Prototype of LUX-ZEPLIN Dark Matter Detector Tested at SLAC

A small-scale version of the future detector allows researchers and engineers to test, develop and troubleshoot various aspects of its technology.

Prototyping of a new, ultrasensitive “eye” for dark matter is making rapid progress at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory: Researchers and engineers have installed a small-scale version of the future LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) detector to test, develop and troubleshoot various aspects of its technology.

When LZ goes online in early 2020 at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota, hopes are that it will detect so-called weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs. Many researchers believe that these hypothetical particles could make up the dark matter, the invisible substance that accounts for 85 percent of all matter in the universe.

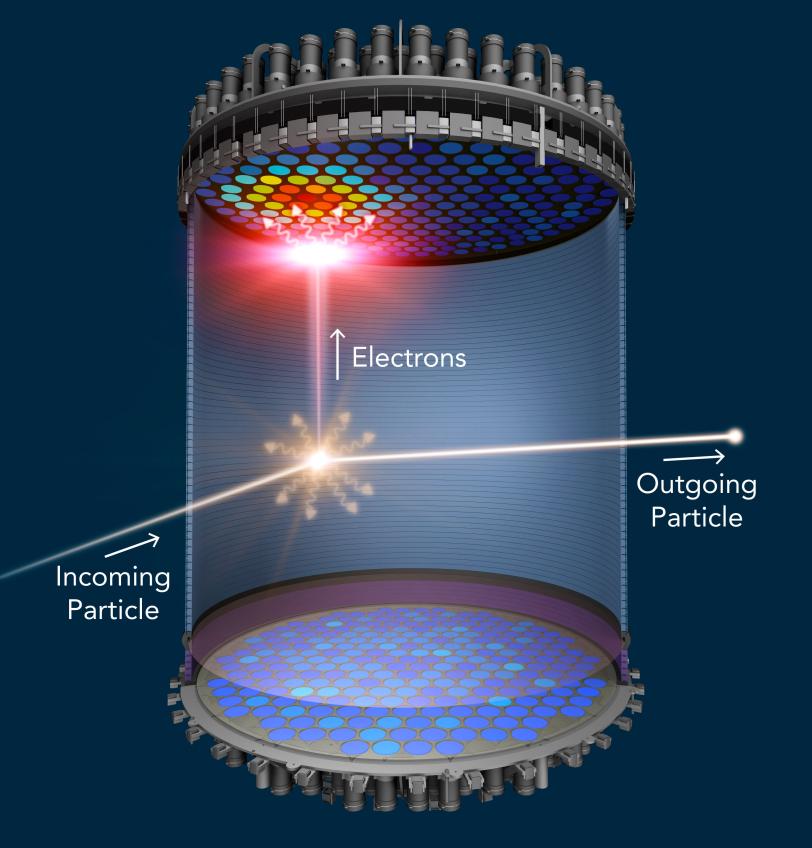

The detector’s core will be a 5-foot-tall container filled with 10 tons of liquid xenon. When particles pass through it and collide with a xenon atom, the xenon atom emits a flash of light and also releases electrons, which generate a second flash of light. These two consecutive light flashes could represent a characteristic WIMP signal, if all other possible origins have been ruled out.

One particular challenge is to create a strong, stable electric field across the vessel to quickly pull all electrons to the top, where they can be detected. This requires applying high voltages over short distances at the bottom and top of the xenon container. However, it also produces unwanted stray light and can cause damaging electric sparks if not done properly.

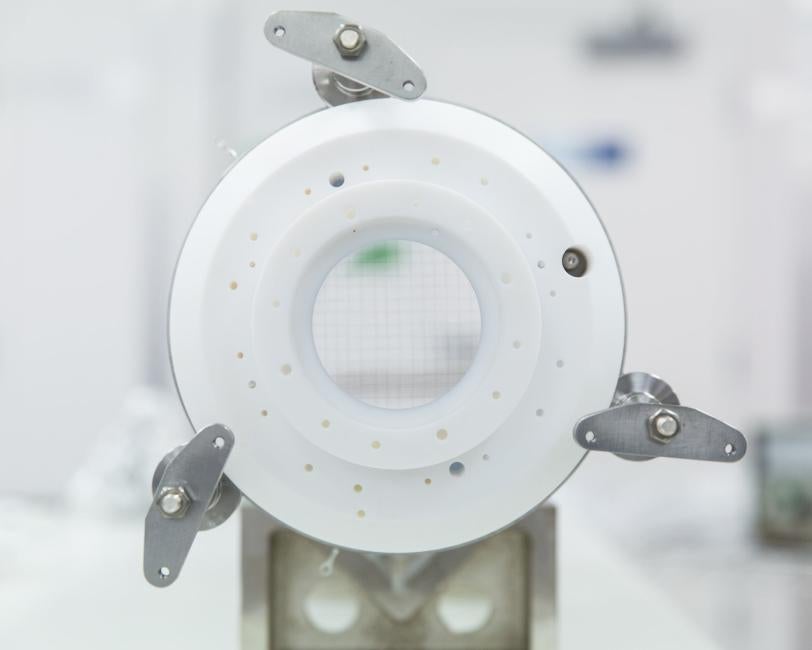

So the SLAC team is now carefully testing the design of the high-voltage system on a 20-inch-tall miniversion of the xenon vessel whose parts were manufactured by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which manages the LZ project.

“We began testing the bottom part last year and have now assembled the entire prototype,” says Kimberly Palladino, an LZ scientist at SLAC and assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. “Our goal is to reach high voltages of 100 kilovolts without sparking, demonstrate that the system runs stably over time, and reduce the stray emissions we’ve been observing.”

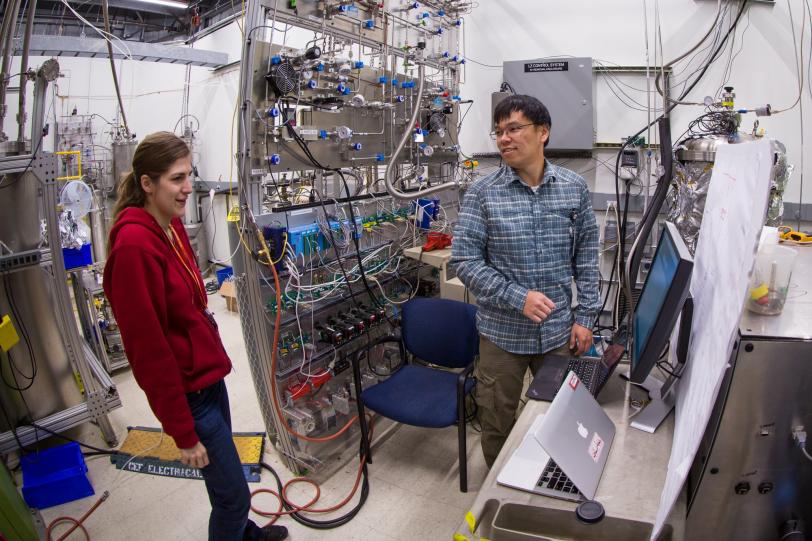

SLAC research associate Tomasz Biesiadzinski says, “In addition, we use our test stand to test all kinds of aspects of LZ, including the cooling system, xenon purification and circulation, control systems and sensors. Researchers from various groups around the world come here, too, to test the equipment they are developing for the experiment.”

In parallel, SLAC’s team is working on a system to remove an isotope of the chemical element krypton that would cause unwanted signals in the LZ detector from commercially available xenon. The goal: Reach a level of 15 krypton atoms or less per one million billion xenon atoms. Once the design goal has been reached, the researchers will build a large-scale system to purify all 10 tons of xenon needed for the experiment.

To learn more about the project, visit the website of SLAC’s LZ team, which is part of the lab’s Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology Division and SLAC’s/Stanford University’s Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC). The team works closely with a number of LZ collaborators, including Berkeley Lab, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Texas A&M University, University of Maryland, Oxford University and University of Wisconsin.

Visit the SLAC LZ Group Website

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.