A New Way to Create Compact Light Sources

SLAC scientists have found a new way to produce bright pulses of light from accelerated electrons that could shrink "light source" technology used around the world since the 1970s to examine details of atoms and chemical reactions.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

SLAC scientists have found a new way to produce bright pulses of light from accelerated electrons that could shrink "light source" technology used around the world since the 1970s to examine details of atoms and chemical reactions.

Traditionally this light is created by wiggling accelerated electrons with heavy magnets in a device called an undulator. Undulators currently produce bright X-ray pulses for experiments at dozens of sites, including SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) and Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) free-electron X-ray laser. The new approach replaces the magnets with microwaves, and designers say it could be scaled to produce X-ray light.

"This is a radical new design that can be used to create light sources that are more compact than can be achieved using a conventional undulator," said Sami Tantawi, a SLAC particle physics and astrophysics professor who led the development effort.

The microwave undulator can produce shorter wavelengths of light – using less driving energy from electrons than conventional undulators. This means the accelerator that feeds it electrons can shrink considerably, Tantawi said.

A Step Toward Tabletop X-ray Lasers

"This brings us much closer to the dream of a tabletop X-ray free-electron laser," Tantawi said. "We have proved, in principle, that this is possible."

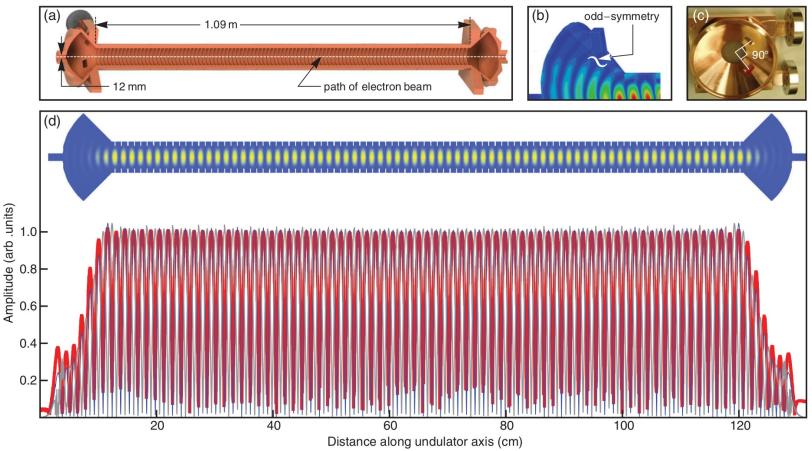

Electrons beamed into the undulator encounter rapidly alternating high-power microwave fields that cause the electrons to wiggle, emitting light at specific wavelengths. The wavelength and other properties of this light can be precisely tuned to suit many different types of experiments by adjusting the energy of the electrons and the microwave power.

Tantawi said, "Because it doesn't have any moving parts, the microwave undulator is amenable to scaling down to very short wavelengths." Increasing its length and supplying more electron energy could allow it to produce X-ray pulses like those generated by the LCLS X-ray laser. Its scalability and rapid tuning sets it apart from other next-generation undulators, he noted.

A Next-generation Source of Highly Tunable Light

The new device, featured on the cover of the April 25 edition of Physical Review Letters, could be used to provide more highly tailored light pulses that open new realms of experimental possibilities, particularly for studies of materials with exotic properties. It could be incorporated into next-generation lasers, synchrotrons and particle colliders and installed in existing facilities, such as SLAC’s LCLS and SSRL.

Also, Tantawi said he would like to pursue a superconducting version of the undulator that would require supercooling in order to produce a more continuous stream of light for experiments.

"This technology has vast potential to dynamically control the properties of the light for use in many scientific experiments," Muhammad Shumail, a PhD student who is writing his thesis about the undulator, said.

With further miniaturization, it is conceivable that the microwave undulator could serve as a portable medical imaging source, Tantawi said. "The next step of the research is to really make this technology more available."

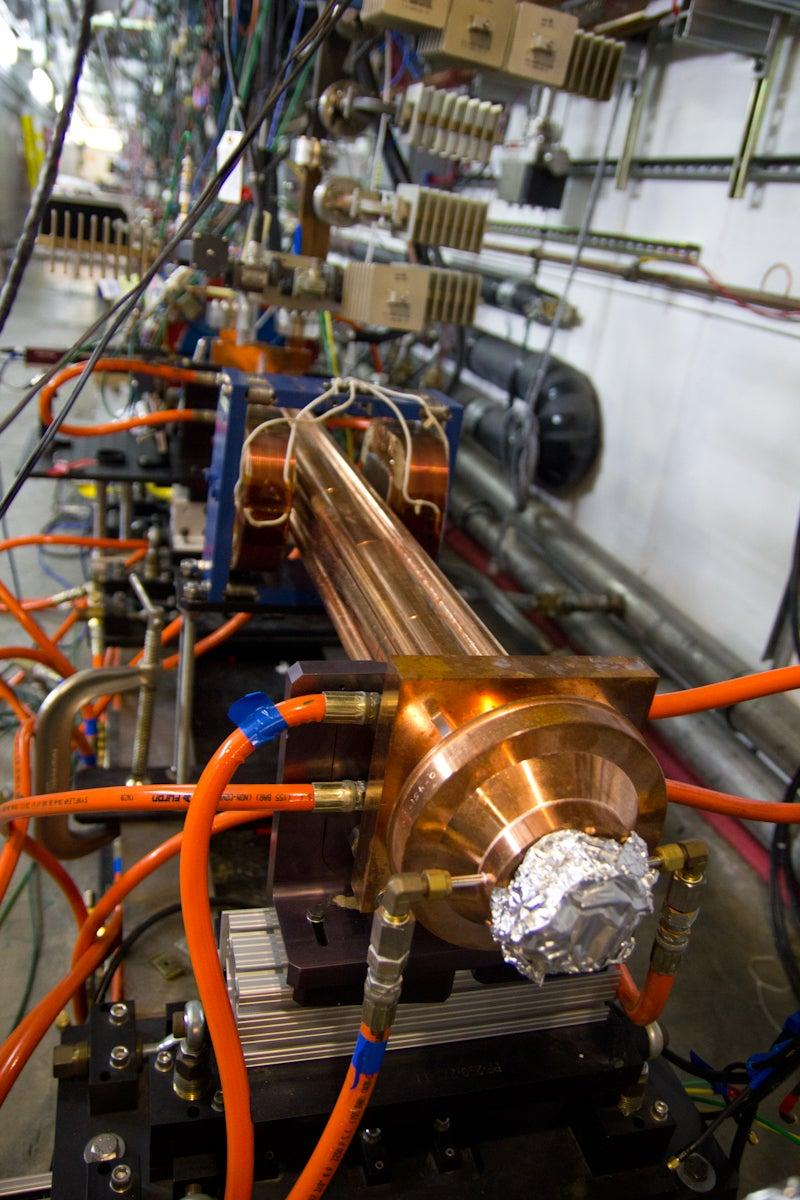

SLAC technologist Gordon Bowden said building the prototype device was challenging, requiring specialized tools to cut a series of tiny ribs from the inside of the copper pipe the undulator is made of. The ends of the device had to be precisely tapered to better trap the microwave energy in the device.

"No conventional undulator has the agility that this device can offer," Bowden said. "The unique properties of the light that emerges from the undulator are due to the precise comb-like pattern of the microwave fields trapped inside," he said.

Unique Expertise

Tantawi said SLAC’s historic and unique expertise in accelerators and microwave technology was well-suited to the development of the new device. "This is one of the few places on the planet we could have built this," he said. The first magnetic undulator was built by Stanford researchers in the 1950s.

The pursuit of the microwave undulator was inspired by Tantawi's conversations with X-ray free-electron laser pioneer Claudio Pellegrini and by Joachim Stöhr, SLAC photon science professor, and the design stemmed from his work on a similar design for an antenna that could be used to explore the so-called cosmic microwave background radiation, which is believed to hold clues to the earliest origins of the universe.

Also participating in the microwave undulator project: Jeffrey Neilson, Chao Chang, Erik Hemsing and Michael Dunning. The project was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency AXiS program.

Citation: Sami Tantawi, Muhammad Shumail et al., Physical Review Letters 112, 164802 (2014), DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.164802.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.