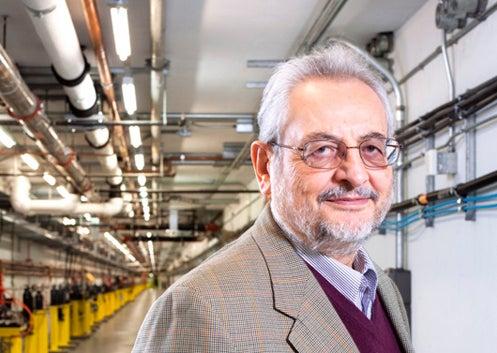

Claudio Pellegrini: A Patriarch of the LCLS

"It takes a village," as Hillary Clinton famously wrote, "to raise a child."

By Lori Ann White

"It takes a village," as Hillary Clinton famously wrote, "to raise a child." Similarly, says physicist Claudio Pellegrini, it takes an entire scientific community to create a ground-breaking new piece of technology—one that not only adds to the store of human knowledge through its use, but requires its designers to push back scientific and technological frontiers just to build it in the first place. The Linac Coherent Light Source is a case in point.

The LCLS is a half-billion-dollar free-electron laser, or FEL, which has given new purpose to SLAC's fifty-year-old linear accelerator and new tools to researchers seeking to better understand the natural world. For the first time the LCLS enables direct study of phenomena on the smallest and fastest scales imaginable—as small as atoms and as fast as an electron circles around an atomic nucleus. As an FEL, the LCLS uses an electron beam to generate extremely bright, intense, coherent X-rays—much like a laser does for visible light—which can be used to image biological materials such as individual viruses or proteins at work, study ultrafast changes in the electronic configurations of high-performance materials, and watch what happens to matter when it's put under extreme temperatures and pressures.

Just as every child has to start somewhere, every piece of cutting-edge equipment needs someone to see past the edge in the first place. In the case of the LCLS, that someone was Pellegrini, who, in 1992, first proposed that the SLAC linac be put to such a novel use.

"I feel like the father," Pellegrini admitted with a laugh. But as Pellegrini himself is quick to point out, the history of the LCLS extends even farther back than his 1992 proposal, and is closely intertwined with Pellegrini's own history at SLAC, which stretches back nearly to the lab's inception.

"I can't believe the first time I was here was in 1965," Pellegrini said. "Pre-history." In 1965, Pellegrini was a young Italian physicist with INFN, the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare. Particle colliders were the next big thing in high-energy physics, and Pellegrini was at INFN's laboratory in Frascati, near Rome, working on ADONE, INFN's high-powered electron–positron collider.

"I was at Frascati, and we were designing and building ADONE, and here at SLAC [Burton] Richter, [Matt] Sands and others were working on the design of SPEAR as an electron–positron collider," Pellegrini explained. "Particle colliders were all new. There were people in the U.S., people in Europe, trying to see how they could be developed. There was a lot of exchange." Pellegrini came to a two-week workshop held at SLAC as part of that international exchange of ideas. "That was a very exciting workshop, really. There was a lot of work to be done and new phenomena to explain, so it was fun, and we really had time to make progress in many areas."

Pellegrini made regular visits to the area, spending two tumultuous years at Berkeley in 1969 and '70, working with [Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Director Emeritus Andrew] Sessler ("I have movies of all the riots. Peoples' Park. It was very exciting."), then again at SLAC for three months in 1976—"apart from all the workshops and that kind of stuff."

Something happened in 1976 that changed the course of Pellegrini's career. Stanford University physicist John Madey built the first FEL following on work done at Stanford as early as the 1950s by Hans Motz and other scientists on undulator radiation, and on the development of linear accelerators.

"It was a small free-electron laser working in the infrared—10 micron wavelengths," Pellegrini said. "But the fact that it worked generated a lot of interest." Pellegrini was one of the interested parties. "I changed from electron–positron colliders, which by now were working and producing great results, to free-electron lasers."

According to Pellegrini, research on this new type of laser split into two camps—one camp, led by Madey, worked on producing high average power infrared FELs with high average power for the Star Wars defense program. Pellegrini was more interested in pushing the FEL to produce coherent X-rays. In 1984 he and two colleagues published a theoretical paper describing the properties of a process called "Self-Amplified Spontaneous Emission," or SASE, in which an electron beam with the proper characteristics spontaneously emits coherent X-rays. He continued with theoretical and experimental efforts to show that the SASE process made possible X-ray wavelengths as short as one angstrom, or one ten-billionth of a meter. The experimental work was carried out initially at UCLA, and later at Los Alamos and Brookhaven, in a collaboration involving UCLA, Los Alamos National Laboratory, SLAC and Brookhaven National Laboratory.

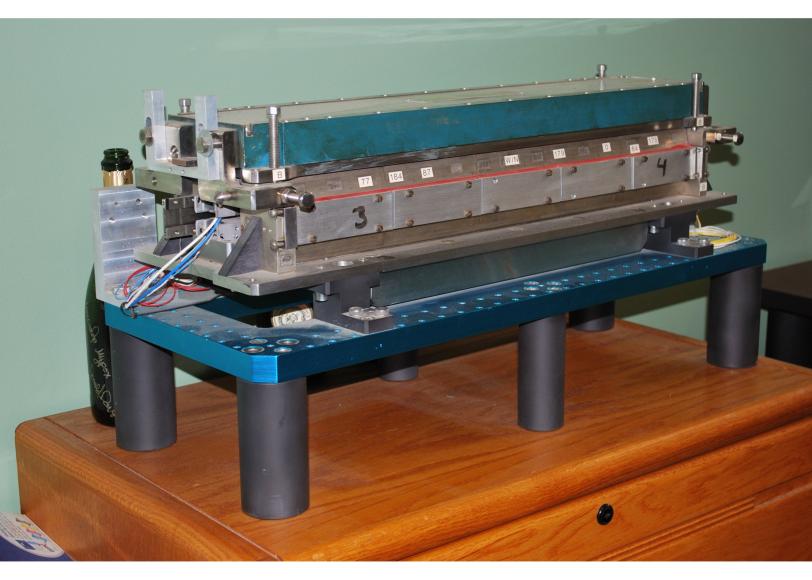

Pellegrini considers the 1984 paper to be the real start of his involvement in what was to become, 25 years later, the LCLS. Many colleagues from the accelerator physics community joined him in overcoming the technical challenges. The effort gained momentum after that fateful workshop in 1992 where Pellegrini first proposed the LCLS. His account is a laundry list of contributions made by a phone book's worth of collaborators, from a vital piece called a photoinjector that was developed at Los Alamos National Laboratory "by Sheffield and Fraser," to inexpensive Chinese wave guides and radio-frequency components Pellegrini used to create an FEL prototype on a tight budget, to a free undulator magnet "built by Varfolomeev’s group in Russia," that Pellegrini used at to experimentally demonstrate SASE.

"It's in my office now. It's 60 centimeters long. That's small, but very, very nice."

According to Pellegrini, how to accelerate an electron beam while preserving the high beam quality necessary to generate coherent X-rays was an important contribution from high energy physics in general and the linear collider experience here at SLAC in particular. SLAC people played another important role, as well.

”Most people in the FEL community believed an X-ray FEL would never work, and they were not totally crazy," Pellegrini said. "There were a lot of reasons—everything had to be done at the frontier, pushing the knowledge and with extreme technical quality. And it was not an easy job. It was very good that a few people here, like Herman Winick, Artie Bienenstock and Max Cornacchia, believed in this idea and started to support it."

Pellegrini's determined band of physicists finally caught the attention of the Department of Energy, which decided to fund the project. "And you know the rest of the story," he said—the successful launch of the world's first hard X-ray FEL in 2009.

"In a way, the final success that came so brilliantly in 2009 was a demonstration of how much the accelerator physics community had done. Building the LCLS was such a difficult task—at the frontier of what man could do—bringing together new developments in linear colliders, the photoinjector, instrumentation, diagnostics, theory and simulations. But it was done by the LCLS team with remarkable success, a demonstration of the quality and the commitment of their work and that of the general community of accelerator physicists. Everybody deserves much recognition for the final success."

Pellegrini retired last year from UCLA and now works at SLAC. "At this point in my life I work part-time," he said. His part-time work involves improvements to future FELs. "At the moment I'm working on some general aspects of these FELs. LCLS is great, but one can do more."

Pellegrini said he would like SLAC to become a world-wide center of FEL research and development. To that end, he's helping to push a proposal to build a facility dedicated to FEL studies at SLAC, an idea that has been endorsed by SLAC's Scientific Policy Committee.

"That's something we really would need to push the free-electron laser to its maximum level of capability. Because LCLS by now is so busy that to take the time on it to test a new idea is very hard," Pellegrini explained.

"This is my point of view," he said. "LCLS is not the arrival point, but a starting point."