Scientists Line Up Unruly Gas Molecules for X-rays

A study with SLAC's X-ray laser is a key step toward producing movies that show how a single molecule changes during a chemical reaction

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

It's hard to study individual molecules in a gas because they tumble around chaotically and never sit still. Researchers at SLAC overcame this challenge by using a laser to point them in the same general direction, like compass needles responding to a magnet, so they could be more easily studied with an X-ray laser.

The experiment with SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), reported Dec. 6 in Physical Review A, is a key step toward producing movies that show how a single molecule changes during a chemical reaction. Understanding the many stages of a reaction could help scientists design more efficient, controllable reactions for important industrial processes, many of which rely on gases that react with solids.

"This is the 'trailer' for the molecular movie – these are the first frames," said Daniel Rolles of the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science at DESY national laboratory in Germany, who led the experiment. "People know, theoretically, that molecules do all kinds of weird things. If you can see the changes and check the theory, then you can understand how it's happening and have a handle on controlling it."

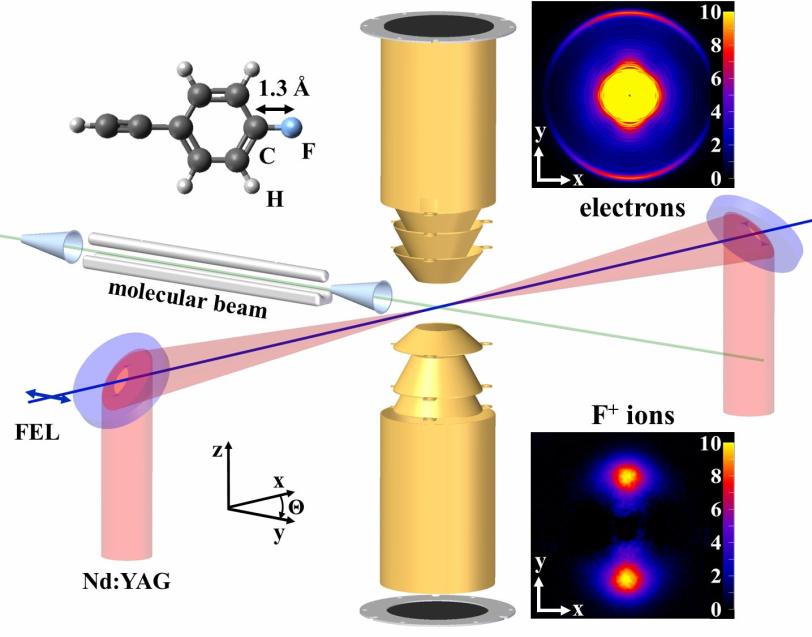

In the experiment, researchers jetted a thin stream of fluorocarbon gas into the path of two intersecting lasers: an optical laser that polarized the molecules – aligning them along a common axis, like a spinning top with a slight wobble – and the LCLS X-ray laser.

Fluorocarbon molecules were chosen because their chemical makeup allows them to be polarized by the electric field of a laser and because they are somewhat complex; each features a ringed structure and a tail-like spur and contains more than a dozen atoms. This makes them a good test case for future studies of even larger molecules.

The X-ray laser was carefully tuned so it would eject electrons mostly from the fluorine atoms in the sample before bursting the molecules into charged fragments. Scientists measured the freed fluorine electrons and charged fluorine fragments with sensitive detectors, and sorted and analyzed this data to reconstruct the original shape and structure of the molecules. Even though each X-ray laser pulse hit many molecules, the angles of the ejected electrons revealed details about the structure of individual molecules.

The LCLS X-ray laser is uniquely suited for this type of atomic-scale chemical study because it allows scientists to pinpoint a particular element in a molecule that they want to study, Rolles said.

"This is element and site specific: We can pick one place in a molecule and image that environment," he said." It's like singling out one type of tree that otherwise would be hidden by the forest around it." That selectivity can allow scientists to zero in on areas of particular interest in a chemical reaction.

Laser alignment of molecules, first demonstrated in 1999, is still a very young field, and the ultrafast X-ray pulses from the LCLS could allow scientists to study changes in aligned molecules that occur in quadrillionths of a second – a far shorter timescale than possible with other research tools. While not all molecules can be aligned with lasers, the researchers note that a rich assortment of molecules is suited to the technique.

If researchers could achieve fuller, three-dimensional alignment of molecules – like stopping a spinning top with your finger and rotating it to face you in a certain way – they would have an even easier time measuring their properties and determining their structure. "You could solve the structure of an individual molecule even without prior knowledge of its shape," said John Bozek, an LCLS staff scientist who participated in the experiment, adding that this could be useful for studying the intermediate stages of a chemical reaction.

Rolles said his team is working on new techniques for aligning and imaging molecules, with a goal of studying larger molecules with more exotic structures.

Collaborators included researchers from SLAC; the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science in Germany; Max Planck institutes for nuclear physics, structural dynamics, medical research and biophysical chemistry in Germany; German national lab DESY; Aarhus University in Denmark; Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics in India; University of Trieste in Italy; Göttingen and Hamburg universities in Germany; Max Born Institute in Germany; FOM-Institute AMOLF in The Netherlands; the Physical-Technical Federal Institute (PTB) in Germany; and Kansas State University.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.