Major Upgrade Will Boost Power of World’s Brightest X-ray Laser

Upgrade will sharpen our view of nature’s atomic processes at work, aiding the development of a number of transformative technologies.

Menlo Park, Calif. — Construction begins today on a major upgrade to a unique X-ray laser at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. The project will add a second X-ray laser beam that’s 10,000 times brighter, on average, than the first one and fires 8,000 times faster, up to a million pulses per second.

The project, known as LCLS-II, will greatly increase the power and capacity of SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) for experiments that sharpen our view of how nature works on the atomic level and on ultrafast timescales.

“LCLS-II will take X-ray science to the next level, opening the door to a whole new range of studies of the ultrafast and ultrasmall,” said LCLS Director Mike Dunne. “This will tremendously advance our ability to develop transformative technologies of the future, including novel electronics, life-saving drugs and innovative energy solutions.”

SLAC Director Chi-Chang Kao said, “Our lab has a long tradition of building and operating premier X-ray sources that help users from around the world pursue cutting-edge research in chemistry, materials science, biology and energy research. LCLS-II will keep the U.S. at the forefront of X-ray science.”

LCLS-II: The Next Leap for X-ray Science

Introducing LCLS-II, a future light source at SLAC. It will generate over 8,000 times more light pulses per second than today’s most powerful X-ray laser, LCLS, and produce an almost continuous X-ray beam that on average will be 10,000 times brighter. These unrivaled capabilities will help researchers address a number of grand challenges in science by capturing detailed snapshots of rapid processes that are beyond the reach of other light sources.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

A Superior X-ray Microscope

When LCLS opened six years ago as a DOE Office of Science User Facility, it was the first light source of its kind – a unique X-ray microscope that uses the brightest and fastest X-ray pulses ever made to provide unprecedented details of the atomic world.

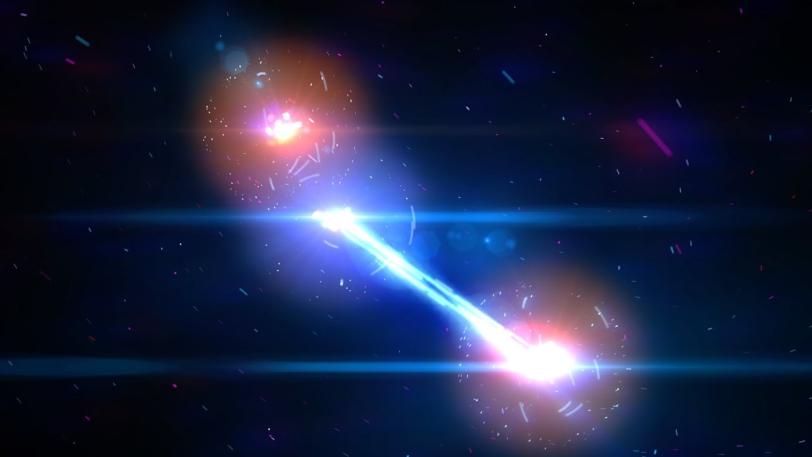

Hundreds of scientists use LCLS each year to catch a glimpse of nature’s fundamental processes in unprecedented detail. Molecular movies reveal how chemical bonds form and break; ultrafast snapshots capture electric charges as they rapidly rearrange in materials and change their properties; and sharp 3-D images of disease-related proteins provide atomic-level details that could hold the key for discovering potential cures.

The new X-ray laser will work in parallel with the existing one, with each occupying one-third of SLAC’s 2-mile-long linear accelerator tunnel. Together they will allow researchers to make observations over a wider energy range, capture detailed snapshots of rapid processes, probe delicate samples that are beyond the reach of other light sources and gather more data in less time, thus greatly increasing the number of experiments that can be performed at this pioneering facility.

“The upgrade will benefit X-ray experiments in many different ways, and I’m very excited to use the new capabilities for my own research,” said Brown University Professor Peter Weber, who co-led an LCLS study that used X-ray scattering to track ultrafast structural changes as ring-shaped gas molecules burst open in a chemical reaction vital to many processes in nature. “With LCLS-II, we’ll be able to bring the motions of atoms much more into focus, which will help us better understand the dynamics of crucial chemical reactions.”

A Big Leap in X-ray Laser Performance

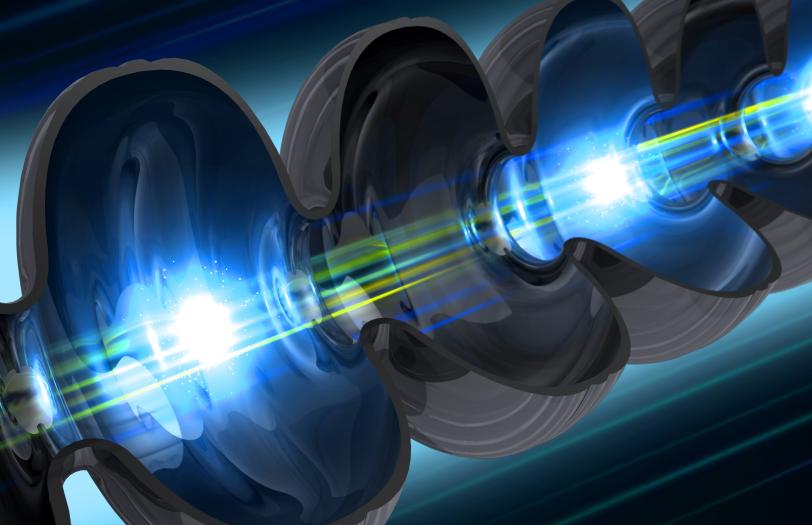

Like the existing facility, LCLS-II will use electrons accelerated to nearly the speed of light to generate beams of extremely bright X-ray laser light. The electrons fly through a series of magnets, called an undulator, that forces them to travel a zigzag path and give off energy in the form of X-rays.

But the way those electrons are accelerated will be quite different, and give LCLS-II much different capabilities.

At present, electrons are accelerated down a copper pipe that operates at room temperature and allows the generation of 120 X-ray laser pulses per second.

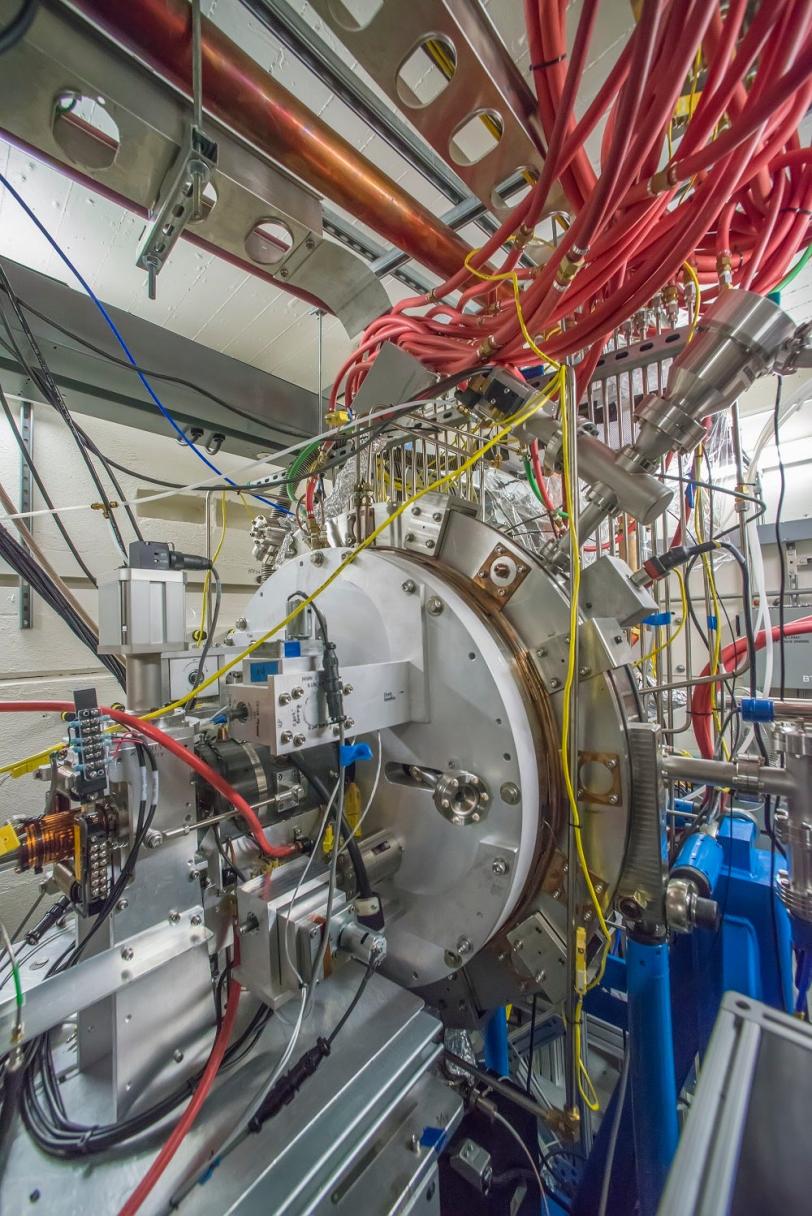

For LCLS-II, crews will install a superconducting accelerator. It’s called “superconducting” because its niobium metal cavities conduct electricity with nearly zero loss when chilled to minus 456 degrees Fahrenheit. Accelerating electrons through a series of these cavities allows the generation of an almost continuous X-ray laser beam with pulses that are 10,000 times brighter, on average, than those of LCLS and arrive up to a million times per second.

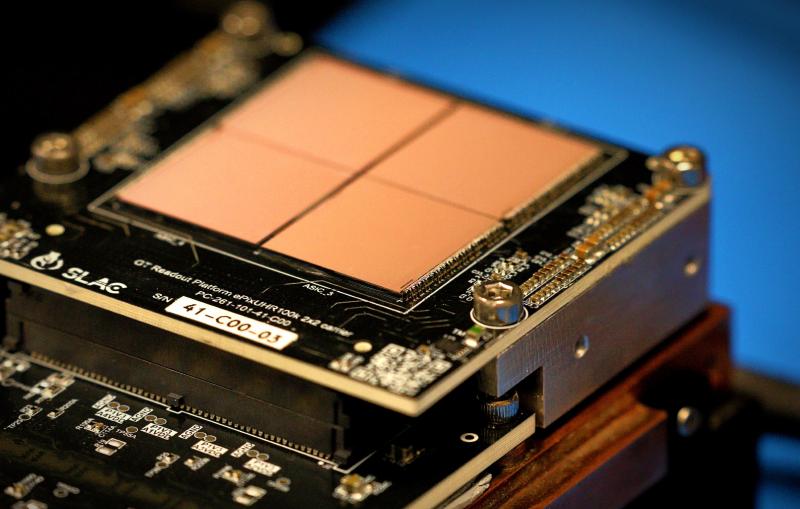

In addition to a new accelerator, LCLS-II requires a number of other cutting-edge components, including a new electron source, two powerful cryoplants that produce refrigerant for the niobium structures, and two new undulators to generate X-rays.

Strong Partnerships for a Bright Future in X-ray Science

To make this major upgrade a reality, SLAC has teamed up with four other national labs – Argonne, Berkeley Lab, Fermilab and Jefferson Lab – and Cornell University, with each partner making key contributions to project planning as well as to component design, acquisition and construction.

“We couldn’t do this without our collaborators,” said SLAC’s John Galayda, head of the LCLS-II project team. “To bring all the components together and succeed, we need the expertise of all partners, their key infrastructure and the commitment of their best people.”

With favorable “Critical Decisions 2 and 3 (CD-2/3)” in March, DOE has formally approved construction of the $1 billion project, which is being funded by DOE’s Office of Science. SLAC is now clearing out the first third of the linac to make room for the superconducting accelerator, which is scheduled to begin operations in the early 2020s. In the meantime, LCLS will continue to serve the X-ray science community, except for a construction-related, six-month downtime in 2017 and a 12-month shutdown extending from 2018 into 2019.

With the upgrades that are now moving forward, Dunne said, SLAC will have an X-ray laser facility that will enable groundbreaking research for years to come.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.