Scientists Use X-rays to Look at How DNA Protects Itself from UV Light

DNA’s molecular building blocks absorb ultraviolet light so strongly that sunlight should deactivate them – yet it doesn’t. A new SLAC study reveals details of a “relaxation response” that protects these molecules and the genetic information they encode.

Menlo Park, Calif. — The molecular building blocks that make up DNA absorb ultraviolet light so strongly that sunlight should deactivate them – yet it does not. Now scientists have made detailed observations of a “relaxation response” that protects these molecules, and the genetic information they encode, from UV damage.

The experiment at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory focused on thymine, one of four DNA building blocks. Researchers hit thymine with a short pulse of ultraviolet light and used a powerful X-ray laser to watch the molecule’s response: A single chemical bond stretched and snapped back into place within 200 quadrillionths of a second, setting off a wave of vibrations that harmlessly dissipated the destructive UV energy.

The international research team reported the results June 23 in Nature Communications.

While protecting the genetic information encoded in DNA is vitally important, the significance of this result goes far beyond DNA chemistry, said Philip Bucksbaum, director of the Stanford PULSE Institute and a co-author of the report.

“The new tool the team developed for this study provides a new window on the motion of electrons that control all of chemistry,” he said. “We think this will enhance the value and impact of X-ray free-electron lasers for important problems in biology, chemistry and physics.”

Light Becomes Heat

Researchers had noticed years ago that thymine seemed resistant to damage from UV rays in sunlight, which cause sunburn and skin cancer. Theorists proposed that thymine got rid of the UV energy by quickly shifting shape. But they differed on the details, and previous experiments could not resolve what was happening.

The SLAC experiment took place at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), a DOE Office of Science user facility, whose bright, ultrashort X-ray laser pulses can see changes taking place at the level of individual atoms in quadrillionths of a second.

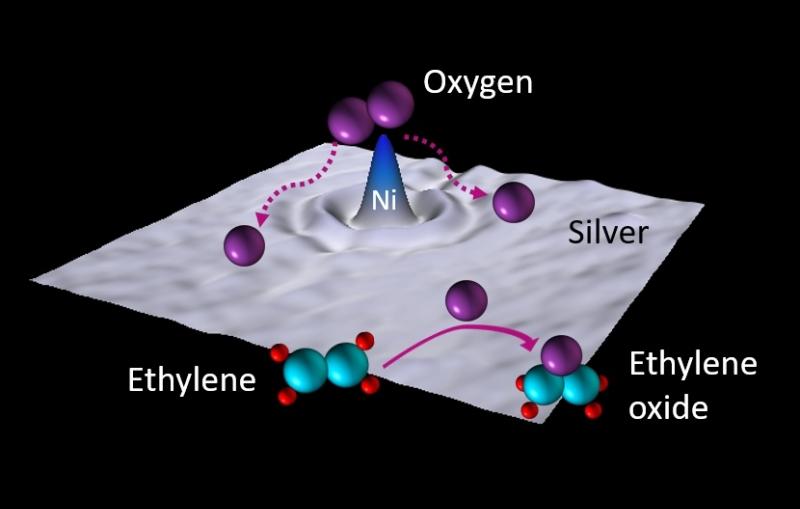

Scientists turned thymine into a gas and hit it with two pulses of light in rapid succession: first UV, to trigger the protective relaxation response, and then X-rays, to detect and measure the response.

“As soon as the thymine swallows the light, the energy is funneled as quickly as possible into heat, rather than into making or breaking chemical bonds,” said Markus Guehr, a DOE Early Career Program recipient and senior staff scientist at PULSE who led the study. “It’s like a system of balls connected by springs; when you elongate that one bond between two atoms and let it loose, the whole molecule starts to tremble.”

Ejected Electrons Signal Changes

The X-rays measured the relaxation response indirectly by stripping away some of the innermost electrons from atoms in the thymine molecule. This sets off a process known as Auger decay that ultimately ejects other electrons. The ejected electrons fly into a detector, carrying information about the nature and state of their home atoms.

By comparing the speeds of the ejected electrons before and after thymine was hit with UV, the researchers were able to pinpoint rapid changes in a single carbon-oxygen bond: It stretched when hit with UV light and shortened 200 quadrillionths of a second later, setting off vibrations that continued for billionths of a second.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to distinguish between two fundamental responses in the molecule – movements of the atomic nuclei and changes in the distribution of electrons – and time them within a few quadrillionths of a second,” said the paper’s first author, Brian McFarland, a postdoctoral researcher who has since moved from SLAC to Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Guehr said the team plans more experiments to further explore the protective relaxation response and extend the new method, called time-resolved Auger spectroscopy, into other scientific realms.

In addition to the Stanford PULSE Institute, which is a joint institute of SLAC and Stanford University, the study included researchers from LCLS, Stanford, the University of Perugia in Italy, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the University of Connecticut, Western Michigan University, the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, and UNIST in South Korea. Parts of the research were carried out at Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source, a DOE Office of Science user facility. The work was funded by the DOE Office of Science, the Swedish Research Council, the Göran Gustafsson Foundation and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Citation: B. K. McFarland, J. P. Farrell et al., Nature Communications, 23 June 2014 (10.1038/ncomms5235)

Press Office Contact: Andrew Gordon, agordon@slac.stanford.edu, (650) 926-2282

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The Stanford PULSE Institute is a joint institute of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University. PULSE seeks to advance the frontiers of ultrafast science, with particular emphasis on research using SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). For more information, please visit www.stanford.edu/group/pulse_institute.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.