X-ray Laser Sees Photosynthesis in Action

Menlo Park, Calif. — Opening a new window on the way plants generate the oxygen we breathe, researchers used an X-ray laser at the Department of Energy’s (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory to simultaneously look at the structure and chemical behavior of a natural catalyst involved in photosynthesis for the first time.

Menlo Park, Calif. — Opening a new window on the way plants generate the oxygen we breathe, researchers used an X-ray laser at the Department of Energy’s (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory to simultaneously look at the structure and chemical behavior of a natural catalyst involved in photosynthesis for the first time.

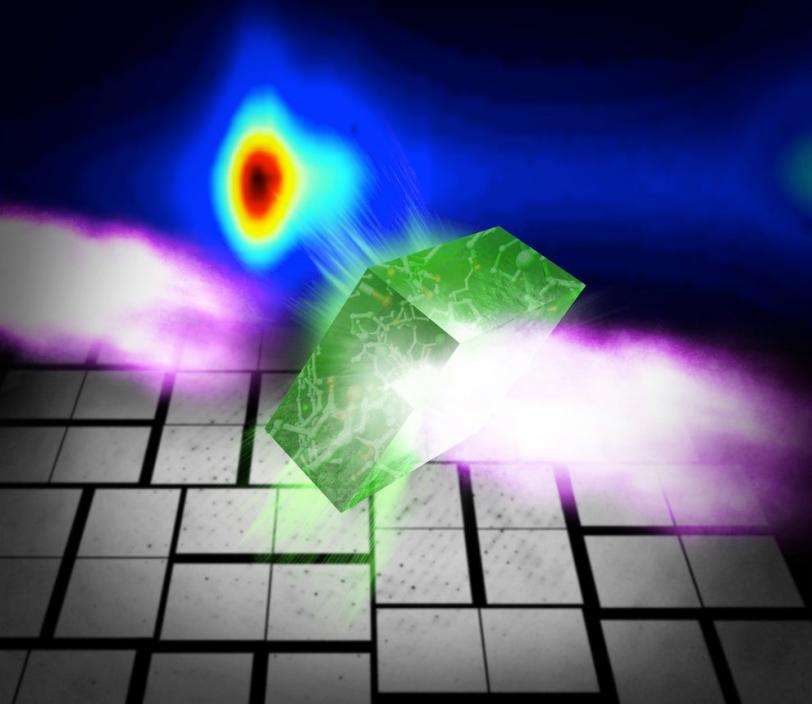

The work, made possible by the ultrafast, ultrabright X-ray pulses at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), is a breakthrough in studying atomic-scale transformations in photosynthesis and other biological and industrial processes that depend on catalysts, which efficiently speed up reactions. The research is detailed in a Feb. 14 paper in Science.

“All life that depends on oxygen is dependent on photosynthesis,” said Junko Yano, a Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory chemist and co-leader in the experiment. “If you can learn to do this as nature does it, you can apply the design principles to artificial systems, such as the creation of renewable energy sources. This is opening up the way to really learn a lot about changes going on in the catalytic cycle.”

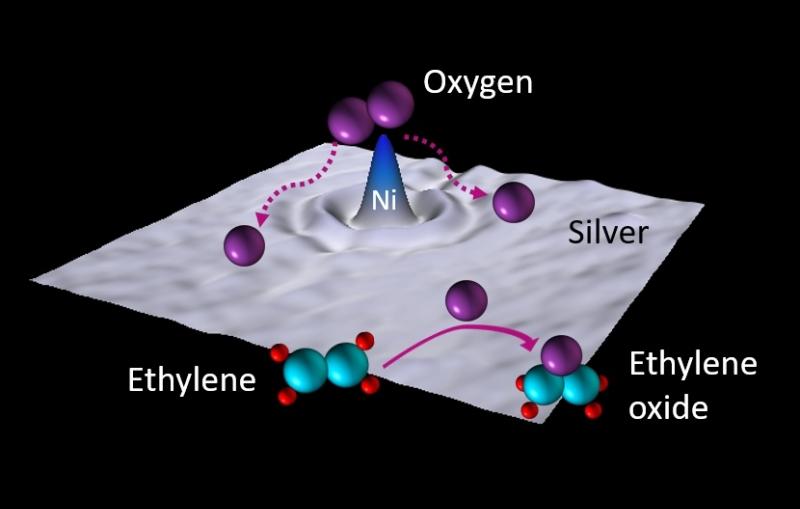

Catalysts are vital to many industrial processes, such as the production of fuels, food, pharmaceuticals and fertilizers, and represent a $12 billion-per-year market in the United States alone. Natural catalysts are also key to the chemistry of life; a major goal of X-ray science is to learn how they function in photosynthesis, which produces energy and oxygen from sunlight and water.

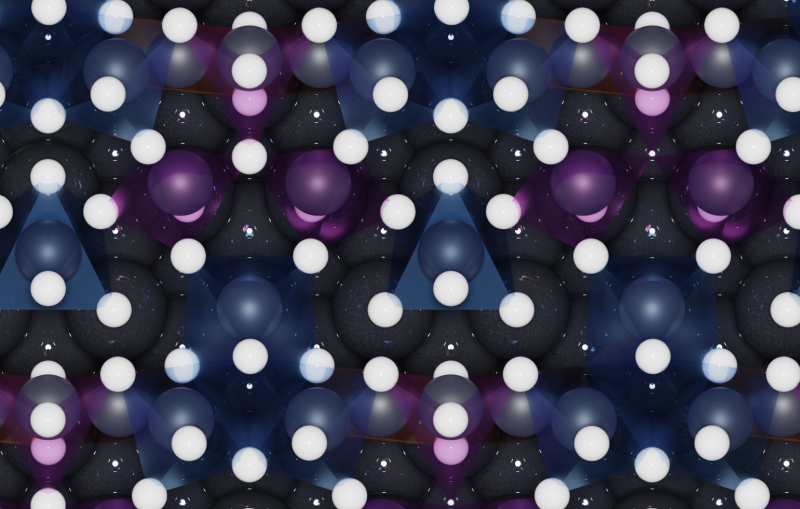

The LCLS experiment focused on Photosystem II, a protein complex in plants, algae and some microbes that carries out the oxygen-producing stage of photosynthesis. This four-step process takes place in a simple catalyst – a cluster of calcium and manganese atoms. In each step, Photosystem II absorbs a photon of sunlight and releases a proton and an electron, which provide the energy to link two water molecules, break them apart and release an oxygen molecule.

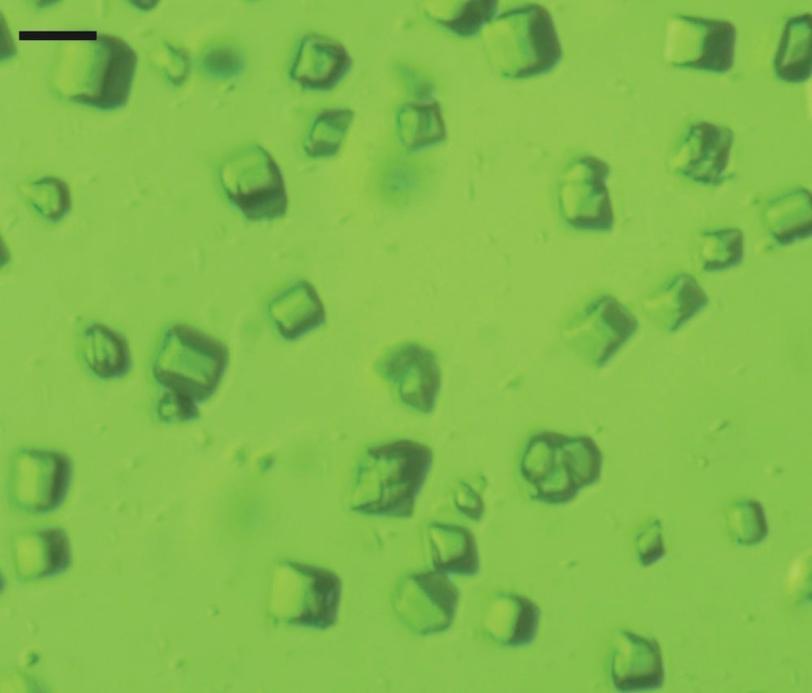

Past studies were able to freeze crystals of the catalyst at various stages of the process and see how it looked. But scientists wanted to see the chemistry take place. This was not possible at other X-ray facilities, because the fragile crystals had to be frozen to protect them from radiation damage.

However, the LCLS X-ray laser comes in such brief pulses – measured in quadrillionths of a second – that they could probe the crystals at room temperature in a chemically active state, before any damage set in, and generate data on two of the four steps in oxygen generation.

“We decided to use two X-ray techniques at once at the LCLS: crystallography to look at the overall atomic structure of Photosystem II, and spectroscopy to document the position and flow of electrons in the catalyst,” said Vittal Yachandra, a Berkeley Lab chemist and co-leader of the project. “The electrons are important because they are involved in making and breaking bonds and other processes at the heart of chemical reactions.”

Another co-leader, SLAC physicist Uwe Bergmann, said, “This result is a critical step in the ultimate goal to watch the full cycle of the splitting of water into oxygen during photosynthesis.” The use of both techniques also verified that the molecular structure of the samples is not damaged during measurement with the LCLS, he said. “It’s the first time that we have resolved the structure of Photosystem II under conditions in which we know for sure that the machinery that does the water splitting is fully intact.”

In future LCLS experiments, the researchers hope to study all the steps carried out by Photosystem II in higher resolution, revealing the full transformation of water molecules into oxygen molecules – considered a key to unlocking the system’s potential use in making alternative fuels.

“Getting a few of the critical snapshots of this transition would be the final goal,” said Jan Kern, a chemist who holds a joint position at Berkeley Lab and SLAC and is the first author of the paper. “It would really answer all of the questions we have at the moment about how this mechanism works.”

Besides scientists from Berkeley Lab, SLAC and Stanford University, researchers from Technical University Berlin in Germany, Umea and Stockholm universities in Sweden and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France also participated in the research. This work was supported by the DOE’s Office of Science, the National Institutes of Health, the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Alexander von Humbolt Foundation, Umea University, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and the Swedish Energy Agency.

LCLS is supported by DOE’s Office of Science. SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit www.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Citation

J. Kern et al., Science, 14 Feb 2013 (10.1126/science.1234273)

Press Office Contact

Andy Freeberg, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory: afreeberg@slac.stanford.edu, (650) 926-4359

Scientist Contact

Uwe Bergmann, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory: bergmann@slac.stanford.edu