LCLS Finding May Lead to Better Models of Matter Under Extreme Conditions

Any nanometer-sized sample exposed to the intense X-ray pulses of SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source is quickly ionized – stripped of electrons – and soon explodes.

By Diane Rezendes Khirallah

Any nanometer-sized sample exposed to the intense X-ray pulses of SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source is quickly ionized – stripped of electrons – and soon explodes. The trick is to collect information on the sample before the damage from the X-rays sets in, a technique known as “diffract before destroy.”

In a report in Physical Review Letters last week, a team led by SLAC Ph.D. candidate Sebastian Schorb found that the damage process in nanometer-sized clusters of atoms is slower than expected from previous studies of atoms and simple molecules.

The results suggest that there may be a slightly longer window, in particles of this size, for collecting the data used to make images before significant damage sets in.

“In simple terms, the speed of the ionization process triggered by the intense X-ray pulse depended on the sample size,” Schorb said. “This is an important finding for people trying to find the optimal way to tune the beam for imaging nanoscale structures.”

The team conducted its experiments with the LCLS’s Atomic Molecular Optical instrument in October 2010. Using a slotted spoiler – a piece of foil with a slit in it – they were able to control the pulse length within a few tens of femtoseconds. They hit clusters of argon atoms with those precisely tuned X-ray pulses and observed what happened as the clusters absorbed the energy of the beam.

When a laser pulse hits a sample, photons of X-ray light strip away electrons from the innermost shells of the sample’s atoms. In a process known as Auger decay, other electrons quickly fall in to fill the holes, only to be hit by subsequent photons and ejected in turn. Eventually the sample absorbs so much energy that it turns into a hot plasma and flies apart.

But in the case of the nanoclusters, the Auger decay process was delayed. The cluster itself became a “nanoplasma” of quasi-free, ejected electrons and positively charged ions, confined in a small space. And within this nanoplasma, it took just a little longer than predicted for outer electrons to fall in and fill holes in atoms’ inner shells. During the brief time the holes remained open, the atom was essentially “transparent” to further damage from the laser beam, because it had no electrons in position to be stripped away.

The researchers chose argon for its simplicity and because it produces clusters reliably, but Schorb points out they could have chosen another element. “The argon itself wasn’t important,” he said. “The point of the research was to use clusters as a model to understand fundamental processes that happen in all nanometer-size samples.”

Schorb said the results offer a better understanding of light-matter interaction using LCLS with nanometer-size objects. It could help develop more sophisticated models for studies of matter in extreme conditions.

“Later on, people can make use of it to do further work,” Schorb said. “It may have an impact on people looking at damage models.”

Researchers expect the results to prove useful to a wide range of experiments, from studying the dynamics of dense plasmas to working with damage models.

The team’s experiments were part of an in-house research program at SLAC where a certain fraction of beam time is made available for internal use on a competitive basis. Schorb expects to complete his Ph.D. in the next three months; this work is the subject of his thesis.

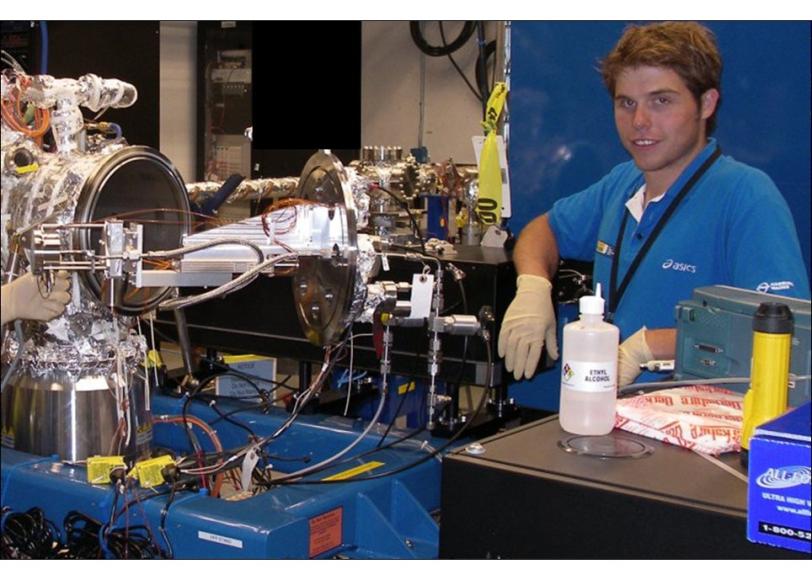

His advisor, LCLS instrument scientist Christoph Bostedt, says Schorb was critical in getting the AMO instrument commissioned in late 2010, and was later involved in many user runs at AMO. Starting as a student on a travel grant and then working as an AMO student team member, “he helped anywhere from tightening flanges to commissioning and redesigning detectors.

"The users greatly appreciated him, and often asked specifically for him to join their experiments,” Bostedt said. “He is a very talented physicist who makes himself useful wherever there is a need.”

(Photo by Jack Pines)