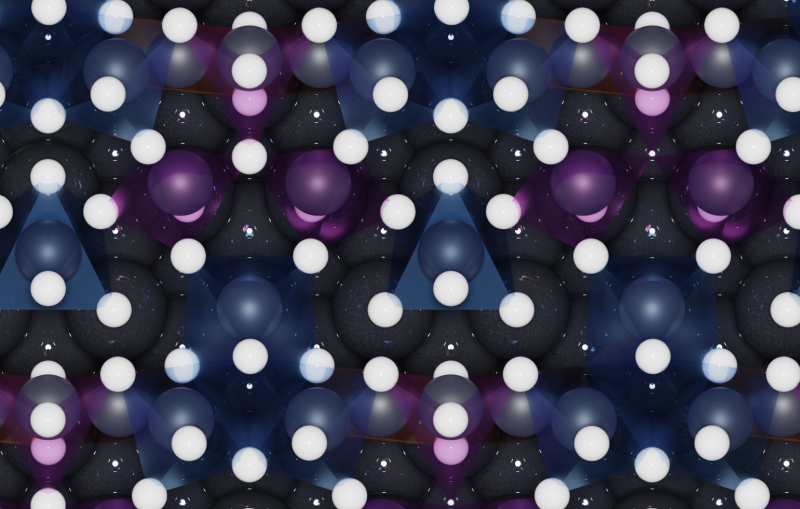

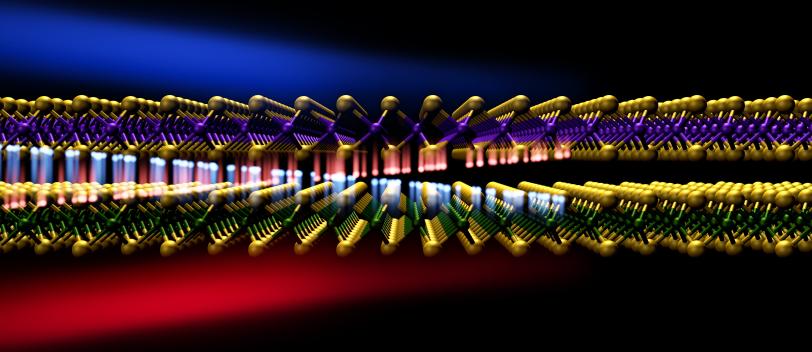

The materials used in this experiment are transition metal dichalcogenides, or TMDCs – an emerging class of semiconducting materials that consist of layers just a few atoms thick. There’s been an explosion of interest in TMDCs over the past few years as scientists explore their fundamental properties and potential uses in nanoelectronics and photonics.

When two types of TMDC are stacked in alternating layers, electrons can flow from one layer to the next in a controllable way that people would like to harness for various applications.

But until now, researchers who wanted to observe and study that flow had only been able to do it indirectly, by probing the material before and after the electrons had moved. The distances involved were just too short, and the electron speeds too fast, for today’s instruments to catch the flow of charge directly.

At least that’s what they thought.

Maxwell leads the way

According to a famous set of equations named after physicist James Clerk Maxwell, pulses of current give off electromagnetic waves, which can vary from radio waves and microwaves to visible light and X-rays. In this case, the team realized that an electron’s journey from one TMDC layer to another should generate blips of terahertz waves – which fall between microwaves and infrared light on the electromagnetic spectrum – and that those blips could be detected with today’s state-of-the-art tools.

“People had probably thought of this before, but dismissed the idea because they thought there was no way you could measure the current from electrons traveling such a small distance in such a small amount of material,” Ma said. “But if you do a back-of-the-envelope calculation, you see that if a current is really that fast you should be able to measure the emitted light, so we just tried.”

Nudges from a laser

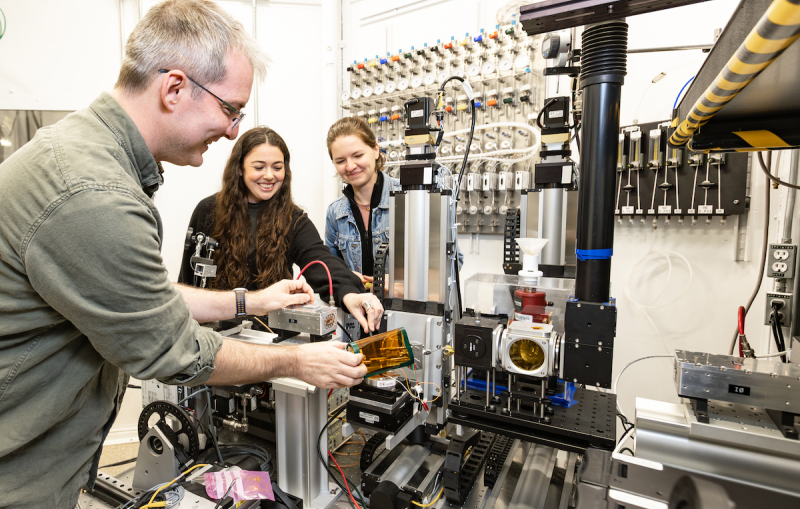

The researchers, all investigators with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC, tested their idea on a TMDC material made of molybdenum disulfide and tungsten disulfide.

Working with SLAC/Stanford Professor Aaron Lindenberg, Ma and fellow postdoc Burak Guzelturk hit the material with ultrashort pulses of optical laser light to get the electrons moving and recorded the terahertz waves they gave off with a technique called time-domain terahertz emission spectroscopy. Those measurements not only revealed how far and fast the electric current traveled between layers, Ma said, but also the direction it traveled in. When the same two materials were stacked in reverse order, the current flowed in exactly the same way but in the opposite direction.

“With the demonstration of this new technique, many exciting problems can now be addressed,” said Heinz, who led the team’s investigation. “For example, rotating one of the two crystal layers with respect to the other is known to dramatically change the electronic and optical properties of the combined layers. This method will allow us to directly follow the rapid motion of electrons from one layer to the other and see how this motion is affected by the relative positioning of the atoms.”

Major funding for this work came from the DOE Office of Science and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The samples of material the team studied were grown at North Carolina State University.

Citation: Ma et al., Science Advances 8 February 2019 (10.1126/sciadv.aau0073)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.