Scientists, Interns Bring Structural Biology’s ‘Magic Bullet’ Technique to X-ray Lasers

Experiment Pushes SLAC's LCLS to Highest Energy Yet

To understand the three-dimensional shape of a protein, scientists often rely on information from similar molecules. But sometimes, the protein is so unique that it’s not possible to find a close relative.

In these instances, there’s an imaging tool available called “de novo phasing”. Researchers tag the molecule with an element that gives a characteristic signal and allows them to deduce the fine details of the complex 3-D structure of the protein.

A recent study at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory successfully used this technique at an X-ray free-electron laser for the first time with the element selenium as a marker. The scientists were able to swap selenium with the natural sulfur in biotin, which they then bound to the biomolecule streptavidin, a protein produced by bacteria.

“This selenium phasing technique is called ‘the magic bullet of structural biology’ because it’s very powerful,” says Mark Hunter, SLAC scientist. “It gives a very strong signal and it’s often simple to incorporate selenium into a biological structure.”

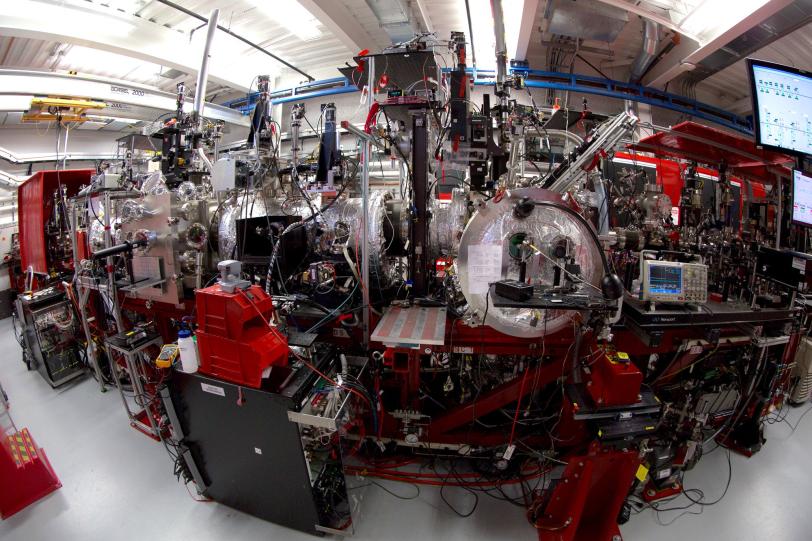

Using 330,000 images captured by the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), a DOE Office of Science User Facility, the research team determined the structure of the molecule from the data alone. Nature Communications published the study on Nov. 4.

Although the structure of the biotin-streptavidin compound is known, this information was not used, and the experiment shows the technique can be applied to unknown structures.

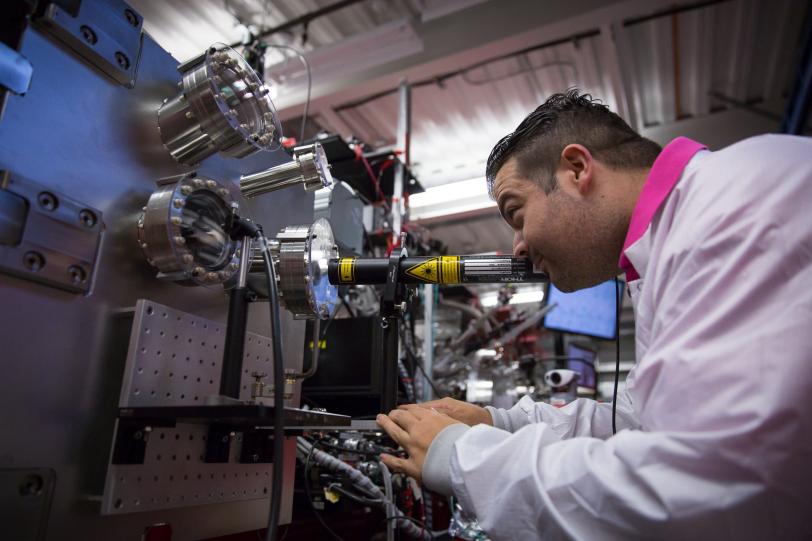

Seven of the co-authors on the paper were students in the 2015 summer LCLS intern program, managed by Alan Fry, director of the LCLS Laser Science and Technology Division. The interns prepared samples, ran trials and helped collect data during the study.

The experiment required the X-ray laser to work at its highest energy to-date, 12.8 keV, to get the characteristic signal from the bound selenium. “We had every single accelerating part of LCLS running,” says Chun Hong Yoon, lead data analyst for the project. “The accelerator physicists have found ways of really increasing the output, in terms of photon energy. If there had been any failures, we would not have been able to do the work.”

Selenium phasing is commonly used at synchrotrons, another bright source of light for X-ray experiments. This experiment marks the first time scientists have been able to use selenium for de novo phasing at an X-ray free-electron laser. Previous experiments at SLAC have used heavy metal atoms or sulfur as a marker for phasing.

If a sample is radiation-sensitive, it can be difficult to do the experiment at a synchrotron, where X-ray pulses tend to be longer and samples may be damaged during the measurement. Now, scientists can take advantage of the short, bright pulses of LCLS to conduct phasing studies with selenium, while greatly reducing the risk of conventional radiation damage that can complicate the results.

In the future, the LCLS researchers would like to develop a way to solve structures with fewer images, shortening the time required to conduct these types of experiments.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.