since its founding days in the 1960s

researchers at SLAC National Accelerator

Laboratory have been generating beams of

electrons to study some of nature's best

kept secrets in the past scientists use

these beams for powerful particle

collisions that revealed fundamental

building blocks of matter today SLAC

uses is electron accelerators mostly for

the generation of x-rays these are

emitted as the flight path of electrons

is bent my magnets at the Stanford

synchrotron radiation light source

ssrl and at the x-ray laser Linac

Coherent Light Source LCLS one of the

most powerful x-ray sources on earth

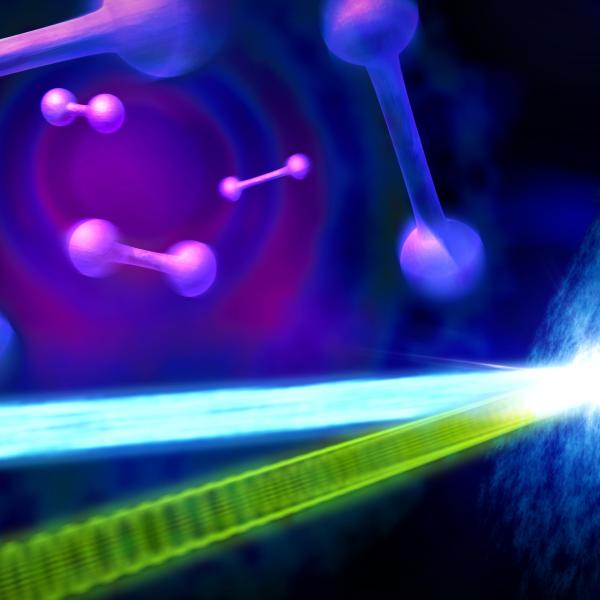

recently SLAC researchers have begun to

explore another way of using electrons

to probe the inside of materials with a

method they call ultra-fast electron

diffraction electrons are generally

viewed as particles yet they also behave

like waves similar to waves of light the

higher the energy of the electron the

shorter its wavelength becomes if the

wavelength is short enough the electron

wave can collect information about the

atomic structure of the object that it

passes through just like x-ray waves

reveal the inside of materials using

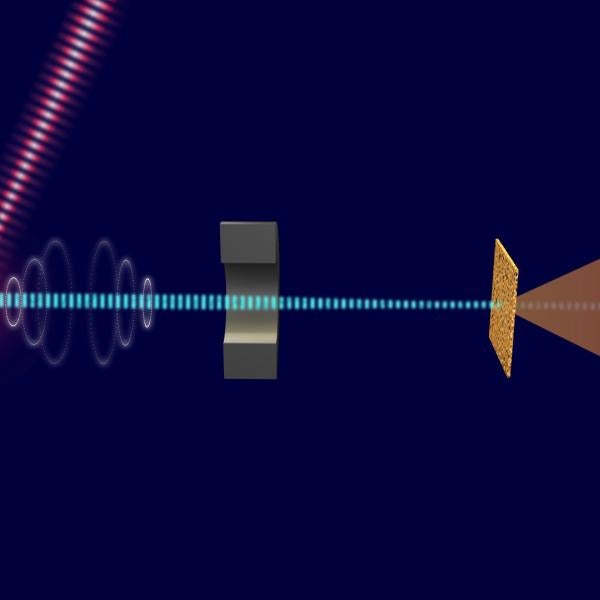

this property of electrons researchers

can build a new set up for ultra-fast

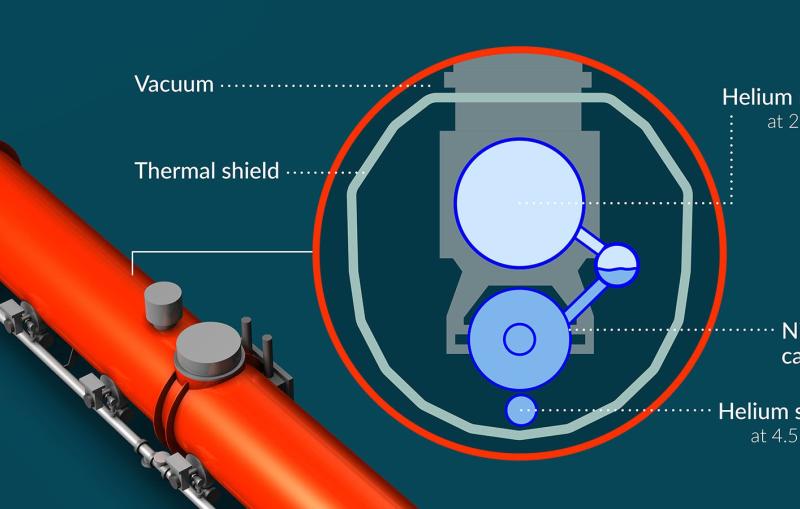

electron diffraction it all starts with

the production of a high-quality beam of

very energetic electrons based on a

technology developed by slack for LCLs

this is done inside an electron gun

where a laser pulse he's a piece of

metal known as the photo cathode and

evaporates electrons from the metal this

incredibly short bunch of electrons is

then accelerated by a radio frequency

field toward the exit of a gun where a

magnet focuses consecutive bunches into

a narrow beam of electrons traveling at

99.3% of the speed of light

researchers then shine this beam through

a sample the incoming electron waves

scatter off the samples atomic nuclei

and electrons producing scattered waves

that combine to form a characteristic

pattern on a detector this process

called electron diffraction allows

scientists to reconstruct the atomic

arrangement in the sample because the

electron beam consists of a train of

very short widely spaced bunches

researchers can also see ultra-fast

changes in a material structure that

occur in less than a trillionth of a

second for instance in response to laser

light this technique is similar to x-ray

diffraction where scientists shine

x-rays through materials however

electron and x-ray waves are sensitive

to different things and therefore

complement each other x-ray scatter off

electrons only and cannot see atomic

nuclei directly electrons on the other

hand are sensitive to both electrons and

nuclei providing additional information

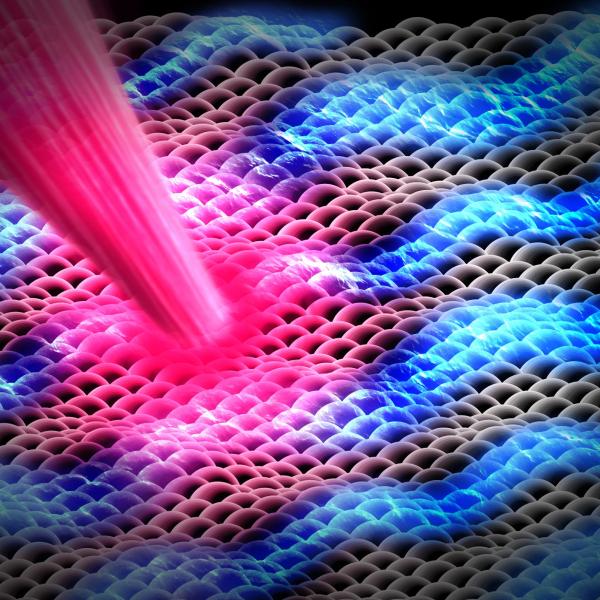

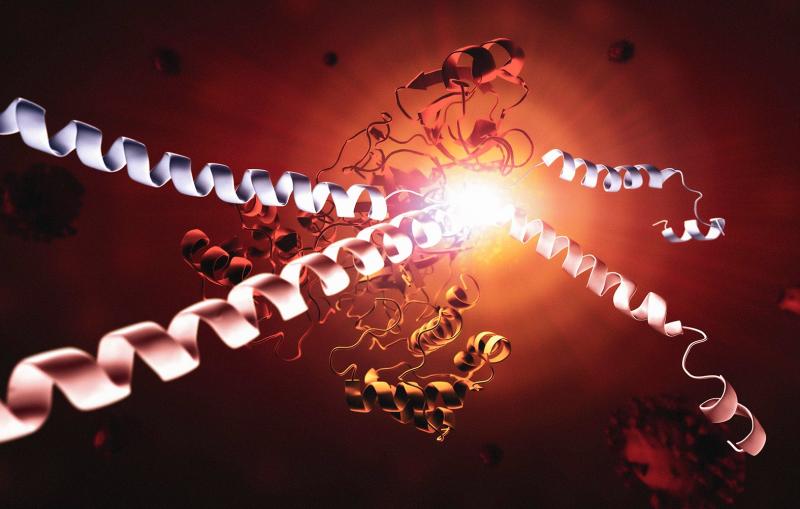

one example where x-ray studies at LCLs

and ultra-fast electron diffraction

experiments go hand-in-hand is magnetic

materials magnetism arises from a

property of electrons known as the

electron spin which is often compared to

a ball spinning on its own axis these

spins float around the materials nuclear

core structure like an electron see but

how does he interplay between the

electrons see and the nuclei impact the

magnetism of the entire material

researchers want to find answers because

a better understanding could help them

build new or better magnetic materials

that could be relevant to data storage

devices and other applications beyond

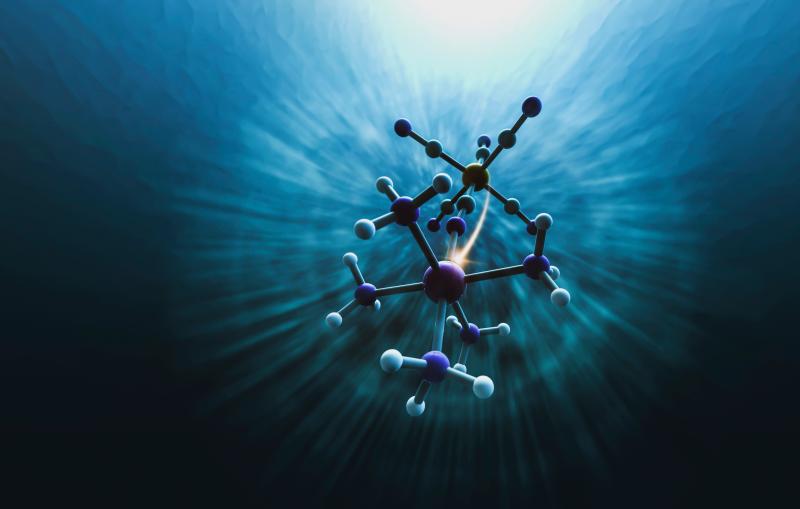

material science researchers also hope

to use a ultra-fast electron diffraction

to record molecular movies and observe

atoms and molecules as they move during

chemical reactions but researchers don't

want to stop there they want to take the

technique to the next level electron

diffraction produces a rather abstract

diffraction pattern so researchers have

to reconstruct how material looks on the

inside

electrons can also be used to take

images of samples directly by inserting

magnetic lenses in front of and behind

the sample the electron diffraction

setup is turned into an electron

microscope similar to his optical

counterpart

however since electrons have a much

shorter wavelength than visible light an

electron microscope can see much finer

details close to the atomic level such

as domains in magnetic materials the

fastest existing electron microscopes

can take snapshots of processes as fast

as 10 billions of a second the slack

researchers hope to improve this time

resolution up to a thousandfold for more

snapshots of the same process in a given

time this would open up new

possibilities for ultra-fast science

you