Q&A: Al Ashley Reflects on His Efforts to Diversify SLAC and Beyond

An award-winning mentor and networking guru, Al Ashley has placed thousands of underrepresented minority students in science and engineering summer research programs.

By Jennifer Huber

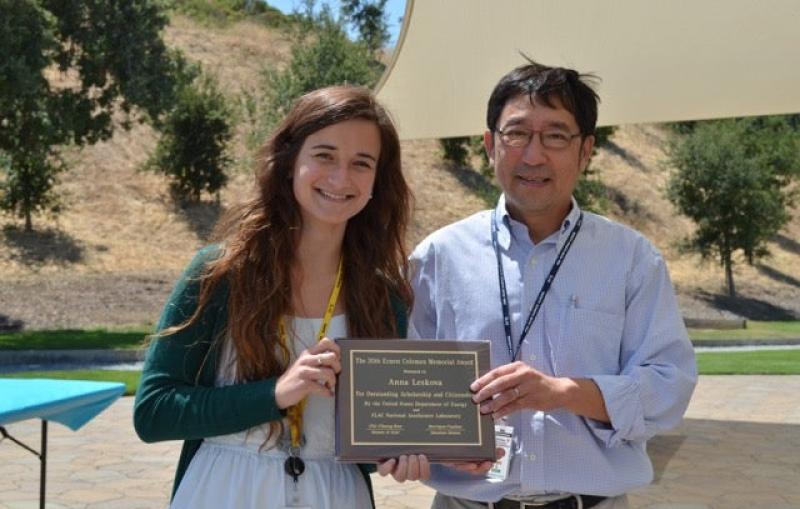

Over the 31 years that Al Ashley worked as a human resources representative at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, he pioneered many programs that promoted diversity and encouraged career development for employees and talented students. He established SLAC’s charter membership in the National Consortium for Graduate Degrees for Minorities in Science and Engineering. He also developed the SLAC Summer Science Research Program for underrepresented minority undergraduates in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Today, SLAC runs the Alonzo W. Ashley Internship Program, named in honor of Ashley and his legacy of championing diversity.

Ashley has placed thousands of underrepresented minority students in summer research programs and personally mentored hundreds of these emerging scientists and engineers. In recognition of his outstanding efforts, he received the 2005 National Science Foundation Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Mathematics and Engineering Mentoring.

We spoke with Ashley about his career at SLAC and his continued efforts in Arkansas to guide more minority students into successful science and engineering careers.

Why is diversity in science and engineering important?

Diversity matters a great deal. It helps students and science itself, by including voices from all sides. Diverse participation makes this country better.

Back in 1968 when I started working at SLAC, most of the laboratories and universities had very few minorities and women. This was shortly after the assassination of Martin Luther King and during the Vietnam War. Students across the country were demanding more minority students, faculty members and administrators. So, the timing was right. At SLAC there was a void of minority scientists, particularly African Americans. We needed to do something about it.

We had a team of dedicated people at the time. I always felt that Deputy Director Sid Drell was my coach, and I was the quarterback. First, in 1969, we invited six minority faculty members from historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) to come to SLAC for an all-expenses-paid fellowship. And then in 1970, we developed a program called the Summer Science Research Program. And that was the beginning.

We’ve come a long way, because many government laboratories and universities are trying to even the playing field by increasing the number of minority students getting involved in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, or STEM.

How did you recruit and retain minority students?

If our kids are going to compete in the 21st century, they must be involved in programs that include three elements: mentoring, networking and summer research opportunities. I strongly believe that the combination of all three of these components is the key to the success of a student, especially in STEM.

In terms of recruitment, I went to places SLAC had never gone before – small historically black colleges, like Dillard University in New Orleans and Norfolk State University in Virginia. I found diamonds in the rough at these small colleges.

I also recruited at conferences, including black, Hispanic and Native American science and engineering conferences – such as the National Society of Black Engineers conference, which hosts about 8,500 students every year.

That’s where I recruited SLAC employee Dorian Bohler. When he was a freshman, I saw him in the hall with several friends at a conference. I asked if they needed internships and they said yes, so I made calls right then. A few days later, they had all applied and gotten a summer internship. And they are doing well today.

Another way I got people into programs was by talking to their mentors at school, because they usually followed their mentors’ guidance.

I also found professors who had their own grant money to send students to SLAC. In the early 1970s, we invited out a professor who used his own grant money to bring along five physics students to SLAC every summer for about five years. Then a professor from Florida A&M University asked to do the same thing, and it took off from there.

After I retired, I developed a partnership with SLAC and four HBCUs. When faculty and students can spend a summer at national laboratories, it makes both parties better. It’s a win-win situation.

As an award-winning mentor, what tips can you give other mentors?

You have to develop a very good relationship with the students. The students must trust that you’re acting in their best interests. And that you’re working to move them, and even their families, up the ladder of success.

You also have to be persistent and dedicated to the cause of elevating that student to the best that he can be, and that can take a lot of work sometimes, keeping in touch with the student on a consistent basis for years.

Finally, building up a large network is critical. I’ve been providing opportunities for students in math and science for 50 years – across two generations of mentees – so I can pick up the phone and use this network to find students an internship.

One time, a student came to see me at Stanford wanting a job. He told me that he lived in Little Rock, Arkansas, and his mother wouldn’t let him stay in California all summer unless he had a job. I called his mother to assure her that I’d find a job for her son. Later, I called and spoke to his father to let him know his son was doing okay at SLAC. His father told me that I’d gotten him a job at SLAC 22 years earlier, and that I helped all three of his daughters get jobs at Stanford. I had helped the whole family get jobs, but I didn’t know two of them personally. It was amazing.

What are you doing now?

SLAC was just the beginning. I founded a program here in Arkansas in 2004 called the Arkansas Mentoring and Networking Association. We teach high school students about networking, mentor-mentee relationships and summer intern and research opportunities. We’ve placed more than 300 students in summer internships across the country at top schools. We’ve also invited speakers, including physicist and former SLAC Director Burton Richter, to talk to the students at the HBCUs in Arkansas. And all of these speakers paid their own expenses to come to Little Rock, because they know it’s important.

I also serve on the External Advisory STEM Council of the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. I place students in about 20 internships across the country every year.

Do you think we can ever achieve full diversity in STEM?

We still have a long way to go, but we can try. A lot of universities are trying to give students a STEM education. A lot of universities offer summer research programs, exchange programs and things of that nature. All of these things will help. If we don't reach that goal, we can get close.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.