SSRL Yields Clues to Function of Vital Protein Family

A team of Stanford University researchers used the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource to gain a deeper understanding of a vital family of signaling proteins responsible for regulating an organism’s development and growth, as well as tissue regeneration and wound healing.

By Lori Ann White

A team of Stanford University researchers used the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource to gain a deeper understanding of a vital family of signaling proteins responsible for regulating an organism’s development and growth, as well as tissue regeneration and wound healing. The protein family, known by the collective name “Wnt,” can cause havoc when their signals go astray; mistakes in Wnt signaling are associated with the development of many types of cancer, including colon cancer, breast cancer and melanoma, and degenerative diseases like multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's and type 2 diabetes.

Understanding how Wnt proteins bind to and activate their receptors could lead to the development of effective drugs for the treatment of Wnt-related diseases.

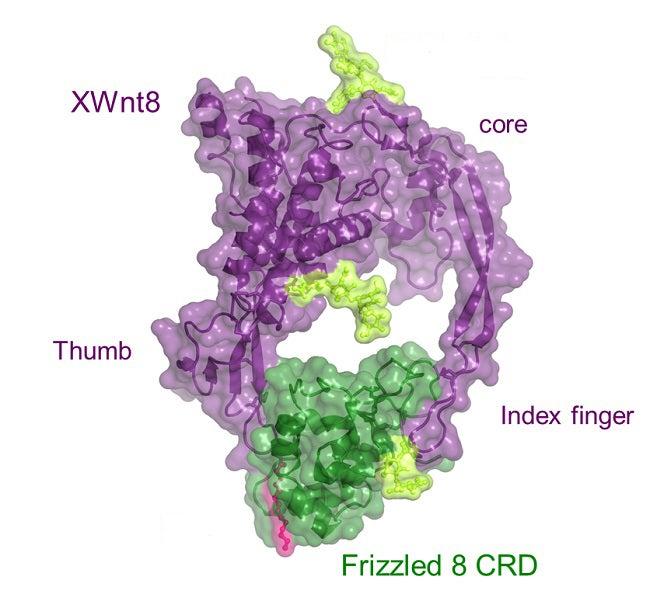

A major target of Wnt proteins is a group of receptors with the evocative name “Frizzled” that are located on the surfaces of cells. Frizzled receptors are members of the larger family of G-protein-coupled receptors; research into these complex, cell-wall-spanning receptors recently garnered the 2012 Nobel Prize in chemistry for Stanford’s Brian Kobilka. Now another Stanford team, led by Christopher Garcia of the School of Medicine, has used a technique called X-ray crystallography at SSRL to create the first 3-D image of a Wnt protein locked to a Frizzled complex, in the process overcoming challenges posed by the reluctance of the lipid-rich Wnt proteins to freeze into crystals of a high-enough quality to examine.

The researchers discovered that the structure of this particular Wnt protein resembles a fist with outstretched thumb and index finger, “an unusual two-domain Wnt structure, not obviously related to known protein folds,” as noted in the resulting paper. The two digits pinch the roughly globe-shaped Frizzled receptor complex on opposite sides. A lipid attached to the Wnt thumb-tip binds to a long, deep groove in the Frizzled complex, while the tip of the Wnt index finger binds to a wide and shallow groove in the opposite side of the complex, mediating Wnt/Frizzled-specific interactions.

Their results appeared in a recent issue of Science.