Fifth X-ray Instrument at LCLS Debuts, With a Bead on Disorderly Structures

After five night shifts of shooting pairs of X-ray pulses through soups of fine sand and gold, Aymeric Robert was tired but exhilarated. The first experiment with an instrument he helped bring into being – the X-ray Correlation Spectroscopy (XCS) instrument at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source – had just ended, launching a new tool for understanding liquids, glasses and other less-than-orderly substances.

By Glennda Chui

After five night shifts of shooting pairs of X-ray pulses through soups of fine sand and gold, Aymeric Robert was tired but exhilarated. The first experiment with an instrument he helped bring into being – the X-ray Correlation Spectroscopy (XCS) instrument at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source – had just ended, launching a new tool for understanding liquids, glasses and other less-than-orderly substances.

“I think it went great – but gosh, it was challenging,” said Robert, who as instrument scientist for the XCS had spent more than five years overseeing its design, construction, commissioning and operation. “This is going to open up new classes of experiments, once it’s up and running and well understood. But these experiments are extremely challenging.”

The XCS is the fifth of six planned instruments to open for business at the LCLS, and like its predecessors, it has a highly specialized niche: Revealing changes over time, technically known as dynamics, in materials such as glasses, gels and polymers that lack a regular atomic structure. Understanding those changes on an atomic level will help researchers create new materials with better properties for a wide variety of uses.

The principle behind the XCS is called Photon Correlation Spectroscopy, and it works like this: Researchers hit a sample of material with pulses of laser light, creating grainy “speckle patterns” that can be compared to see how the structure of the sample changed between hits. (See the XCS home page for images, videos and more.)

The technique has been used for years to probe materials with visible-light lasers, and more recently with X-ray light from synchrotrons. But the LCLS is the first machine to provide ultra-short pulses of laser light at short, “hard” X-ray wavelengths, which can penetrate deeper into samples, reveal features down to the size of atoms and, most importantly, capture much faster changes.

“The concept of these XCS experiments is fundamentally different from that used at the other instruments,” said Uwe Bergmann, deputy associate lab director for the LCLS. “By hitting samples with carefully tuned pairs of laser pulses, we’ll be able to see subtle changes that naturally occur in these materials over very fast time scales. XCS will entirely open up, and have a tremendous impact on, the study of disordered systems.”

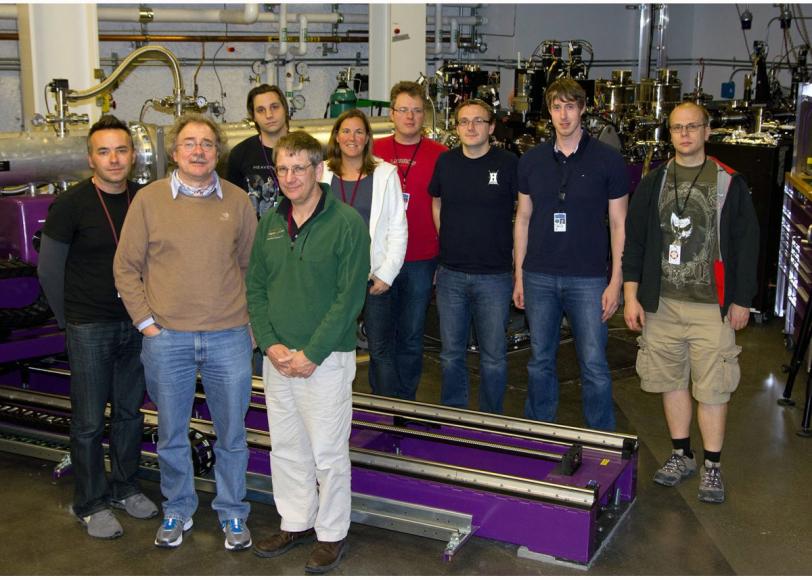

In addition to Robert, members of the instrument team that support and run the XCS are Marcin Sikorski, Venkat Srinivasan, Robin Curtis, Daniel Flath and Sooheyong Lee.

Two ways to operate

In its basic mode, the XCS will measure changes taking place on timescales ranging from 10 thousandths of a second to thousands of seconds.

But scientists can also use a new optical device, called a split-and-delay unit, to capture much faster changes. The device uses eight perfect crystals to split each laser pulse in two and send the members of each pair down different paths, one slightly longer than the other. When the pairs of pulses meet up again in a single beam and hit the sample, they’re less than 3 billionths of a second apart – and sometimes separated by as little as a few millionths of a billionth of a second. The resulting speckle patterns reveal subtle changes that naturally take place in the sample on this very short timescale.

These dynamical changes occur in all sorts of things, from biological molecules to crystalline and glassy materials, and studying them is one of the chief things the LCLS was built to do. A big advantage of the split-and-delay unit is that it lets scientists adjust the time between pulses and even their relative intensities to achieve different effects.

Split-and-delay can also be used in a different mode: Make the first pulse strong enough to deliberately trigger changes in the sample, and then measure those changes with the second pulse. This mode of operation is known as pump-probe.

XCS science begins

The first experiment with the XCS got under way on Thanksgiving night. Robert and the rest of the experimental team spent the first part of the five-day run aligning the two halves of the beam and measuring their characteristics as they traveled 12 meters down the Far Experimental Hall.

Then they ran tests on prototype samples – liquids containing nanoparticles of gold or silica.

At the regular 8 a.m. Monday briefing for LCLS scientists, principal investigator Gerhard Grübel displayed their first speckle pattern, achieved near the end of an overnight run, at 7:32 on Sunday morning.

“It’s actually a lot of fun being the first one on a new beamline,” he said, smiling broadly. He thanked the accelerator operators for providing such a steady stream of laser pulses. “The beam was always there,” Grübel said. “It’s a remarkable experience to use such a reliable machine.”

The experiment brought together several of the key people involved in the development of the XCS.

Grübel, a senior scientist at the German national laboratory DESY, was among a group of researchers who initially proposed that the LCLS include an instrument of this kind. He also led the development of the first X-ray photon correlation spectroscopy instrument, called Troika, at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France.

Robert had worked with Troika for nine years as a doctoral student, postdoctoral researcher and, finally, beamline scientist before joining the LCLS as an instrument scientist and guiding the construction of the XCS, which is roughly as long as two football fields, from start to finish.

G. Brian Stephenson of Argonne National Laboratory hosts a storage ring-based XCS beamline at the Advanced Photon Source, which he directs.

And Wojciech Roseker, now a postdoctoral researcher at DESY, developed the split-and-delay device during his PhD studies there. It was tested there and at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, and then brought to SLAC for installation.

Future experiments

Grübel said he hopes to apply the XCS to the study of molecular fluids, in particular to water – the most common and ordinary liquid on Earth, essential to life and yet barely understood. Studies over the past decade have shown that this seemingly random fluid can contain patches of ordered water molecules. Researchers are still exploring the boundaries between its phases – the specific conditions of temperature and pressure at which water freezes or evaporates.

But for the time being, experiments with the split-and-delay device will be aimed at understanding how it works and getting it to run so smoothly and seamlessly that it’s essentially a “black box,” as Robert puts it, that scientists can routinely operate without any special expertise.

The XCS can also be applied to other materials that lack a regular order – such as glasses, which seem to be solid but are actually more like liquid, imperceptibly flowing. Even within seemingly stolid solids, atoms shift places. Upcoming XCS experiments will explore the dynamics of glasses, gels and polymers. Disordered though they may be, they’re rich in scientific and practical potential. Now the XCS will give researchers a whole new way to plumb it.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

(Photo by Kelen Tuttle)